HISTORY OF THE BARGE CANAL

OF NEW YORK STATE

BY NOBLE E. WHITFORD

CHAPTER VI

THE CANAL CAMPAIGN OF 1903

Contest Transferred to Electorate of State -- Text of Bill -- Special Features: Cost to Be Borne by Whole State: Route Largely River Canalization: Principal Canal Dimensions: Canal Board Governing Body: Governor's Responsibility: State Engineer Directly Responsible: Manner of Making Contracts: Certain Restrictions -- Final Contest On -- Campaign of Education -- Dinner at Buffalo -- Campaign Organizations -- New York City Press -- Canal Literature -- Endorsement by Labor Unions -- Support through Political Parties -- Nature of Opposition -- Sample of Its Literature -- Anti-Canal State Convention -- Letter Issued by Sixteen Senators -- Specimen of Unscrupulous Literature -- Canal Dinner at Utica -- Various meetings -- Public Debates -- School Debates -- Other Meetings -- New York City the Chief Battle Ground -- Reparation for Opposition to Original Canal -- City Organization -- Dinner to Metropolitan Press -- Cart-Tail Campaign -- Mass Meeting at Produce Exchange -- Supreme Court Decision Used by Opposition -- Publication of Letter by Canal Men -- Demonstration of Electric Towage -- Names of Certain Men Responsible for Success of Canal Cause.

The legislative contest of 1903, as we have just seen, was most heated, but the final victory was by no means won with the signature of the Governor. Indeed the campaign had only begun. The two armies simply had transferred their battlefield from the Legislature to the electorate of the whole state.

But before viewing the new engagements of the opposing forces we shall look for a little while at the bill itself, and first we shall transcribe it in its entirety, both because it is an important document and should be read if one is understand the scope and character of the new venture and also in order that it may be at hand for various references we shall have to make to it from time to time. At the end of this transcript we shall speak briefly of some of the outstanding features of the law.

In various publications of this law it has been found useful to print marginal notations consisting of descriptions, expressed in the fewest possible words, of the subject matter of the text. These annotations, which may well be called marginal heading and subheads, are repeated in the present reprint. [noted in this transcription by [bold-face and enclosure in brackets.]] Also at the close of the several sections there are printed, enclosed within parentheses, references to amendments affecting the particular section or pertinent explanatory statements. Sections added by later amendments are given their proper places and what they relate to is briefly stated, but the text is not included. With the exceptions just noted the following copy is the bill which was voted on by the people in 1903, not the law as it has been amended from time to time.

CHAPTER 147, LAWS OF 1903

An act making provision for issuing bonds to the amount of not to exceed one hundred and one million dollars for the improvement of the Erie canal, the Oswego canal and the Champlain canal and providing for a submission of the same to the people to be voted upon at the general election to be held in the year nineteen hundred and three.

Became a law, April 7, 1903, with the approval of the Governor. Passed, three-fifths being present.

The people of the State of New York, represented in Senate and Assembly do enact as follows:

Section 1. [Bonds.] There shall be issued in the manner and at the times hereinafter recited, bonds of the State in amount not to exceed one hundred and one million dollars, which bonds shall be sold by the State, and the proceeds thereof paid into the State treasury and so much thereof as shall be necessary expended for the purpose of improving the Erie canal, the Oswego canal and the Champlain canal, and the procurement of the lands required in connection therewith. [Bonds Exempt.] The said bonds when issued shall be exempt from taxation. (See sec. 1 of chap. 302, Laws of 1906, and sec. 1 of chap. 66, Laws of 1910, Emergency appropriation of $3,654,000, chap. 706, Laws of 1915, Bond issue of $27,000,000, chap 570, Laws of 1915.)

§ 2. [Bond Issue.] The Comptroller is hereby directed under the supervision of the Commissioners of the Canal Fund, to cause to be prepared bonds of this State, to an amount not to exceed one hundred and one million dollars, [Interest.] the said bonds to bear interest at the rate of not to exceed three per centum per annum, which interest shall be payable semi-annually in the city of New York. [Term.] Said bonds shall be issued for a term of not more than eighteen years from their respective dates of issue, and shall not be sold for less than par. [Sale and advertising.] The Comptroller is hereby charged with the duty of selling said bonds to the highest bidder after advertising for a period of twenty consecutive days, Sundays excepted, in at least two daily newspapers printed in the city of New York and one in the city of Albany. Said advertisements shall contain a provision to the effect that the Comptroller in his discretion may reject any or all bids made in pursuance of said advertisements, and in the event of such rejection, the Comptroller is authorized to readvertise for bids in the manner above described as many times as in his judgment may be necessary to effect a satisfactory sale. The said bonds shall not be sold at one time; not more than ten million dollars in amount thereof shall be sold during the two years ensuing after this act takes effect and thereafter they shall be sold in lots not exceeding ten million dollars at a time as the same may be required for the purpose of making partial or final payments on work contracted for in accordance with the provisions of this act, and for other payments lawfully to be made under the provisions hereof. [Tax.] There is hereby imposed for each year after this act goes into effect until all the bonds issued under the authority of this act shall be due, an annual tax of twelve one-thousandths of a mill upon each dollar of valuation of the real and personal property in this state subject to taxation, for each and every one million dollars or part thereof in par value of said bonds issued and outstanding in any of said fiscal years, the annual amount of such tax to be computed by the Comptroller, which taxes shall be assessed, levied, and collected by the annual assessment and collection of taxes of each of such years in the manner prescribed by law and shall be paid by the several county treasurers into the treasury of the State, [Sinking Fund.] and the proceeds of said tax, after paying the interest due upon the outstanding bonds shall be invested by the Comptroller under the direction of the Commissioners of the Canal Fund, and, together with the interest arising therefrom, shall be devoted to the sinking fund which is hereby created, payment from which shall only be made to the extinguishment of the indebtedness created by sale of the aforesaid bonds as the said bonds become due and for no other purpose whatever. (See sec. 2 of chap. 302, Laws of 1906, and chap. 241, Laws of 1901, also sec. 2 of chap. 66, Laws of 1910, and chap. 186, Laws of 1912. Rate of interest on certain bonds 4 1/2 per cent, see chap. 787, Laws of 1913.)

