HISTORY OF THE BARGE CANAL

OF NEW YORK STATE

BY NOBLE E. WHITFORD

CHAPTER V

LEGISLATIVE CONTEST OF 1903

Importance of Year 1903 in Canal History -- Governor's Message Arouses to Action -- Reimposition of Tolls Suggestion -- Combatted by Canal Men -- Governor Recommends Thousand-Ton Canal -- Suggests Electric Towage May Obviate Its Necessity -- Thousand-Ton Canal Bill Introduced -- Hearings on Bill -- Accuracy of Estimates Upheld -- Revised Estimate Ordered -- New Estimate Shows Large Increase in Cost -- Bill Amended -- Counter Bills: Railroad Schemes: Proposal to Permit Sale of Canals: Electric Towage Proposal: Bill to Reimpose Tolls: Federal Waterway Plan -- Gigantic International Canal and Water-Power Project Launched -- Attitude of State Press -- Other Opposition -- Canal Organizations Active -- Canal Bill Progressed -- Senate Contest -- Effect of Tammany Support -- Measure Passed by Senate -- Assembly Approves After Strenuous Fight -- Signed by Governor.

With but one possible exception the year 1903 is the most momentous year in New York State canal history. The only other which rivals it is 1817, the year when the State decided to build the original Erie and Champlain canals. Compared with the waterways which the people determined in 1903 to build, the canals undertaken in 1817 seem pitifully small, but considering the differences of times and conditions the State embarked on the larger enterprise in 1817 and one fraught with vastly greater difficulties and hazards. In that day the nation was young and its financial resources small. The whole state had only one-fifth the population of New York city today. Engineering was an unknown profession in America. The track of the canal was an unbroken forest or a miasmal marsh. People denounced the scheme as visionary. President Jefferson declared it a century ahead of its time. President Madison thought its cost would exceed the resources of the whole country and refused aid. The National government would not help even by granting its unsalable western lands, which the canal eventually transformed in flourishing States. For New York alone and unaided to undertake the work was considered by many as equivalent to dooming the State to bankruptcy. In derision it was said that in Clinton's "big ditch would be buried the treasure of the State, to be watered by the tears of posterity."

Strong and determined men were needed to guide the canal project in those early days and we have come to look upon them as the leaders of their time, gifted with the most far-seeing vision, imbued with the most perfect patriotism. So, too, the men who guided the canal project of 1903 through the vicissitudes of that year and the difficulties of later years were strong and determined and history has accorded them a high place among the men of their day, and doubtless future generations, far enough removed to get the true perspective, will bestow a still higher award.

We shall have to review the events of 1903 at considerable length, so many and varied were the activities, so important and wide-reaching was the decision then made, so immense was the enterprise begun.

The Governor's annual message to the Legislature of 1903 sounded the note which aroused to action both the friends and the adversaries of the canals. These was one feature of this message which had been anticipated by some of the friends and concerning which we desire to speak now, so that later the continuity of events may not be interrupted.

The Governor said that in case the large canal scheme should receive legislative approval he would "recommend the adoption of a concurrent resolution providing for the reimposition of limited tolls, which would perhaps produce revenue enough to provide for the maintenance of the canal, believing that the lowering of the freight rates would be so great that a tollage could be easily met without interfering with the results which it hoped to accomplish under this plan."

On the 18th of December preceding, the committee on canals of the New York Produce Exchange and the sub-executive committee of the Canal Association of Greater New York had adopted a report and a resolution of committee on tolls and had sent a copy of these to the Governor. A few of the statements contained in this report are worth quoting. Among them is a letter written by ex-Governor Horatio Seymour in 1882, when the proposition to abolish canal tolls was pending in the Legislature.

"Many seem to think," said Mr. Seymour, "that the question involved in the pending amendment is only to determine if the canals should be supported by those who use them, or by taxation upon all parts of the State. This is very far from being a true view. Tolls are taxes of the most hurtful kind to the whole community. ... The object of the amendment is not only to relieve our boatmen and to save our canals, but to lighten taxation in every part of the state. That it will do this can be shown not only by reason, but more clearly by experience. When our canals were first projected, they were opposed because it was feared that, while they might benefit some sections, they would injure others away from their lines. This proved to be the reverse of the truth. The wise way to lighten taxation is to add to the wealth and prosperity of the community. Since the completion of the canals the ration of taxation upon the extreme northern and southern sections of New York has been reduced, while the markets for their products have been improved and enlarged.

For years New York had been made to suffer under railroad discriminations and how this condition affected the question of tolls the report went on to explain. It said, "Your committee are well aware of the fact that, as far as they are informed, all foreign canals are operated under the toll system and that, therefore, is no reason why the proposed improved waterway, ranking second only to the proposed Panama canal, should form an exception to the rule. But your committee venture to urge that the Erie canal plainly occupies a position radically different from that of any other canal in that it forms the sole possible competitor of the numerous and powerful and allied railroad lines leagued together for the purpose of so directing traffic so as to deprive the State and City of New York of that share of commerce to which they are entitled. ... Your committee believe that the rules applicable to other canals cannot obtain here."