§ 3. [Commencement of work.] Within three months after issuing the said bonds or some part thereof the Superintendent of Public Works and the State Engineer are hereby directed to proceed to improve the Erie canal, the Oswego canal and the Champlain canal in the manner hereinbelow provided. The route of the Erie canal as improved shall be as follows: [Route, Eastern Division, Erie canal.] Beginning at Congress street, Troy, and passing up the Hudson river to Waterford; Thence to the westward through the branch north of Peoble's Island and by a new canal and locks reach the Mohawk river above Cohoes falls; thence in the Mohawk river canalized to Little Falls; thence generally by the existing line of the Erie canal and feeder around through Little Falls to the Mohawk river above the upper dam; thence in the Mohawk river canalized with the necessary cutting through bends to a point just east of Jacksonburg; thence generally by the existing line of the Erie canal to Herkimer; thence in the valley of the Mohawk river following the thread of the stream as much as practicable to a point about six miles east of Rome; [Route, Middle Division, Erie canal.] thence over to and down the valley of Wood creek to Oneida lake; thence through Oneida lake to the Oneida river; thence down the Oneida river cutting out the bends thereof where desirable, to Three River Point; thence up the Seneca river to the outlet of Onondaga lake; thence still up the Seneca river to and through the state ditch at Jack's reefs; thence westerly generally following said river to the mouth of Crusoe creek; thence substantially paralleling the New York Central railroad and to the north of it to a junction with the present Erie canal about one and eight-tenths miles east of Clyde; thence following substantially the present route of the canal with necessary changes near Lyons and Newark to Fairport; thence curving to the south and west on a new location [Route, Western Division, Erie canal.] joining the present canal about one-half mile west of the crossing of the Irondequoit creek; thence following the old canal to a point about one and one-fourth miles west of Pittsford; thence following the existing line of the canal for nearly a mile; thence running across the country south of Rochester to the Genesee river near South Park; here crossing the river in a pool formed by a dam; thence running to the west of the outskirts of Rochester and joining the present canal about one mile east of South Greece; thence following substantially the route of the present Erie canal with the necessary change in alignment near Medina to a junction with the Niagara river at Tonawanda, thence by the Niagara river and Black Rock harbor to Buffalo and Lake Erie. The existing Erie canal from Tonawanda creek to Main street, Buffalo, shall be retained for feeder and harbor purposes. The route of the Oswego canal as improved shall be as follows: [Route, Oswego canal.] Beginning at the junction of the Oswego, Seneca and Oneida rivers, it shall run northward to a junction with Lake Ontario at Oswego, following the Oswego river canalized and present Oswego canal. The route of the Champlain canal as improved shall be as follows: [Champlain canal.] Beginning in the Hudson river at Waterford, thence up the Hudson river canalized to near Fort Edward; thence via the present route of the Champlain canal to Lake Champlain near Whitehall. The routes as specified herein shall be accurately laid down upon the ground by the State Engineer, who is hereby authorized and required to make such deviations therefrom as may be necessary or desirable for bettering the alignment, reducing curvatures, better placing of structures and their approaches, securing better foundations, or generally for any purpose tending to improve the canal and render its navigation safer and easier. [Prism.] The Erie, Oswego and Champlain canals shall be improved so that the canal prism shall, in regular canal sections, have a minimum bottom width of seventy-five feet and a minimum depth of twelve feet and a minimum water cross section of eleven hundred and twenty-eight square feet, except at aqueducts and through cities and villages where these dimensions as to widths may be reduced and cross section of water modified to such an extent as may be deemed necessary by the State Engineer and approved by the Canal Board. In the rivers and lakes the canal shall have a minimum bottom width of two hundred feet, minimum depth of twelve feet and minimum cross section of water of twenty-four hundred square feet. [Locks.] The locks for the passage of boats on the Erie, Oswego and Champlain canals shall be single locks, except the flight of three locks near Waterford, and of two locks at Lockport which shall be double locks. The locks shall have the following governing dimensions: Length between hollow quoins, three hundred and twenty-eight feet, clear width twenty-eight feet, minimum depth in lock chamber and on mitre sills eleven feet, and with such lifts as the State Engineer may determine. The locks shall be provided with all necessary approach walls by passes, gates and valves, with hydraulic or electrical power for the manipulation of gates and valves, for expediting the passage of boats through the locks, and for lighting the locks and approaches. All locks having over eight feet lift shall be fed through a culvert running parallel with the axis of the lock in each wall with the necessary feed and discharge pipes and controlling valves. All single locks shall be so located with reference to the axis of the canal, that a second lock can be conveniently added alongside the first should this hereafter be found necessary. [Spillways, culverts, etc.] The Erie, Oswego and Champlain canals shall be provided with all necessary spillways, culverts and arrangements for stream crossing; the bottom and sides shall be puddled wherever necessary, and the sides where necessary shall have vertical masonry walls, or slope wash walls; guard locks and stop gates shall be built where required, and in canal sections [Guard gates.] guard gates shall be built at distances apart not exceeding ten miles, all as may be determined by the State Engineer. [Bridges.] New bridges shall be built over the canals to take the place of existing bridges wherever required, or rendered necessary by the new location of the canals. All fixed bridges and lift bridges when raised shall give a clear passage way of not less that fifteen and one-half feet between the bridge and the water at its highest ordinary navigable stage. [Dams.] The dams required for the canalization of the river sections of the Erie, Oswego and Champlain canals shall be so located and shall be built of masonry or timber as the State Engineer shall determine to be best. [Buoys, etc.] Wherever, in the canalized rivers or in Oneida or Cross lakes, it may be deemed by the State Engineer necessary for the safety and convenience of navigation, spar, gas, can or lantern buoys, range lights or range targets shall be provided, placed and maintained. The eastern end of the existing Erie canal at its junction with the Hudson river shall be improved as follows: [Lock at junction of Erie canal and Hudson river.] A lock shall be built in place of existing lock number one and the weigh lock near it at Albany with the following governing dimensions: length between hollow quoins one hundred and seventy-eight feet, clear width twenty-eight feet, minimum depth on mitre sills eleven feet, and the canal prism shall be improved as far as existing lock number two by giving it depth of twelve feet and a minimum width of fifty-five feet. [Lock at Fort Bull.] And at the point of divergence from the present Erie canal near Fort Bull lock shall be constructed with the following governing dimensions: Length between hollow quoins one hundred and seventy-eight feet, clear width twenty-eight feet, minimum depth on mitre sills eleven feet, and shall be so located and constructed that boats navigating the proposed improved canal will be able to lock into the present Erie canal at this point; and that portion of the present Erie canal lying between the point above described [Orville feeder.] and the Orville or Butternut creek feeder shall be maintained as a navigable canal and feeder of its present size and depth. The outlet of Onondaga lake into the Seneca river shall be enlarged to the size prescribed for the prism of the Erie and Oswego canals, [Onondaga outlet.] and the necessary improvements shall be made in Onondaga lake to permit canal boats to reach the head of the lake, and from the head of the lake and extending southeastwardly into Syracuse where there shall be constructed a harbor or basin twelve hundred feet in length, two hundred and twenty feet in length and twelve feet in depth. [Improvement at Rochester.] From the pool in which the canal will cross the Genesee river south of Rochester, there shall be constructed generally on the side of the old feeder northwardly towards Rochester, a canal of the size prescribed for the prism of the Erie, Oswego and Champlain canals and about two and one-quarter miles long ending at the present Erie canal. The northerly end of this canal for a distance of fifteen hundred feet shall be enlarged into a basin or harbor with a width of one hundred and seventy feet and depth of twelve feet. [Water supply.] The additional water supply required for the improved Erie canal shall be provided by developing and utilizing existing sources, by constructing a storage reservoir on the Limestone creek, improving the storage of Cazenovia lake, and building storage reservoirs on the upper Mohawk near Delta and on West Canada creek near Hinckley, with all necessary feeders for connecting these and existing reservoirs with the improved canal. The supply of water for the Erie canal shall be sufficient for the uses of the canal with at least ten million tons of freight carried on it per year. (Amended by chap. 740, Laws of 1905, chap. 710, Laws of 1907, chap. 508, Laws of 1908, chap. 83, Laws of 1910 and sec. 3 of chap. 801, Laws of 1913. Improvement of canal basin at Albany, chap. 263, Laws of 1914. Retention of old canal from Waterford to Erie lock No. 2, chap. 243, Laws of 1913. Retention of old canal from Schuylerville to Northumberland, chap. 412, Laws of 1914. The terminals mentioned in the section were affected by sec. 4 of chap. 746, Laws of 1911.)

§ 4. [Appropriation of land, etc.] The State Engineer may enter upon, take possession of and use lands, structures and waters, the appropriation of which for the use of the improved canals and for the purposes of the work and improvement authorized by this act, shall in his judgment be necessary. [Appropriation surveys and maps.] An accurate survey and map of all such lands shall be made by the State Engineer who shall annex thereto his certificate that the lands therein described have been appropriated for the use of the canals of the State. Such map, survey and certificate shall be filed in the office of the State Engineer, and a duplicate copy thereof, duly certified by the State Engineer to be such duplicate copy shall also be filed in the office of the Superintendent of Public Works. [Service of notice of appropriation.] The Superintendent of Public Works shall thereupon serve upon the owner of any real property so appropriated a notice of the filing and of the date of filing of such map, survey and certificate in his office, which notice shall also specifically describe that portion of such real property belonging to such owner which has been so appropriated. If the Superintendent of Public Works shall not be able to serve said notice upon the owner personally within this state after making efforts so to do, which in his judgment are under the circumstances reasonable and proper, he may serve the same by filing it with the clerk of the county wherein the property so appropriated is situate. From the time of the service of such notice, the entry upon and the appropriation by the State of the real property therein described for the purposes of the work and improvement provided for by this act, shall be deemed complete, and such notice so served shall be conclusive evidence of such entry and appropriation and of the quantity and boundaries of the lands appropriated. The Superintendent of Public Works may cause a duplicate copy of such notice, with an affidavit of due service thereof on such owner, to be recorded in the books used for recording deeds in the office of the county clerk of any county in the state where any of the property described in such notice is situated; and the record of such notice shall be prima facie evidence of the due service thereof. [Compensation for lands, etc.] The Court of Claims shall have jurisdiction to determine the amount of compensation for lands, structures and waters so appropriated. (Amended by sec. 4 of chap 365, Laws of 1906, chap. 196, Laws of 1908, chap. 273, Laws of 1909, chap. 468, Laws of 1911, chap. 736, Laws of 1911, and sec. 4 of chap 801, Laws of 1913. Part payment for appropriated lands, chap. 708, Laws of 1913. Time for filing existing claims extended, chap. 640, Laws of 1915. Appropriation of rights and easements, chap. 420, Laws of 1916. Appraisal of lands, structures and waters provided by chap. 335, Laws of 1904. See also chap. 195, Laws of 1908, chap. 286, Laws of 1910, chap. 334, Laws of 1910, and chap. 448, Laws of 1915.

§ 4-a. (This section, inserted by chap. 63, Laws of 1910, relates to the necessary removal of cemeteries., etc.)

§ 5. [Sale of abandoned canal lands.] Whenever any lands now used for canal purposes shall be rendered no longer necessary or useful for such purposes by reason of the improvement hereby directed, the same shall be sold in the manner provided by law for the sale of abandoned canal lands and the net proceeds thereof paid into the State treasury, and so much thereof as shall be necessary shall be applied to the cost of the work hereby directed. (Amended by chap. 244, Laws of 1909 and chap. 511, Laws of 1915. The sale of abandoned canal lands is provided in chap. 50, Laws of 1909, constituting chap. 46 of the Consolidated Laws, portions of which are amended by chap. 299, Laws of 1916.)

§ 5-a. (This section, inserted by chap. 180, Laws of 1909, relates to bridges over portions of present canals to be abandoned and navigable streams.)

§ 6. [Contracts, maps, plans, etc.] All the work herein authorized shall be done by contract. Before any such contract shall be made the State Engineer shall divide the whole work into such sections or portions as may be deemed for the best interests of the State in contracting for the same, and shall make maps, plans and specifications for the work to be done and materials furnished for each of the sections into which said work is divided and shall ascertain with all practicable accuracy the quantity of embankment, excavation and masonry, the quantity and quality of all materials to be used and all other items of work to be placed under contract and shall make a detailed estimate of the cost of the same, and a statement thereof with the said maps, plans and specifications, when adopted by the Canal Board, shall be filed in his office and a copy thereof shall be filed in the office of the Superintendent of Public Works and publicly exhibited to every person proposing or desiring to make a proposal for such work. [Bids.] The quantities contained in such statements shall be used in determining the cost of the work according to the different proposals received, and when the contracts for any such work are awarded, every such statement, with the maps, plans and specifications and all other papers relating to such work advertised and which may be necessary to identify the plan and extent of the work embraced in such contracts shall be filed in the office of the State Engineer with a certificate of the Superintendent of Public Works stating the time and place of their exhibition. [Alterations.] No alteration shall be made in any such map, plan or specification, or the plan of any work under contract during its progress, except with the consent and approval of the Superintendent of Public Works and the State Engineer, nor unless a description of such alteration and such approval be in writing and signed by the parties making the same and a copy thereof filed in the office of the State Engineer. No change of plan or specification which will increase the expense of any such work or create any claim against the State for damage arising therefrom shall be made unless a written statement, setting forth the object of the change, its character, amount and the expense thereof, is submitted to the Canal Board, and their assent thereto at a meeting when the State Engineer was present is obtained. [Extra work.] No extra or unspecified work shall be certified for payment unless said work is done pursuant to the written order of the State Engineer and payment therefor shall not be made unless approved by the Canal Board. (Amended by chap. 394, Laws of 1907 and sec. 6 of chap 736, Laws of 1911. Contract obligations limited, sec. 3 of chap. 302, Laws of 1906 and sec. of chap. 66, Laws of 1910.)

§ 7. [Advertising.] All the work herein specified shall be done by contract executed in triplicate as required by law and entered into by the Superintendent of Public Works on the part of the State after having been advertised once a week for four consecutive weeks in two newspapers published in the city of New York, one of which shall be published in the interests of engineering and contracting and one each in the cities of Albany, Rochester, Buffalo and Syracuse and one in each county where the particular piece of work advertised or some portion of the same is located, and it shall be the duty of the Superintendent of Public Works to combine in one notice of advertisement as many pieces of work as practicable. The advertisements shall be limited to a brief description of the work proposed to be let with an announcement stating where the maps, plans and specifications are on exhibition and the terms and conditions under which bids will be received and the time and place where the same will be opened, and such other matters as may be necessary to carry out the provisions of this act. [Opening of bids and award of contract.] The proposals received pursuant to said advertisements shall be publicly opened and read at the time and place designated. Every proposal must be accompanied by a money deposit in the form of a draft or certified check upon some good banking institution in the city of Albany or New York, issued by a National or State bank in good credit within the state, and payable at sight to the Superintendent of Public Works for five per centum of the amount of the proposal. In case the proposer to whom such contract shall be awarded shall fail or refuse to enter into such contract within the time fixed by the Superintendent of Public Works, such deposit shall be forfeited to the State, paid to the State Treasurer and become a part of the canal fund. In case the contract be made such deposit shall be returned to the contractor. [Advertising abridged.] In cases where the estimated cost of the materials and work does not exceed ten thousand dollars, the period of advertising may be abridged and the work may be advertised by circular letters and posters when, in the judgment of the Superintendent of Public Works approved by the Canal Board, such course may be desirable or necessary. [Rejection of bids.] The Superintendent of Public Works may reject all the bids and readvertise and award the contract in the manner herein provided, whenever in his judgment the interests of the State will be enhanced thereby. [Excessive bids.] No contract which exceeds by more than ten per centum the gross cost of the work as estimated by the State Engineer or by more than twenty per centum the cost of any item therein shall be awarded unless such award shall be approved by the State Engineer and the Canal Board. [Contract made.] The contract in a form to approved by the Attorney-General shall be made with the person, firm or corporation who shall offer to do and perform the same at the lowest price and [Securities.] who shall give adequate security for the faithful and complete performance of the contract, and such security shall be approved as to sufficiency by the Superintendent of Public Works, and as to form by the Attorney-General and shall be at least twenty-five per centum of the amount of the estimated cost of the work according to the contract price. [Power to suspend, or stop the work.] If in the judgment of the State Engineer the work upon any contract is not being performed according to the contract or for the best interests of the State, he shall so certify to the Canal Board, and the Canal Board shall thereupon have power to suspend or stop the work under such contract while it is in progress and direct the Superintendent of Public Works, and it shall thereupon become his duty, to complete the same in such manner as will accord with the contract specifications and be for the best interests of the State, or the contract may be cancelled and readvertised and relet in the manner above prescribed, and any excess in the cost of completing the contract beyond the price for which the same was originally awarded shall be charged to and paid by the contractor failing to perform the work. [15% excess.] If at any time in the conduct of the work under any contract, it shall become apparent to the State Engineer that any item in the contract will exceed in quantity the engineer's estimate by more than fifteen per centum, he shall so certify to the Canal Board and the Canal Board shall thereupon determine whether the work in excess thereof shall be completed by the contractor under the terms and at the prices specified in the contract or whether it shall be done or furnished by the Superintendent of Public Works, or whether a special contract shall be made for such excess in the manner above prescribed. [Right to suspend or cancel contract and complete work.]Every contract shall reserve to the Superintendent of Public Works the right to suspend or cancel the contract as above provided and to complete the same or readvertise and relet the same as the Canal Board may determine, and also shall reserve to the Superintendent of Public Works the right to enter upon and complete any item of the contract which shall exceed in quantity the engineer's estimate by more than fifteen per centum or to make a special contract for such excess, as the Canal Board may determine. (Amended by chap. 267, Laws of 1909. Contract obligations limited, sec. 3 of chap. 302, Laws of 1906, and sec. 3 of chap. 66, Laws of 1910.)