The committee had made careful inquiry and had learned that the general feeling in New York city business circles was that the reimposition of canal tolls would be a step backward and a grievous blunder.

Recurring now to the Governor's message, we find him reaffirming his belief in the thousand-ton barge plan and urging most strongly upon the Legislature the necessity for immediate action, and saying, "We should recollect that above every other claim the prosperity and upbuilding of our State are foremost. While giving all weight to the expense involved, we should not be deterred from any expenditure that will hold the supremacy of which we are all justly proud."

"In my last message," he said further, "I advocated the deepening of the canals to a nine-foot level with locks capable and large enough to provide for one thousand-ton barge tonnage. To this subsequently suggestions were added that both the Oswego and the Champlain canals should be equally enlarged. This proposed measure failed of passage, I am convinced, because of an honest belief upon the part of many members of the Legislature that the plan proposed was inadequate to meet the requirements of commerce."

Besides the proposal to reimpose tolls, of which we have already spoken, there were two other features of this message that gave encouragement to canal opponents. One was the immensity of the cost as it was made to appear if interest were included, and it was in this form that the Governor presented the project. Taking the estimate of the 1900 survey and adding interest at three per cent for fifty years the total cost, the Governor said, would be $193,980,967.50, and if the Champlain canal should be deepened to 12 feet, as was then desired by canal advocates, rather than to 7 feet, the whole cost, principal and interest included, would be $215,000,000. The other feature was a suggestion that electrical equipment for rapid haulage over the existing canal might obviate the necessity of constructing a 1,000-ton canal.

On January 13, 1903, the executive committee of the Canal Association of Greater New York formally adopted the canal bill is it had been prepared by Messrs. Blackmar, Symons, Clinton and Hill and two days later it was introduced in the Assembly by Charles F. Bostwick of New York. It carried an appropriation of $81,000,000 and provided for deepening the Erie and Oswego canals to 12 feet and the Champlain to 7 feet.

A conference of canal men from various parts of the state was held in Albany on January 26 and as a result the bill was modified in some respects and the bond issue was raised to $82,000,000. In this form it was introduced in the Senate by George A. Davis, Chairman of the Senate canal committee, on January 28. One of the modifications increased the Champlain locks in the Hudson river section to the same size as those proposed for the Erie and Oswego canals.

All through the legislative contest of 1903 the adversaries of the canal were alert and persistently active. Immediately upon the introduction of the canal bill they demanded $50,000,000 for good roads. The friends were no less vigilant and busy. They appeared in numbers at the several hearings; through their organizations they were constantly in touch with the legislative situation and were ready for all emergencies.

Three joint hearings were held on the canal bill and among the men to appear in favor of the measure were several of those who had stood by the cause for years, such men as Henry B. Hebert, Gustav H. Schwab, William F. McConnell, Captain William E. Cleary and William F. King of New York and George Clinton, Henry W. Hill, John Laughlin and George H. Raymond of Buffalo; also prominent engineers who had been connected in an advisory capacity with various parts of the canal investigations, Major Thomas W. Symons, David J. Howell, George S. Morrison and William H. Burr, while Alfred Noble, then President of the American Society of Civil Engineers and in charge of the Pennsylvania railroad tunnel sent his opinion by letter. The framer of the canal bill, Abel E. Blackmar, also appeared. In opposition there were present representatives of the State grange, those who favored a Federal ship canal or some other scheme, those who objected because of opposition to canals in general or on account of certain features of this particular canal, and also John I. Platt, who represented the railroad interests and was the most persistent and ubiquitous opponent of all.

At these hearings the trustworthiness of the State Engineer's estimates was attacked. To combat this attempt of the adversaries to discredit the figures several eminent engineers were called upon to give their opinions. What two of them said is worth noticing, even to their exact words.

In a letter to Mr. Davis, chairman of the Senate canal committee, Alfred Noble said:

"At a meeting held on February 5, 1901, the Board of Advisory Engineers, of which I was a member, adopted the following resolution:

" 'Resolved, That in the opinion of this Board, the work (surveys and plans) has been done thoroughly and in a manner which meets its approval, and that the estimates and reports in which the results of these surveys and work have been embodied are entitled to the confidence of the people of the State of New York.'

"I voted for this resolution and still believe that the work can be done for the estimated amount approved therein, if carried on under efficient management."

William H. Burr, a professor of engineering in Columbia University and a member of the Isthmian Canal Commission, said at one of the hearings:

"The plans and estimates which are now before you were reached through a study by a body of engineers whose operations were characterized, I believe, by a degree of thoroughness and technical preparation which has never been excelled in the consideration of any similar engineering question. Careful surveys were made. The board of consulting engineers and its staff not only made its own examinations through this state, but had before it a great mass of surveys and an examination of the most thorough kind made by the United States Deep Waterways Board, a large portion of whose work lay in this state along the line of the proposed waterway."