§ 8. [Advisory Board of Consulting Engineers.] The Governor may employ at a compensation to be fixed by him, five expert civil engineers to act as an Advisory Board of Consulting Engineers, whose duty it shall be to advise the State Engineer and the Superintendent of Public Works, to follow the progress of the work and from time to time to report thereon to the Governor, the State Engineer and the Superintendent of Public Works, as they may require or the board deem proper and advisable. [Special Deputy State Engineer.] The State Engineer may appoint and at pleasure remove a special deputy, at a compensation to be fixed by him with the approval of the Canal Board, who may, under the direction of the State Engineer, perform on the work of improvement authorized by this act all the duties of the State Engineer, except as commissioner, trustee or member of any board. [Resident Engineers.] The State Engineer may also appoint and at pleasure remove such number of resident engineers in addition to those now authorized by law as he may deem necessary for the work of improvement hereby authorized and may prescribe and define their duties. (Amended by sec. 8 of chap. 736, Laws of 1911.)

§ 9. [Payment to contractors.] The Superintendent of Public Works may, from time to time, upon the certificate of the State Engineer, pay to the contractor or contractors a sum not exceeding ninety per centum of the value of the work performed, and such certificate of the State Engineer must state the amount of work performed and its total value, but in all cases not less than ten per centum of the estimate thus certified must be retained until the contract is completed and approved by the State Engineer and the Superintendent of Public Works. (Amended by chap. 416, Laws of 1914.)

§ 10. [Estimates.] All measurements, inspections and estimates shall be made by the State Engineer and the engineers and inspectors appointed by him. The Superintendent of Public Works may, in the performance of the duties devolving upon him by this act, rely upon the certificates of the State Engineer and his assistants as to the amount, character and quality of the work done and material furnished.

§ 11. [Navigation where work is in progress.] While the work contemplated in this act is in progress the canals upon which work is actually being done shall not be open for navigation earlier than May fifteenth and shall be closed on or before November fifteenth, except that portions thereof may be opened earlier and closed later when in the judgment of the Superintendent of Public Works such a course will not be detrimental to the progress of the work of improvement.

§ 12. [Canal Board duties.] All questions which under the provisions of this act are to be determined by the Canal Board, shall be decided by a majority vote of all members of such board, and a full and complete record of all proceedings of such board shall be preserved, and a certified copy of its determination or action upon any question arising under this act shall be transmitted to the State Engineer.

§ 13. [Appropriation.] The sum of ten million dollars is hereby appropriated, payable out of the moneys realized from the sale of bonds as provided by section two of this act, and from the proceeds of the sale of abandoned lands as provided in section five of this act, to be expended to carry out the purposes of this act; said sum of ten million dollars to be paid by the Treasurer upon the warrant of the Comptroller, after due audit by him, upon the presentation of the draft of the Superintendent of Public Works to the order of the contractor if for construction work, or to his own order if for the completion by him of any unfinished contract or for advertising for miscellaneous expenses connected with the said work, or upon the presentation of the drafts of the State Engineer for supervising or engineering expenses in connection with said work, or upon the presentation by the Comptroller of accounts for miscellaneous expenses, or on presentation of awards by the Court of Claims for compensation for lands appropriated as provided in section four of this act or damages caused by the work of improvement hereby authorized. (Amended by sec. 13 of chap. 365, Laws of 1906.)

§ 14. [Surplus funds.] Any surplus arising from the sale of bonds and the sale of abandoned lands over and above the cost of the entire work of the improvement of the canals as herein provided for shall be applied to the sinking fund for the payment of said bonds. (See also sec. 4 of chap. 302, Laws of 1906, and sec. 4 of chap. 66, Laws of 1910.)

§ 15. [When law shall take effect.] This law shall not take effect until it shall at a general election have been submitted to the people, and have received a majority of all the votes cast for and against it at such election; and the same shall be submitted to the people of this State at the general election to be held in November, nineteen hundred and three. The ballots to be furnished for the use of voters upon the submission of this law shall be in the form prescribed by the election law and the proposition or question to be submitted shall be printed thereon in substantially the following form, namely: "Shall chapter (here insert the number of this chapter) of the laws of nineteen hundred and three, entitled 'An act making provision for issuing bonds to the amount of not to exceed one hundred and one million dollars for the improvement of the Erie canal, the Oswego canal and the Champlain canal, and providing for a submission of the same to the people to be voted upon at the general election to be held in the year nineteen hundred and three' be approved?"

§ 16. (This section, added by chap. 494, Laws of 1907, relates to the lease and sale of water.)

§ 17. (This section relates to the sale of materials encountered in excavation and not necessary for improvement work. It was added by chap. 320, Laws of 1909, and amended by chap. 149, Laws of 1915.)

This is what is known familiarly as the Barge Canal Law. Anticipating the affirmative vote of the people, we may for a few minutes discuss this bill as the act under which the construction of the new canal was soon to begin.

Noticing only a few of its many features, we observe first in order of textual sequence that the cost was to be borne by the whole state and not by the canal-bordering counties, as recommended by the State Canal Committee in its report of January 15, 1900. The Committee's financial plan had soon run against the objection of probable unconstitutionality and had been discarded. Moreover, it had been shown that the cities along the canal, even the cities of New York and Buffalo alone, paid so large a share of all State expenditures, every public improvement as well as the proposed canal, that the small remaining portion, something less than ten per cent, was insignificant when distributed over the remainder of the state.

The route laid down in the bill deviates so widely from the course of the existing canal that it calls for comment. This divergence of routes, however, is simply the result of a difference between two types of canal-building that are even more widely separated that the locations themselves; it is the difference between the canalized river and the independent canal. Up to the commencement of the Barge canal New York had little experience in river canalization, as we understand the term today, except in the use of the Hudson river, which had never been considered as really a part of the canal system. Its nearest approach to river canalization had been the channels in the Oneida and Black rivers, which had been improved slightly for a rather limited use by steamboats, and a few stretches of the Oswego and Seneca rivers, along the banks of which towpaths had been built. Indeed river canalization is the product of comparatively recent engineering science.

The historical setting in New York state of the changes from river to canal and back again is somewhat interesting. New York is blessed by nature above all her sister states on the Atlantic seaboard in the matter of watercourses. She possesses a chain of rivers stretching more than three-quarters of the distance to the great inland seas that lie in the heart of the continent, and the mightiest of these rivers has cut a sea-level channel through the coast range of mountains, while no other river reaching the Atlantic ocean in this country is navigable to within many miles of this range. Before the advent of the white man the Indians for untold years had been using these natural avenues of travel and the first European settlers followed the same routes. But when they tried to adapt the streams to larger commercial use, they ran afoul of troubles too difficult for the skill of their day to overcome. Not only in America but in Europe as well this was the experience at that time. As Benjamin Franklin in a letter from London in 1772 quaintly puts it, "Rivers are ungovernable things, especially in hilly countries. Canals are quiet and very manageable." The first attempt to provide improved navigation in New York state was made by a private company and its field of endeavor lay in the beds of the natural streams. Before the State had begun its own first canal, however, the usual practice of the time had been adopted. In their report of 1811 the canal commissioners had said, "Experience has long since exploded in Europe the idea of using the beds of rivers for internal navigation." But now, at the beginning of the Barge canal, engineers had succeeded in making rivers sufficiently quiet and manageable to be used for navigation purposes and the State canals were to go back to the channels used for nobody knows how many centuries by the aboriginal possessors of the land.

The Barge canal law was explicit in general in its requirements as to the route, but at the same time it was not so rigid as to preclude minor deviations. In the course of construction it has happened that several changes of location have been made and in a few cases the desired change has run counter to the law and it has been necessary for the Legislature to pass an amendment before that particular new location could be occupied. It will be noticed that some cities, Syracuse and Rochester especially, are not on the direct route, but are reached through spur lines. In the case of Schenectady and Utica, also, shorter spurs have been constructed to reach their respective terminals.

For convenience it seems well to state here concisely the sizes of prism and locks and the amount of clearance at bridges, as set forth in the law. The minimum prism dimensions in land line were: Bottom width, 75 feet; depth of water, 12 feet; cross-section of water, 2,400 square feet. Governing dimensions of locks: Length between hollow quoins, 328 feet; clear width, 28 feet; minimum depth of water in lock chamber and on miter-sills, 11 feet. Clearance between water-surface and bridges, not less that 15 1/2 feet.

The law made the Canal Board the supreme governing body for constructing the new canal. This board consists of six elective State officials, the Lieutenant-Governor, the Secretary of State, the Comptroller, the Treasurer, the Attorney-General and the State Engineer and Surveyor, and one appointive official, the Superintendent of Public Works. The board was created in 1826, the next year after the completion of the original Erie canal, and has always had considerable authority over canal affairs, but the Barge canal law conferred new powers, the intent being so to place the responsibility for the proper conduct of the work upon this body of men, high in the government of the State and directly answerable to the people for their actions, that there could be no possibility of a repetition of former alleged abuses.

The Canal Board, although it originated many years ago, is in exact accord with present-day business methods. Great modern corporations find it advisable to have their affairs governed by a small body of men who are chosen because of their peculiar qualities of keen business acumen and sound judgment and their irreproachable characters and who are in a position to have a broad grasp of the whole business without being worried with administrative cares. In the construction and maintenance of its canals the State is engaged in a mighty business enterprise. The people of the state may be called the shareholders in this business and not only is the money they have invested at stake but the success of the enterprise means added prosperity to them as individual citizens as well as to the State as a whole. In this great State corporation the Canal Board occupies the position of Board of Directors, and the stockholders, namely, the people of the state, directly elect six members, while the seventh is the representative of the other chief elective State official, the Governor, who is not himself a member. The wisdom of providing such sagacious and faithful oversight as this Board has given to the undertaking is seen throughout the whole course of Barge canal construction.

Upon the Governor also the Barge canal law placed more responsibility than he had formerly had in canal matters. Through a newly-created board, which was ordered to report to him, he was supposed to keep in close touch with the new canal at all times. The law laid on him the appointment of this body and it was to consist of five expert civil engineers, who were to act as an Advisory Board of Consulting Engineers and whose duty it should be to advise the State Engineer and the Superintendent of Public Works and to keep a watchful oversight on the work as it progressed.

Direct responsibility for planning and construction devolved upon the State Engineer and in order that he might have proper assistance the law gave him power to appoint a Special Deputy State Engineer and also such number of Resident Engineers as he deemed necessary, the Special Deputy to have immediate charge of the entire new work and the Resident Engineers to have charge of the several departments and sections.

The influence of some of the unfortunate circumstances attending the nine-million improvement is plainly discernible in this law. To this earlier experience may be ascribed the fuller powers of the Canal Board and the State Engineer. The new board of Consulting Engineers and through them the increased care on the part of the Governor were precautionary measures dictated by this same experience. Especially in the matter of awarding contracts and prosecuting contract work was the influence of the former project seen. New restrictions were added. The usual measures to safeguard the State were all there but their provisions had been so tightened as to make them operate with more stringent force. The thing which the law aimed chiefly to prevent was the unbalanced bid, that bête noire of the engineer, from which by various devices he has ever attempted to escape while yet he should retain a force of proposal and contract flexible enough to provide for emergencies. To accomplish this result the law directed that the State Engineer should make public not only the estimated quantities of each item of material or labor for any piece of work it proposed to put under contract, but also his estimate of cost for each of these items. Then it forbade the awarding of a contract on any bid the total of which exceeded the engineer's total by more than 10 per cent or any item of which exceeded the engineer's estimated cost of that item by more than 20 per cent, unless the State Engineer and the Canal Board should formally approve such contract. As a further precaution against an unbalanced bid a contractor in performing his work was not allowed to exceed in quantity any item of work more than 15 per cent without authority from the Canal Board, and this Board, if it saw fit, instead of letting the original contractor perform this work in excess of the 15 per cent might order the Superintendent of Public Works to do it or might decide to have it done by awarding a new contract.

The law ordered that all plans and specifications should be prepared by the State Engineer and approved by the Canal Board before the letting of contracts and that after the contracts were awarded these plans and specifications should be carried out without alteration except as the State Engineer and the Superintendent of Public Works should consent to and approve some alteration and a description of such alteration and such approval should be put in writing and signed by these officials and a copy filed in the office of the State Engineer. No extra or unspecified work was to be certified for payment unless such work was done pursuant to the written order of the State Engineer and no payment for this work could be made until it had been approved by the Canal Board. The form of contract to be entered into with the contractor was to have the approval of the Attorney-General. Since the records of canal transactions were open to the public the people might at all times know exactly what was being done in prosecuting the great undertaking they were being asked to approve.

There have been times during the years of construction when some of the provisions of this law have seemed to involve a useless amount of red tape, and doubtless these restrictions have been the cause of various delays, but the chief thing aimed at has been accomplished -- the canal has been built and there has been no suspicion that anything connected with its construction has been other than what it should be. This condition of course is due in large part to the high character of the men charged with the duty of administering canal affairs, but in general the same may be said of some of those who had authority over the nine-million improvement but who by implication suffered unjust blame, largely because they were working with a law that contained loopholes through which the unscrupulous might escape.

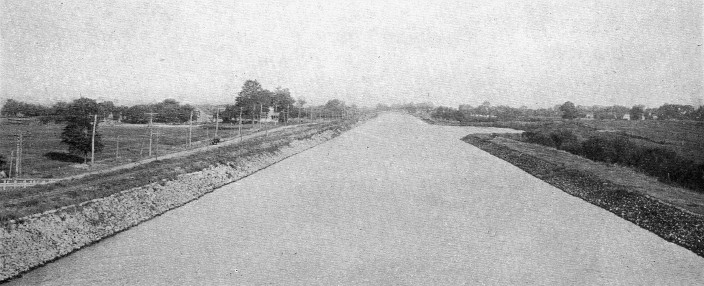

Dam at Delta reservoir, impounding the waters of the upper Mohawk river and the diverted Black river supply, for delivery to the Rome summit level of the canal. A portion of the Black River canal, submerged by the reservoir, was relocated, being carried across the river on an aqueduct, up the steep acclivity by a flight of locks and along the reservoir edge on high ground.

Now we come to the real battle between the canal and the anti-canal forces. The preceding skirmishes had been important and were bitterly fought, but in a sense they had been only preliminary and the victories already won might still be turned to defeat, since the question was being submitted for final decision to the electorate of the whole state. Now the decisive conflict was on. Now the case was being tried before the court of last resort -- the people -- and from the plebiscite about to be given there was no appeal. It is not to be wondered at then that both sides were alive to every opportunity and that neither spared any pains to achieve its ends.