Between the first and second hearings on the canal bill, on February 10, an Assembly resolution called upon the State Engineer to make a report to that body by March 1 in answer to certain questions contained in the resolution. This move was evidently an attempt by the enemies of the bill in part to delay action but more especially to get a revised estimate, probably not for the sake of accuracy but in the hope that the figures would be so large as to defeat the project by their very size. While waiting for this report canal men could do little but try to strengthen their organization and prepare public sentiment for whatever course might be necessary when the time for further action should come.

The canal bill as originally introduced in the Senate provided for deepening the Champlain canal to only seven feet, although in the Hudson river section locks of the 1,000-ton size were to take the place of existing structures. Naturally the people of that portion of the state were not satisfied and they zealously bestirred themselves to have the bill amended. They argued that there was fully as much reason for enlarging the Champlain branch to barge canal size as for increasing the Oswego canal to like dimensions. The tonnage records of the two waterways were compared -- decidedly to the advantage of the Champlain canal -- showing the tonnage of the latter during the preceding decade to be from 800,000 to 1,000,000 tons annually, while the Oswego had carried only 184,000 tons during the most prosperous year of the same decade and only 31,000 tons during the least prosperous year. The paper mills and the iron ore deposits in the Champlain region were cited as being of sufficient magnitude to demand a large canal. The prospect of Essex county iron ore being shipped in large quantities to the Buffalo steel works and thus becoming an important return cargo, was an argument of considerable weight.

On March 2 State Engineer Bond transmitted to the Legislature the report which he had made in response to the resolution of February 10. We do not need to concern ourselves with the detailed answers to each of the questions asked in the resolution; a grasp of the outstanding facts will suffice.

With reference to the accuracy of the original estimate Mr. Bond said: "The work throughout was organized in a systematic manner and carried to completion with the utmost care and thoroughness in regard to every detail, all questions as to location, method of construction, style of structures, classification of material and unit prices for estimates of cost being determined only after thorough investigation and discussion by the advisory board and myself.

"I have no hesitation, therefore, in asserting that the estimates of cost given in the barge canal report were as complete and accurate as any estimates ever prepared within the time allotted for a work of such magnitude, and that they were reliable estimates of the cost at that time for the improvement covered by the report, with the possible exception of the allowance for unforeseen contingencies and expenses.

"It is an undisputed fact, that during the past few years the prosperity of our country has resulted in an increase in the construction of public works of all descriptions, and in the development of native resources by private capital, creating such a demand for labor and material that both have advanced in price within the past two years; furthermore, the fact of the State enlisting in an enterprise of this magnitude would have a tendency to increase the price of labor and material entering into its construction.

"My answers to the questions contained in the resolution are made after a very thorough investigation and careful analysis of the conditions now prevailing."

In the form of a summary, Mr. Bond gave the following figures: The estimated cost of a 1,000 ton canal from Troy to Buffalo and from Three River Point to Oswego and of a seven-foot Champlain canal was $80,219,172. These figures are given in the report of the 1900 survey. If one desires to get at the component parts, he may take the net total of the route we described as line A, add to it the difference in cost between a 12-foot and a 9-foot Oswego canal, as shown in the description of line B, and subtract the value of abandoned Oswego canal lands. To the $80,219,172 there should be added $888,943. The cost of barge canal locks on the Champlain canal from Waterford to Northumberland, and $300,000, the estimate for constructing a lock and making necessary repairs to the Erie canal in the lumber district in Albany. Each of these pieces of work was included in the bill then pending and the additions made a total of $81,408,115. In rounded form this was the eighty-two millions of the bill.

The estimated increase due to advanced prices for labor and materials was $5,900,984 and this amount added made a total of $87,309,099. Lest the ten per cent allowed in the 1900 estimate for engineering and contingencies should not be enough to cover every unforeseen difficulty or emergency, Mr. Bond added five per cent more or $4,365,454. This brought the revised cost for the work included in the legislative bill to a total of $91,674,553.

We have seen that there was considerable public sentiment in favor of enlarging the Champlain canal to barge canal dimensions. In deference to this feeling Mr. Bond gratuitously included an estimate for this additional work ($7,355,965) and at the same time he inserted an item for a junction lock near Fort Bull ($129,168) and the cost of improving the Hudson river from Troy to Waterford and the Niagara river from Tonawanda to Buffalo ($1,403,307 on the basis of revised prices). The necessity for the junction lock had not been discovered at the time of the 1900 estimate; it would render available as a navigable feeder a long section of the existing Erie canal. It had been hoped that the Federal government would undertake the short stretches of improvement in the Hudson and Niagara rivers. Mr. Bond thought that their cost should be included in any appropriation for the canal, since the United States might decline to do the work. In that case all the vast improvement would be largely ineffectual, because there would be a barrier at each end of the canal and boats of deep draft could not pass beyond Waterford on the east nor beyond Tonawanda on the west. Adding these three items, the grand [original text has "grant".] total became $100,562,993.

This large increase in cost was what the opponents of the canal had hoped for. Their wish had come true, but it did not work out according to their expectations. Instead of being dismayed the friends of the project changed their plans to fit the new situation and pressed on with greater zeal.