The campaign which was waged was distinctively a campaign of education. Probably no other question of economic import has ever been so carefully set before the people of the state. And yet on the day when the decision was to be made one-eighth of all the voters who went to the polls, a sixth of a million persons, failed to vote either for or against the canal proposition. But even so the proportion of those who took interest enough to cast a vote was much larger than is the case with most public questions submitted to popular referendum. Why the largest single project ever undertaken by a state should have been a matter of indifference to so many of its citizens seems strange on first thought. The reason is to be found in the popular conception of the importance of political campaigns. The majority of people have come to look upon these as momentous events in our political history and this view dwarfs any economic question brought to vote, even though it be of the gravest consequence.

Why this should have been a campaign of education is readily discernible. The defeat of the amendments proposed by the Constitutional Convention of 1867 was still remembered, and these had failed of approval largely because the people did not understand their provisions. The canal bill dealt with intricate and technical subjects -- finance, engineering, a route largely divergent from the existing canal, adequate water-supply, a plan with novel features for letting contracts -- and moreover the expenditure involved was enormous. If for no other reason the project might easily fail from lack of understanding, and canal advocates were well aware of this danger. With a powerful army of active hostility to be met and overcome, with the vast throng of the interested but uninformed to be instructed, with those in the wide, outlying regions to be convinced that the canal would benefit all, and, worst of all, with the mighty concourse of the apathetic to be quickened into life, canal men saw that their only chance for success lay in conducting a vigorous and convincing campaign of education. Naturally the opposition adopted the same tactics.

The first event we shall record in the canal campaign scarcely belongs in that category; it partakes rather of the nature of a jubilee, but there were certain results coming from this occasion which made it worthy of notice. On May 9, 1903, the Merchants' Exchange of Buffalo gave a dinner to General Francis V. Greene, Major Thomas W. Symons, John N. Scatcherd and Edward A. Bond, members of the State Committee on Canals, and to the legislators of Erie county, who had been at the forefront of the legislative contest. The dinner was attended by a large number of prominent men, chiefly from Buffalo, and speeches on the canal question were made. Its significance lies in the example set for commercial bodies in other cities throughout the state to hold similar public meetings for the discussion of canal matters; also in the trend given to arguments to be used later in gaining votes for the cause.

Canal men realized of course that they had a hard fight on their hands and they organized their forces to meet the occasion. Early in May a Canal Improvement State Committee was formed to direct the whole campaign, with headquarters in New York city. This committee was composed of Gustav H. Schwab, Henry B. Hebert and Frank Brainard of New York, John W. Fisher and Robert R. Hefford of Buffalo, Frederick O. Clarke of Oswego and Frank S. Witherbee of Port Henry. Closely associated with them and coöperating in some of the work were George Clinton, chairman of the Canal Enlargement Committee of Buffalo, and E.L. Boas, treasurer of the Canal Association of Greater New York. John A. Stewart of New York and George H. Raymond of Buffalo were appointed secretaries, Mr. Raymond taking charge of the literary bureau, to prepare and disseminate canal literature. Mr. Schwab was chosen chairman of this State Committee and he labored zealously for five months or more, so zealously indeed that toward the end of October his physician advised him to go away for a needed rest. Charles A. Schieren, ex-Mayor of Brooklyn, succeeded to the chairmanship for the remaining two weeks of the campaign and his activity put new life into the cause at a time when it was much needed.

To reach the voters this committee worked through four main channels -- newspapers, printed literature, such as pamphlets and the like, speakers at public meetings, and labor unions or other organizations. The opposition carried on a campaign in much the same way.

The pro-canal endeavors were concentrated along the line of the canal and especially at its termini. The outlying territory was conceded to the opposition, but, as will appear later, before the campaign ended the war was carried also into the enemies' country.

Under the State Committee Howard J. Smith of Buffalo was appointed to take charge of the newspaper work. Mr. Smith had been doing this kind of work for several years, especially during the publicity campaign of 1900-1901. He organized the new work as before and was soon supplying country weeklies with "plate" and the city papers with special articles and interviews. It is said that during the final months of the campaign plate matter was being furnished to 750 papers. To Mr. Smith personally was assigned much of the work of devising arguments for canal improvement, preparing articles, and writing and revising speeches and addresses.

The New York city press was in favor of the canal project with only two important exceptions -- the Sun and the Herald. The Sun was unalterably opposed, keeping up a daily attack and pouring out invective, ridicule and argument in nearly every edition. Mr. Schwab tried to change the attitude of the Herald by cabling James Gordon Bennett in Europe and urging him to instruct his editors to support the movement, but no reply was received. The Buffalo papers were solidly with the canal men and the rest of the state was lined up just about as it had been through all the years of this agitation.

In the way of canal literature a vast amount of letters, pamphlets, leaflets and posters was distributed. The Canal Improvement Text Book, a pamphlet of 168 pages, was the most important in this class. It was prepared in large measure for the use of speakers and editors, but the edition was ample and it found its way to the public generally. It was a veritable storehouse of information in compact form. It contained the substance of the canal bill, considerable portions of both the State Engineer's report of the preliminary survey and the report of the State Committee on Canal's testimony of experts on the reliability of the surveys and estimates, opinions of prominent men and representative commercial organizations regarding the necessity of the canal, speeches delivered at legislative hearings, reports on the canals of certain foreign countries and numerous other bits of pertinent canal data. In addition to the Text Book a large edition of the Canal Primer was printed and distributed. This is the pamphlet which has already been mentioned as having been put out in the form of questions and answers.

A systematic effort was made to secure endorsement of the canal question by labor unions throughout the whole state. This subject came up early in the spring, even before the bill passed the Legislature, and Warren C. Browne, then of Buffalo, was given charge of this phase of the campaign. The project was presented to nearly every labor organization in the state and was generally approved. It was a matter naturally calculated to appeal to labor unions. Even the building of the canal would give employment to many thousands through a decade or more and if expectations were realized the canal would usher in a period of industrial development in which labor unions might share bountifully. This work among the unions proved worth while. Their vote did much to offset adverse sentiment in the interior counties. An analysis of the vote shows that in the strongest anti-canal sections a good sized minority vote was polled wherever there were labor organizations.

Of a somewhat similar character was the attempt made to get support through the political parties. Committees conferred with the speakers bureaus of the Democratic , Republican, Citizens' Union, Socialist Labor, and Prohibition parties. The Citizens' Union agreed to have its campaign speakers advocate the canal. Another type of mass activity was the systematic work undertaken among the Italians throughout the state. This was in the efficient hands of John J.D. Trenor, member of the New York Produce Exchange, who by reason of a long residence in Italy and a mastery of the Italian tongue was eminently fitted for the task.

Before we proceed with the remaining activities of the canal forces, which we desire to follow in a somewhat orderly chronological fashion down to the eve of the election, we shall see what the opposition was doing.

In respect to funds the opponents had a definite advantage over the canal men. They seemed never to lack money. It was charged that the railroads were back of most of the anti-canal activity and were paying the greater part if not all of the expenses.

The opposition of the large cities along the line of the canal is hard to explain. One would naturally expect them to favor the project. It is not fair to say that railroad influence and personal interests were responsible for all of this attitude. There were, doubtless, multitudes of men with no individual interests at stake who steadfastly believed that the proposed canal was not for the highest good of the State. But at the risk of being thought prejudiced we dare to assert that at bottom most of the opposition was due to some interest of a personal nature, the railroad influence predominating. And this personal interest, working through the press, molded public sentiment in various areas of the state and thus gave to the man with no personal interest an opinion which he accepted as his own. This is not saying, however, that individual interests did not hold sway to a considerable extent also in the canal camp. But speaking by and large the canal advocates were more often actuated by altruistic motives, while the opponents were generally influenced by consideration of personal gain.