After the presentation of the State Engineer's special report a few canal men met in conference. Abel E. Blackmar represented the New York city commercial organizations and George Clinton the up-state interests and with them met Henry W. Hill. These three considered the whole question with the utmost deliberation and reached the conclusion that the Champlain canal should be improved in the same manner as the Erie and Oswego branches and that additional funds should be provided for the project. Accordingly they changed the canal bill to meet these requirements and then submitted the amended bill to a larger conference, Senator George A. Davis and Assemblyman Charles F. Bostwick and James M. Graeff being called in and meeting with them on March 10.

In its amended form the bill carried an appropriation of $101,000,000. With the Champlain included, all of the canal advocates were united and there were not present thereafter in the Legislature of 1903 the divided interests which had characterized the sessions of 1901 and 1902, especially the latter year, when the alienation of the Oswego forces gave sufficient strength to the opposition to defeat the measure.

Before considering further the fortunes of the amended bill, let us turn for a few moments to two or three other subjects, and first we shall look at the counter projects brought forward by the adversaries in order to divert interest or directly to oppose the canal proposition.

On February 2 a concurrent resolution was introduced in the assembly which proposed to build a railway in the bed of the canal and to lease [original text has "least".] it upon certain terms. This resolution was never reported from the committee to which it was referred. Of a like nature was a proposition made by former State Senator Charles A. Stadler, who offered to form a corporation that would carry freight from Buffalo to New York in from a third to a half of the time required by canal boats and at a cost not more than by the existing canal. His plan was to build an electric or steam railway in the bed of the canal by means of which he expected to transport freight from Buffalo to Albany in 24 hours. Large boats were to be used between Albany and New York. This scheme was too visionary to give canal men much concern. Just how the new railroad was to do so much better than the existing well-equipped roads, in both rates and average time of shipment, was hard to explain.

On January 23 a concurrent resolution was introduced in the Senate proposing to amend the Constitution by striking out the section which prohibited the sale, lease or other disposal of the State canals. An attempt somewhat like this had been made to side-track canal legislation during the session of 1902. Like its predecessor of the year before this resolution too died in committee.

Another proposition was that presented to a joint meeting of the Senate and Assembly canal committees on March 11 by a company known as the International Towing and Power Company. It was a scheme of electric towage and the plan was to build on the outer side of the tow-path certain steel construction which should carry rails on which two electric tractors could run, being able to pass each other in opposite directions and so located as not to obstruct the tow-path, which might still be used by horses for hauling boats. The proponents of this scheme estimated that boats could be towed from Buffalo to Albany for 50 cents per ton and that the electric equipment would cost about $7,500,000.

As we have seen already, the Governor had suggested in his annual message of 1903 that electric propulsion might solve the canal problem. It is probable that his thought in the respect was influenced by a letter sent to him a few days before by ex-United States Senator Warner Miller, in which the idea was set forth in considerable detail.

It will be noticed of course that this proposition was in reality a substitute for the barge canal plan. It its success should prove as great as its advocates predicted, then there would be no need of a 1,000-ton canal. Moreover, it presupposed a tow-path or some other convenient place of which to build its tracks and in a river canalization, such as much of the proposed new canal was to be, a tow-path or other suitable place for tracks might often be lacking. It is probable, however, that as yet there was little general appreciation of what would be the nature of river canalization or of how large a proportion of the projected State canal system would be in river or lake channels. It is interesting to notice in passing that, when the debates were in progress on the canal bill a few days after this scheme was placed before the canal committees, Senator Davis, in controverting one of the chief claims for acceptance of this plan, the low cost of haulage, said that already boats were being towed by steam canal boats for 50 cents a ton from Buffalo to New York, 150 miles farther for the same amount of money.

Neither of the canal committees acted favorably upon this proposition, but in the autumn, just before election, as we shall see presently, a public demonstration of actual electric towing was given at Schenectady.

On the same day that the towage scheme was presented to the committees, Assemblyman Charles S. Plank of St. Lawrence county introduced a concurrent resolution which proposed to amend the Constitution so as to permit the reimposition of tolls on the State canals. The resolution was favorably reported from committee and passed the Assembly on April 8, with 76 votes in favor, a bare constitutional majority, and 50 votes opposed. It was then transmitted to the Senate, referred to the Judiciary committee, but never reported out.

This measure too had been suggested in the Governor's message. It was opposed by canal men at this time for two reason. In the first place probably most of them were of the opinion voiced in the resolution of the Canal Association of Greater New York that it "would mean a backward step and a regrettable reversion of the enlightened policy adopted by the people of the State in freeing the canals from any toll whatever." But more important at this particular crisis was the fact that the Constitution at that time prohibited the submission to the electorate at one and the same time both a bonding referendum and an amendment to the Constitution. This restriction, by the way, was eliminated by a constitutional amendment in 1905.

But of chief importance among the legislative measures opposed to the canal project was a bill introduced by Senator Merton E. Lewis which would authorize the Governor to appoint a commission to negotiate with the Federal government and inquire whether the United States would undertake the construction of a deep waterway between Lake Erie and the Hudson river and if so, upon what terms. Before introducing this bill Senator Lewis had presented a resolution of somewhat similar import, calling upon Congress to complete the surveys of deep waterways by an interior route and to include a full study of its possibilities for commercial and military uses and for the development of water-power. The resolution had been referred to the canal committee, where it was pigeon-holed. From its nature this bill was scarcely entitled to be the chief rival of the canal bill, but it assumed such position because its introducer came from the hotbed of anti-canal sentiment, Monroe country, and was most persistent in his opposition.

But not all the hostile activity was within the legislative halls. About the middle of March a colossal canal and water-power project was launched. Many prominent men were connected with it, but coming as it did just at this particular time and not being pushed later to fruition, one is forced to the conclusion that its purpose was primarily if not solely to divert support from the canal bill. The meeting from which this project sprang was held in the office of Andrew H. Green and a number of well-known New York city men were present. This meeting adopted a resolution calling for an international convention of all the peoples of North American and the purpose of this convention was to form an association to promote the construction of a continental system of deep waterways and a system of water-powers and also an irrigation system for the arid lands of the continent.

A partial idea of what the scheme involved is shown by a few words of one of the speakers at the meeting. He said, "Ten billions of dollars would construct a continental system of deep sea canals and create water power equal to fifty million horsepower ... At the rate of $23 a horse-power a year, fifty million horse-power would command a rental of one billion, one hundred and fifty million a year, or 11 1/2 per cent per year on the cost. On this basis the rental of water power would discharge the interest on the construction of the canals and water power and the cost of maintenance, and create a sinking fund for the discharge of the principal within fifty years. Competent authorities estimate the available water power on this continent to be equal to one hundred million horse-power. The system outlined would give to American vessels absolute control for all time to come of the foreign commerce of this continent without subsidies being granted them, and therefore save the two hundred million for subsidies proposed in the Hanna-Fry bill."

This meeting endorsed Senator Lewis' bill but evidently without definite knowledge of its contents since the language of the endorsement assumed that it asked "Congress to complete surveys for a canal thirty feet deep between the Great Lakes and Atlantic tidewater."

The immensity and boldness of this scheme and the prominence of the men connected with its conception gave the project wide publicity and it was endorsed by a portion of the press, probably without due deliberation.

It will be recalled that Andrew H. Green, one of the promoters of this project and in whose office the meeting was held, had been a member of the State Commerce Commission, the body appointed by Governor Black in 1898 to inquire into the causes of the decline of New York commerce. In the debate on the canal bill a few days after this meeting Senator Grady severely scored Mr. Green for his advocacy of the Lewis bill, attributing his action to railroad affiliations.

The press of the state took an active interest in the canal question during the whole of this year of 1903. Indeed the canal problem was a live subject for the press all through this period of agitation -- from the time when Governor Roosevelt appointed his committee which should formulate a State canal policy until the election of November, 1903, when the people went to the polls and gave their decision to build the 1000-ton canal.

The press of course was divided but the line of cleavage was unusual and so peculiar as to be difficult of explanation. In general the New York city and Buffalo papers were favorable while those of territories remote from the canals were opposed, but strangely most of the large cities on the canals were against the proposition. Rochester was almost solidly opposed. Syracuse, Utica, Albany and Troy were largely against it. The smaller canal cities, Rome, Oswego, Lockport, Tonawanda and Niagara Falls, were in favor of the new canal. So were Plattsburg and Dunkirk. Poughkeepsie, Newburgh, Binghamton, Elmira and Watertown were of the opposition. Whether these papers simply reflected the sentiment of their respective communities or were chiefly instrumental in creating it, cannot definitely be known. We are inclined to the latter opinion in many cases. Of the technical press the Engineering News was strong in its opposition. But such had been its customary attitude toward the New York State canals for many years. The Journal of Commerce, New York's great business daily, on the other had was equally strong in its advocacy of the canal cause.

Among the arguments of the opposition the ship canal had a large place and much publicity was given to the idea that the Federal government should construct this larger waterway. The report of the Deep Waterways survey was cited and reviewed as well as other ship canal reports. It will be recalled that Major Symons said the Deep Waterways report fell flat upon its presentation because contemporaneous investigation had shown the question of relative economy and efficiency to be largely in favor of a barge rather than a ship canal.

Another form of opposition was the anti-canal propaganda placed in railway stations in the shape of circulars and pamphlets on such topics as the "Decline in Canal Traffic," "What the Railroads Have Accomplished" and "Railroads Supersede Canals." This form of attack by the railroads had the virtue of at least being open, and this cannot be said of all their acts, for canal advocates charge that more often than not the methods of these particular enemies of the canals are insidious.