The opposition of the rural sections might naturally be expected; the same attitude had existed for years. The reasons for it, however, need not concern us now; it is sufficient to say that the organized opposition played upon this sentiment, while those of the other side did what they could to change it.

An anti-canal bureau was organized in Brooklyn, for which literature was distributed. But the center of activity was in Rochester and strangely the Chamber of Commerce of that city was at the forefront of this activity, its secretary, John M. Ives, being the director of the anti-canal forces of the state.

As a sample of the literature distributed by the opposition we may cite a pamphlet entitled, "Twenty good reasons why you should vote No," compiled under the auspices of the Rochester Chamber of Commerce. It embodied editorials from the Engineering News, the New York Sun, the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, Union and Advertiser, Herald and Post-Express, the Utica Press, the Albany Argus, the Syracuse Post-Standard, the Binghamton Leader, the Ithaca Journal and several other papers, also speeches made by Senator Merton E. Lewis and ex-Assemblyman Brownell of Broome county, and articles written by John A.C. Wright, E.B. Norris, master of the State Grange, George Bullard, John M. Ives, secretary of the Rochester Chamber of Commerce, George W. Rafter, D.H. Burrell of Little Falls, and others.

An anti-canal State convention was held at Rochester and one of its chief figures was John I. Platt of Poughkeepsie. Through Mr. Platt's activities the railroad influence was plainly seen at this convention and he frankly admitted that the New York Central Railroad was paying his expenses.

On May 25 there was issued a long circular signed by sixteen State senators, who came from the farming districts of the state. In effect this was a solemn manifesto warning the people against the efforts of New York and Buffalo to carry the canal bill. That these cities were to pay for most of this improvement and were yearly paying many millions in taxes to the direct benefit of the rural communities was entirely ignored. A formal reply to this circular was put out by the Canal Improvement State Committee on June 10.

The opposition was surely aggressive. That it was also unscrupulous in statement, both in the public press and in other literature, is charged by the advocates. If the specimen given below is a fair sample, the charge seems to be sustained. It is a handbill which was distributed at elevated railroad stations and at other places in New York city where people congregated in masses. We do not attempt to copy more than the words; the type and arrangement were such as to attract attention. It reads as follows:

"Vote, but vote No on the Barge canal scheme. Beneficiaries: Grain speculators, the contractors, the padrones. Who pays for it? You.

"This means higher taxes, direct and indirect. The latter touch everybody. Higher rents, higher licenses, heavier expenses, with no return. Vote No.

"If there is any intelligent man who thinks it will benefit the State or any section therein or any citizen thereof, save only the beneficiaries of the most stupendous graft ever suggested, let him vote for the Barge canal. If he is not a grafter and if he has any regard for his own interest let him vote No."

Comment is hardly necessary. In the case of the thinking man such literature must often have proved a boomerang. But it was not meant for him; it appealed rather to the discontented, those who were ready to see only guile and evil in others. Moreover it was a treacherous attack on the Government, and insidious implication that the State was willing to countenance "the most stupendous graft ever suggested." When we consider the motive underlying this attack and we know that it was merely a cloak to cover selfish and unworthy ends, we appreciate its base character. Of such stuff are the acts which constitute the gravest menace to our American ideals. If anything like this handbill was issued by canal men, we have failed to see it. Their literature was not so sensational; a becoming dignity marked its language and its appeal was to the reason. In the end these were the tactics which won.

In the campaign program of the canal advocates the public meetings and the speakers bureau held important places. The meetings were held all through the summer and fall, increasing in number and frequency as election approached, particularly in New York city. We cannot enumerate the whole list but shall mention some of the most prominent.

On July 28 a dinner was given in Utica under the auspices of the Canal Improvement State Committee. Some three hundred were present, business men, editors of local papers and representatives from neighboring cities and towns. Horatio Seymour, Jr., ex-State Engineer, presided, and one of the speakers was Philip W. Casler, ex-president of the State Grange. Aside from the jubilee banquet at Buffalo this was the beginning of the State-wide contest. One of the speakers called attention to the fact that it was eminently fitting that the first gun of the campaign for canal enlargement should be fired at Utica, for it was near-by, in Rome, within the same county, that the first sod was turned eighty-six years before in the construction of the original Erie canal. The influence of this dinner was felt throughout the whole immediate vicinity.

A somewhat similar conference and dinner was arranged at Syracuse for the editors of Central New York.

On August 1 a large meeting was held at Three River Point, a summer resort lying at the confluence of Oneida and Seneca rivers, which unite to form Oswego river. For years the people of the vicinity had been accustomed to hold an immense Farmers' Picnic at this place and the location was well calculated to draw a large crowd. A like meeting was held at Sylvan Beach, a summer resort at the eastern end of Oneida Lake. These two places are will known names geographically in Barge canal history, since they stand at strategic points in the line of the new canal. Incidentally it may be said that new canal construction at Three River Point has wiped out the old picnic grounds.

The various county fairs were convenient occasions for disseminating canal ideas, through both literature and public speaking. At some of these fairs Governor Odell spoke very cogently for the canal project, appealing particularly to the farmers, and as these speeches were given wide publicity they must have gained many votes.

Another form of campaigning was one that was engaged in jointly by the opposing sides -- debates at public meetings. John I. Platt was the anti-canal exponent and Senator Henry W. Hill and Willis H. Tennant of Mayville were severally his opponents. Senator Hill and Mr. Platt met in debate at Troy on October 5 and both were scheduled to speak at the same meeting on one other occasion, the Wayne county fair, on October 24, but Mr. Platt and other anti-canal speakers did not keep this latter engagement. But most of the debates were between Mr. Tennant and Mr. Platt. They met at Plattsburg, Three River Point, Elmira, Utica, Cassadaga, Brocton, Binghamton, Dunkirk, Syracuse and the Chemung county fair. This series of debates evoked considerable interest, especially in the rural districts, where little concern had been manifested before. The speeches were interspersed with anecdote and repartee, much to the amusement of the audiences. Mr. Platt was resourceful in argument, a careful student of transportation questions and a skilled debater, but Mr. Tennant was no less resourceful and well informed and in addition he had the advantage of being in closer touch with the temper and conditions of rural communities, understanding their prejudices and also what lay back of these prejudices. It is probable that on the whole these debates gained votes for the canal. It is said, for example, that there was not a single person favorable to the canal in Plattsburg before the debate, but at the election seventy votes were cast for it; also that somewhat similar results were shown in other towns.

We have had occasion to mention Mr. Platt several times. He was the most aggressive and persistent opponent of the Barge canal project during the whole course of its agitation and probably he was the most able opponent as well. Most of the adversaries were content to lay down their arms when the canal forces won at the polls, but not so Mr. Platt. He was not yet beaten. He appealed to the courts in an attempt to prove the Barge canal law unconstitutional. What was said of him during his campaign is pertinent here. "He is the avowed foe," said the New York Times, "not merely of canal improvement, but of canals. If he could have his way the canals would be abandoned and the railroads would get a monopoly of the transportation business. He is not a critic of the plans, nor an advocate of any particular kind of canal. All canals are equally odious to him. Nor is it the frightful sum of one hundred and one millions that scares him. If a canal 43 feet deep and 205 feet wide could be dug straight across the State from the Hudson to the Lake for a dollar and a quarter, he would sturdily oppose the project."

There was another type of debate which, perhaps, did not influence the vote of 1903 but which should be mentioned because of the impressions probably left on the minds of the youthful debaters. The canal question was well suited to academic discussion and students in many educational institutions were eager to get literature and engage in debates. And these debates carried the campaign into the territory where anti-canal feeling was most intense and where a professed advocate might not have been given a courteous hearing. The students naturally were open-minded and had not the bias of their elders and the debates must have left some impress. Of course the influence from this source could have been only a drop in the bucket, but it is a fact that the three canal referenda submitted to the people since 1903 have been carried with but little effort on the part of canal advocates. Except for the thorough educational campaign of 1903, this could hardly have happened.

Of the remaining work throughout the state, except in New York city, little more need be given here that an enumeration of the more important meetings. The first gathering of size in the southwestern part of the state was at Lilly Dale, Chautauqua county, on August 22. In Jefferson county the campaign was opened at the Republican convention. A meeting was held in Troy in August. On September 16 a large company gathered at the Utica Chamber of Commerce and listened to speakers from both camps. At Jamestown on September 19 a meeting was addressed by a prominent leader in the State Grange, who advocated the canal side. The Tonawanda Board of Trade held a banquet for its business men, who gave attention to a speech favoring the canal scheme. On October 15 a canal meeting was held in Dunkirk. The next night a meeting under the auspices of the Cohoes Business Men's Association the effect the proposed canal would have on water privileges at Cohoes was discussed before in interested audience. Another large meeting was held under the auspices of the Troy Chamber of Commerce on October 27. Two days later a mass meeting was attended by nearly all the prominent business men of Lockport. Of course there were many other meetings, but this list will suffice. One canal enthusiast traveled through the state delivering illustrated lectures on the benefits of water transportation and showing the need of improved channels and adequate terminals if the commerce of the state were to be retained.

But the chief battle ground in this whole campaign was New York city and in the end it was New York city that carried the day. The canal men from this city had been the first, more than two years earlier, to take a firm stand for the 1,000-ton improvement and now, when the time came for consummating their work, they all joined loyally in the stupendous task and came up to the Bronx on election night with nearly three hundred thousand votes to spare, enough, after offsetting the adverse vote of a little less that fifty thousand in the up-state section, to carry the proposition by close to a quarter of a million majority. Lesser New York city, the old city, did even better proportionately. The vote in New York county, practically the old city, was 252,608 for and 28,979 against, or only about one opposed to the project in every ten voters.

When we recall the events of nearly a century earlier, what a commentary is this vote upon New York city's appreciation of her canal! In the light of subsequent history we cannot understand the early attitude, but when the bill to authorize the original canal was before the Legislature in 1817, every member from New York city was opposed. In the debate just preceding the vote the most masterly speaker had appealed to the members from New York, but to no avail. "If the channel is to be a shower of gold," he had said, turning to a leading member of the New York delegation, "it will fall upon New York; if a river of gold, it will flow into her lap." This became a true picture and in 1903 New York made reparation. Whatever may be one's opinion of the value of canals at the present time, he must admit that the original Erie canal was the chief factor in retaining for New York the proud title of Empire State and in making New York city the commercial metropolis of the continent. He cannot dispute this statement. The fact is too well attested; it can be demonstrated with almost mathematical precision.

New York city was well organized for the contest. The Canal Improvement State Committee, the body organized to direct this campaign of 1903 throughout the whole state, had its headquarters in New York. Here also was the Canal Association of Greater New York, which was formed early in 1900, at the beginning of agitation for a barge canal, and which had been doing yoeman's service ever since. In addition, on September 14, 1903, the canal committee of the Produce Exchange organized a Canal Improvement League, composed of fifty members of the Exchange, under the leadership of Albert Kinkle. It was through these organizations that the various interested commercial bodies and the many enthusiastic individuals in New York city labored. All through the campaign they worked, and ardently at that, but as the time of final decision drew near their efforts were multiplied many fold and the contest was closed in a whirlwind of fervor, both sides, indeed, being active to the last day.

We shall mention only the meetings of the last month of the campaign in New York city. In spite of all that had been done throughout the state, canal men were exceedingly apprehensive of the issue and an appeal was made to the New York city commercial bodies. On October 6 a dinner was given at Delmonico's by the Canal Association of Greater New York to the editors of the metropolitan press, forty representatives being present, as well as canal advocates from various parts of the state. The long articles in the papers as a result of this dinner and the subsequent leading editorials that appeared almost daily awakened New York city to the importance of the measure about to be voted upon.

To focus the city's aroused attention on the subject at hand these activities were followed by a very generous distribution of canal literature and a most intensive campaign of cart-tail meetings, the latter being under the management of William F. McConnell, of the Board of Trade and Transportation. Sixty speakers were engaged in this cart-tail campaign and literature was distributed at more than 1,000 mass meetings and also at all ferries and many factories.

On the same day as the press dinner, October 6, the Board of Aldermen of the city, at the solicitation of the Canal Association of Greater New York, adopted resolutions in favor of the canal project.

On October 20, under the auspices of the Canal Improvement League, there was held a mass meeting on the floor of the Produce Exchange. Among the speakers were Mayor Seth Low, two ex-Mayors of Brooklyn, Charles A. Schieren and David A. Boody, and other men prominent in business, civic and educational affairs. George B. McClellan, who became Mayor the next year and who had been invited to address the meeting but was prevented from attending by a previous engagement, sent a letter expressing his sympathy for the canal cause. The League also distributed a great number of campaign buttons and badges.

Almost on the eve of the election, on October 26, the United States Supreme Court rendered its decision in the case of Perry vs. Haines, which held that the Erie canal, though lying wholly within New York state, by reason of connecting Lake Erie with the Hudson river forms a part of a continuous highway for interstate and foreign commerce, also that it is a navigable water of the United States as distinguished from a navigable water of the State, and that boats navigating this canal are within the contemplation of the maritime law, over which the Federal courts exercise admiralty jurisdiction.

Subsequent experience has shown that this decision has had little effect on either the practical operation of the canal or the navigation upon its waters, but coming as it did, only a week before election, the anti-canal press of the state was quick to seize upon it as a decision favoring their side, declaring that it dealt a hard blow to the State canal. In the few days thereafter there was no adequate opportunity for canal advocates to acquaint the voters with what they considered was the true import of the decision. The anti-canal use of this decision seems to have been merely by implication rather than by definite statement of what its actual effect on the canal would be. As a specimen of this type of argument we may quote from a letter addressed to the electorate of New York city on October 29 by Andrew H. Green, advising a negative vote on the canal referendum. Without further explanation Mr. Green simply said, "The remarkable decision of the United States Supreme Court given out yesterday, establishing admiralty jurisdiction over the Erie canal, is another formidable reason against the construction of this barge canal, the full effect of which is not yet fully realized."

The last meetings of the campaign were mass meetings held in Cooper Union on October 30 and some other mass meetings held in Brooklyn and Staten Island.

On Monday, November 2, the day before election, all of the metropolitan papers except the Sun, the Herald and the Telegram published a letter signed by prominent men in favor of the canal project. The men signing this letter were Seth Low, R. Fulton Cutting, Chas. A. Schieren, Gustav H. Schwab, William F. King, Robert Campbell, Thos. J. McGuire, Frank S. Witherbee, Lewis Nixon, George B. McClellan, Bird S. Coler, Oscar S. Straus, David A. Boody, Fred W. Wurster, Henry Hentz, Herman Robinson, William McCarroll and Henry B. Hebert.

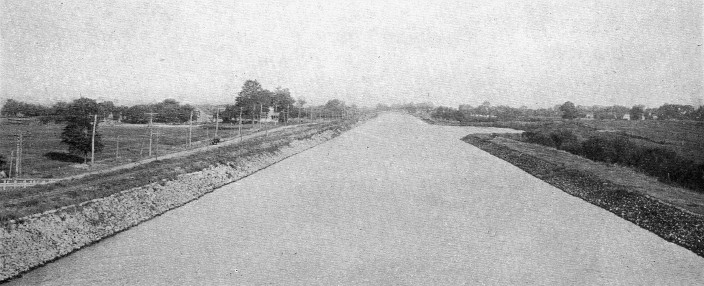

Channel in a land-line. There are land-line sections at many localities, but the view is especially typical of much of the canal in the western part of the state, where in general the old canal was deepened and widened. A turning basin is seen in the middle distance.