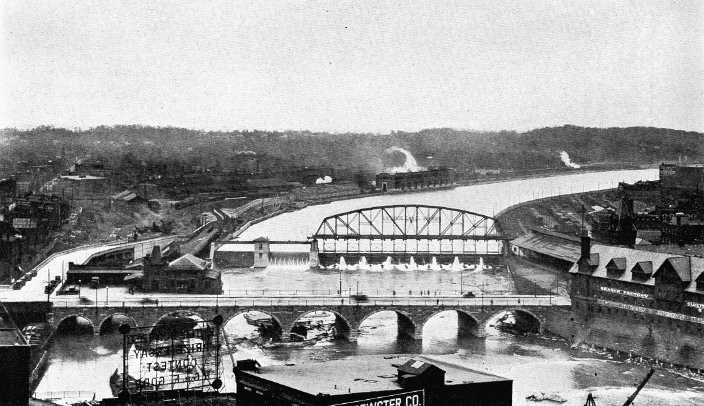

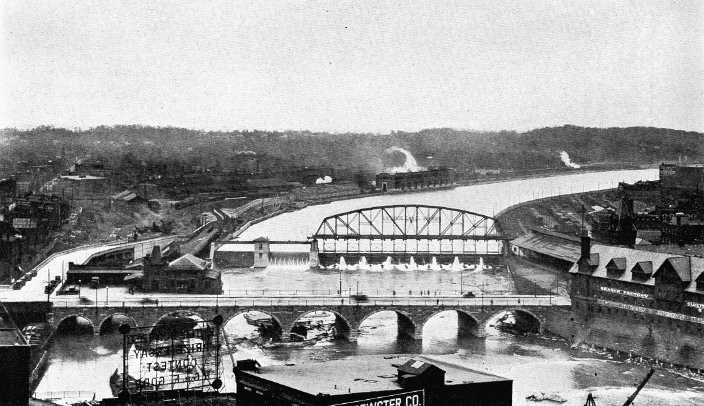

Rochester harbor, in the heart of the city, connected by a spur in the Genesee river with the main canal, which avoids the city. Pool level maintained by a movable dam of combined bridge and submersible sector types. River lined by high walls on both sides. Terminal warehouses, one brick and one frame, appear above the dam; a viaduct approach to the terminal at the extreme left.

There was also an opposition which arose from those who professedly and doubtless really wanted canal improvement but were restrained from favoring the particular form of improvement described in the pending bill because of certain local changes which would result -- changes in many instances which would in some way affect them or their interests. Of such character was an objection to the canalization of the Mohawk river which was given rather wide publicity by means of circulars sent out to the public. We quote two of the ten results which according to this circular would follow the carrying out of such a scheme, but the two we are choosing attacked the project on purely engineering grounds and were absurd when the circular was written. In the light of what has now been done even the layman can perceive the absurdity.

"The canalizing of the Mohawk river," reads the circular, "would change and contract its present current and cause it to overflow the New York Central railroad and carry away their tracks, culverts and bridges. When the river breaks up in the spring and often also during the winter, it overflows its banks and the ice rushes down with great force which would greatly damage if not totally destroy all of the permanent structures of the canalized river.

"The idea of canalizing the historic Mohawk river sounds well and may be captivating to the minds of many, but when the matter is reasoned out in all its bearings and stripped of its romance it becomes an impracticability if not an impossibility."

We have been considering for some little time measures and arguments which were chiefly opposed to the canal bill, but both sides were equally active. While the legislative contest was going on, organizations in favor of the canals were effected in many parts of the state and representatives were sent to Albany to appear at the various hearings. Also meetings were held and resolutions were adopted. The organizations which had backed canal agitation through all these latter years kept constantly in close touch with the legislative situation. Another organization, which we have not mentioned previously but which was older than any of the others and had consistently supported every measure for canal improvement since the original State canal was begun and had even favored a proposition to connect the Great Lakes by canal with the Atlantic ocean as early as 1784, the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York, adopted a strong canal resolution and sent copies of it to the Governor and the members of the Legislature. Throughout its long history this organization has counted among its members some of the most eminent men of the state and nation.

A piece of pro-canal propaganda put out by the New York men during this time was known as the "Canal Primer," or giving it its more comprehensive title, "The Canal System of New York State; What it was; What it is; What it has done for the Commonwealth and the Nation, and what benefits the Empire State will derive from the proposed improvements." In the form of questions and answers this pamphlet covered in a fairly complete manner the field of the origin, development and influence of the canal system of the state.

As we return now to the canal bill and trace its further course through the Legislature we can do no better than to follow closely the written account of one who was in the thick of this legislative battle and to whose zeal and watchfulness is due much if not the greater portion of the credit for the success of the canal issue. And we may profitably quote with considerable freedom the exact wording of this account . It is a part of Senator Henry W. Hill's Waterways and Canal Construction in New York State.

"Notwithstanding the declaration in party platforms," says Senator Hill, speaking of this particular canal bill, "a majority of the Republican leaders in both branches of the Legislature were opposed to its passage. ... The opposition had left nothing undone to dissuade legislators from voting for it. It was characterized as a colossal scheme, wholly unwarranted in this age when canals were fast becoming a thing of the past; and it was declared that in the march of civilization waterways were giving way to railroads, and a mule on the towpath was no longer a competitor of the colossal locomotive hauling from 50 to 75 loaded cars of 80,000 pounds capacity. Sarcasm, repartee and denunciation were freely indulged in by the press and in the debates on the measure."

The canal bill was reported out of the Senate canal committee on March 12, having been amended so as to include the Champlain canal and carrying the appropriation of $101,000,000. On March 17 the Lewis bill was reported. This was the bill, it will be recalled, which provided for the appointment of a commission to negotiate with the Federal authorities relative to the construction of a ship canal across New York state. Senator Davis, the introducer of the canal bill, was successful in securing a position on the calendar for his bill ahead of the Lewis bill and it was advanced without debate to the third reading on March 17, with the understanding that it would be debated on the third reading and such amendments would be offered then as might have been offered in the Committee of the Whole.

Another element entering into the contest was the position taken by the two Republican senators from Erie county, Senators Hill and Davis, with reference to the excise and mortgage tax bills, which the Republican majority had planned to pass. These men insisted that the election pledge of the party be redeemed and the canal proposition be carried through before they would support these other bills. Since their votes were necessary for the passage of these measures, they had the whip-hand.

The canal referendum measure was reached on the Senate calendar on March 24 at 11:45 A.M. Thereupon Senator Lewis moved that the bill be recommitted to the canal committee with instructions that it be reported at once, amended by striking out all after the enacting clause and inserting in lieu thereof his bill authorizing the negotiation with the United States Government. In support of his motion Senator Lewis made an elaborate speech against the canal bill, in the course of which he read resolutions purporting to have been signed by more than a hundred distinguished New Yorkers, endorsing his measure. The attitude of these signers was questioned and in reply to telegrams of inquiry replies were received from some of them before the vote was taken, stating that they had signed under misapprehension and were really in favor of the canal referendum.

We do not need to follow the debates nor the many proposed amendments. The contest lasted for hours. There is only one feature among those brought out in the speeches that we care to mention here and this is a statement made by Senator Davis as to why Buffalo was so deeply interested in canal improvement. We speak of it simply because it refutes a rather prevalent idea in regard to Buffalo's attitude.

This idea, as Senator Davis said, was that Buffalo wanted the handling of grain transfer. But this had never amounted to more than 50 cents a ton and the traffic had dwindled to almost nothing. This was not the incentive which actuated Buffalo; rather it was the prospect which a large canal offered of making that city an iron and steel center capable of delivering its products at tidewater for a lower price than could be done from any other point on the continent or perhaps the world.

"Therefore," said Senator Davis, if we may quote a sentence here and there from his speech, "instead of the old grain traffic paying us never over 50 cents per ton, we propose to foster an industry that will pay to our people from $5 to $20 per ton to be expended in labor. This means an enormous increase in population among the Niagara frontier. We propose making Buffalo the greatest manufacturing center on the lakes. At the same time we will be able to furnish all kinds of iron and steel material to all local points through the state and to New York city at prices that cannot be equalled anywhere in the country. This will culminate in manufacturing all along the canal, and will in a few years make the canal, and the river as well, the greatest manufacturing sections in the world. Buffalo has practically forgotten the grain traffic in view of the bright future opening up in other lines."

After this short digression we return to the battle being waged in the Senate chamber on that twenty-fourth day of March, 1903, and for the remainder of the chapter we shall quote directly and at considerable length from Senator Hill's account, selecting passages from his Waterways and Canal Construction in New York State.

"The obstacles interposed to the passage of the measure were such as to call for the utmost skill on the part of its friends to avert them. Direct and insidious attacks by way of proposed amendments were made upon it. Fortunately, the Hon. Thomas F. Grady, the most skilled parliamentarian then in the Senate, was on the alert to repel every move made to check the progress of the measure. He was in the Legislature from 1877 to 1889, and had been in the Senate continuously from 1896 to the time under notice. He was then leader of the minority, and exerted a powerful influence upon his Democratic colleagues in the Senate. During the debates, which continued five and a half hours, he received a special message from Charles F. Murphy, the leader of Tammany Hall, which read as follows:

"'My dear Senator: I desire to again remind you of the vital importance of doing everything in your power towards the passage of the canal bill, framed by the Canal Association of Greater New York. Aside from other considerations what should induce our support of this measure, is the fact that among the many distinguished citizens of our city who are agitating its passage, are many good and valued friends of the organization.'

"Senator Grady was already earnest in his support of the measure, but the impartation of this information to the other legislative members of Tammany Hall had a most salutary effect upon their attitude toward the measure."

"No parliamentarian ever exhibited greater tact during the entire day, or more materially aided in the passage of a great measure than did Senator Grady on that occasion. His steadfastness and fidelity to all canal measures -- and there have been many, in support of which he has successfully led a solid Democratic minority -- entitle him to the lasting gratitude and grateful remembrance of all the people interested in the commercial development of the State."

"During the debate on this measure the Senate galleries were thronged, and an intense interest prevailed. Those of us in charge of the measure were keenly apprehensive lest there be some wavering in the ranks of its supporters, or through some other parliamentary attack of its opponents, that it fail of passage."

"On the final roll-call, after all adverse amendments had been voted down, the canal referendum measure received the affirmative votes of 32 Senators and there were 14 votes against the measure on its final passage."

"In some respects the contest in the Senate was one of the most dramatic ever witnessed. It was the culmination of a movement starting with the abolition of tolls in 1882, and then for the enlargement of locks and deepening of the prism; thereafter for the improvement known as the Seymour-Adams plan; and finally the projection of the barge canal proposition. Such a movement extending over a period of two decades very naturally aroused deep interest, and its issue was fraught with extraordinary consequences to the commerce of the State.

"Parliamentary contests usually involve matters that are largely temporal in character, which may be modified from year to year; but this project was fraught with momentous consequences to the State in that if it passed the Legislature and were approved by the people, it authorized a bond issue of one hundred and one millions, running over a period of eighteen years, which under a constitutional amendment then pending was likely to be extended over a period of fifty years. It so far transcended in importance all ordinary parliamentary contests that it called forth the best efforts of all who had any part in it, either in or out of the Legislature.

"During the long and strenuous debate the friends of the measure were intense in their advocacy of it and were called upon to defend its engineering, its fiscal and constitutional provisions, all of which were assailed by the opponents, who were equally resolute in their attacks upon it. It was the largest measure ever submitted to or considered by a legislative body in this country, and naturally aroused the deepest interest.

"The pro-canal press of the State was jubilant over the passage of the canal measure and spoke in complimentary terms of Senators Davis, Hill, Grady and Green, upon whom largely rested the burden of carrying the measure through the Senate. Much credit is also due to the other senators who, although less conspicuous in the debates, but their votes made it possible for the canal bill to pass the Senate by a large majority vote.

"After the canal bill had passed the Senate, it was transmitted to the Assembly on March 25th, and a motion was made to advance it to the order of second reading; whereupon several amendments were offered by Assemblymen George M. Palmer, Edwin A. Merritt, John T. Dooling, John Pallace, Jr., William V. Cooke, Daniel W. Moran, Olin T. Nye, George H. Whitney, Charles S. Plank and Samuel Fowler. It was evident that the bill had encountered very fierce opposition in that body. Assemblyman John McKeown of Brooklyn immediately moved a call of the House, which was had. Assemblyman Palmer moved that the bill with the amendments be made a special order on second and third reading for Tuesday, March 31st, and that motion was determined in the negative. Thereupon Assemblymen Jean L. Burnett and Fred W. Hammond moved further amendments to the bill and after some discussion of the motion of Assemblyman Fowler, the bill, together with all amendments, was made a special order on second and third reading, for Thursday, March 26th, immediately after reading the journal.

"On the day named, when the canal bill was reached on the calendar, Assemblyman Palmer spoke in favor of his amendments; and, after a discussion by other members of the Assembly, including Assemblyman Charles F. Bostwick, of New York, the introducer of the measure, Assemblymen Robert Lynn Cox of Erie, James T. Rogers of Broome, and others, all of the Palmer amendments were voted down, as were also all other amendments to the measure that had been proposed. The opposition, however, of Assemblymen Palmer, Moran and Pallace was continued down to the final vote on the measure.

"Several Republican members who had offered amendments to the bill withdrew them during the discussion, and before the final vote Assemblyman Palmer reintroduced the same amendments and insisted on a roll call on each amendment introduced by him. The roll call occupied two hours of the time of the Assembly and all of his amendments were voted down.

"Assemblyman Rogers, the leader of the Assembly, in withdrawing his amendment, stated that he considered that the canal advocates were entitled to have the referendum measure submitted to the people in the form in which they had framed it, and advised all Republicans to vote down the various amendments that had been proposed. Other assemblymen took a similar position; and after a discussion running through the entire day, far into the evening, the bill passed the Assembly by 87 affirmative votes to 55 votes against it.

"The bill had been reached at 11:30 o'clock in the morning. Thirty-six amendments were offered to it altogether in the Assembly and most of them were debated until 6 P.M., when voting began on the amendments and continued for two hours.

"Assemblyman Cox made a strong speech on the bill, as did Assemblymen Charles W. Hinson and Anthony F. Burke, all of Erie county. The burden of the debate, however, fell upon Assemblyman Charles F. Bostwick, the introducer of the measure, who had given the bill much study during the legislative session.

"At the conclusion of the vote in the assembly, George H. Raymond of the Merchant's Exchange of Buffalo, remarked: 'Today has witnessed the culmination of eight years of labor on the part of the business interests of the State to secure for all time to our people the enjoyment of a free waterway between the Great Lakes and the sea. ... We are now to undertake the greatest public work ever proposed in this country, and the results will be beyond the wildest dreams of its friends.'

"On April 7th, at 11:35 A.M., Governor Odell gave his official approval to the canal referendum measure in the presence of Senator George A. Davis and myself, and Messrs. G.K. Clark, Jr., John D. Trenor of the Greater New York Canal Association, and S.C. Mead, secretary of the Merchant's Association of New York; and it became chapter 147 of the laws of 1903 of New York."

http://www.eriecanal.org/Texts/Whitford/1921/chap05.html