Canal Completed in Time for War Use -- High Hope of Result of Government Control -- Call for State Canal Convention -- Marshaling National Transportation Media -- Government Investigates Barge Canal -- Action by Canal Convention -- Delays -- Government Assumes Control -- Announcement Hailed with Joy -- Disappointment Follows -- Nature of Federal Control -- Review of Situation by Mr. Gardner -- Interview with Director General of Railroads -- Unsatisfactory Results -- Superintendent Wotherspoon's View of Federal Control -- Other Views -- Clamor for Return of Canal after War -- Official Opinions on Effect of Continued Control -- Federal Domination Somewhat Lessened -- Control Transferred to Secretary of War -- Opinion as to Reason for Action -- State Attempts to End Control -- Hearings on Resolution to Return Canal -- Government Operation Continued Another Year -- Résumé of Federal Control and Arraignment for Its Inefficiency.

We have seen how by almost superhuman efforts the State Engineer and others of his department, assisted by the Superintendent of Public Works, the contractors and their many workmen, had succeeded in opening a channel of full depth throughout the entire length of the barge canal for the beginning of the 1918 navigation season. It was a magnificent spectacle. Driven by the spur of unselfish patriotism each had done his bit to complete the canal, and now it was ready to serve the Federal government in a great emergency, even at the time of its supremest need; it could relieve a congestion in the transportation of war munitions and equally essential industrial commodities that was becoming well-nigh perilous.

A few weeks before the canal was finished it had been announced that the waterways of the country had been taken over by the Federal authorities and would be operated, together with the railways, as emergent war transportation media. With considerable self-satisfaction, therefore, the people of the state, and especially those who had labored so hard to accomplish this result, congratulated themselves that they had thus been permitted to render no small service for their country, even deeming the opportune completion of the Barge canal at this time almost providential. If this were all of the story, we also could contemplate the event with equal satisfaction, but the sequel presents a different tale. From the magnificent picture of exalted selflessness we turn, if we may credit the evidence, to one of sordid selfishness. We might almost consider the denouement amusing, were it not so serious. Perhaps it is indeed a rare joke to the opponents of the canal; certainly not to its friends. The account of Government control of New York waterways surely forms an interesting chapter in Barge canal history but in its ultimate outcome it is one which cannot be recalled with any complacency by canal supporters. Urged upon the Federal authorities through a high sense of patriotic duty, this control fell to a base misuse of authority for selfish ends; acclaimed as a means whereby years could be saved in building up a Barge canal traffic, it proved in the end to be almost a death blow to any hope of a successful traffic on the new waterway.

But to follow the history of this movement we must turn back to the early days of America's entrance into the World war. The first concerted public action in this matter resulted from the calling of what was termed, for the want of a better name, a State Canal Convention. This body met in Albany on August 1, 1917, its purpose, according to the language of the summons, being "to consider and devise measures to bring the Barge canal to perform the world service of which it is capable, to bring its great value as a means of transportation to the immediate attention of the national government, and secure the coöperation of the Governor and the Legislature of this state for the achievement of these purposes." The initiative in issuing this call was taken by Frank S. Gardner, secretary of the New York Board of Trade and Transportation, but in reality the convention had been for some time in the making and was but the natural outcome of the unusual situation then confronting the country.

Prior to this convention, however, the subject had received much thought and attention and various activities related to it had been started. When the country had passed from a state of neutrality to one of belligerency it began the mighty task of marshaling its resources, a task made greater by the very abundance and diversity of those resources, and among the multitudinous problems it encountered, that of transportation permeated them all. Those in Washington who had to do with these matters appreciated the important place waterways held in any plan to utilize to the full the transportation agencies of the country and accordingly the Department of Commerce, after a quick survey of the situation under the personal direction of Secretary Redfield, had inaugurated a campaign for bringing about the use of waterways, appealing to the country for a full utilization of existing facilities and urging upon citizens and communities the rehabilitation of worn-out and the building of new equipment. Then a bureau of inland waterways was organized in the Department of Commerce, with a transportation expert at its head. This department was working in close coöperation with the National Council of Defense, which also had appointed a special committee on waterways. In addition State Engineer Williams and Superintendent of Public Works Wotherspoon tendered to the Government the canal as it then was and offered their own services and those of the State to hasten its completion as soon as was humanly possible. Because of his former army position and acquaintances General Wotherspoon's words carried especial weight. Also George Clinton brought the matter to President Wilson's attention and was personally assured by the President that he would place the subject before the proper authorities with his full approval.

This agitation brought the Barge canal prominently before the Washington authorities and as a result the National Council of Defense appointed a subcommittee to tour New York state and investigate the canals. The report of these men was not made public, but it is generally thought that their impressions were not altogether favorable, at least so far as he immediate use of the canal was concerned. At that time, it will be recalled, certain stretches of the new canal were still to be completed, new shipping had not been built and the supply of old boats was deplorably inadequate. General Wotherspoon said that the two men constituting the committee to tour the state came in response to his correspondence with General William M. Black, the chairman of the committee on Inland Water Transportation, and were accompanied on their trip by members of his department, also that they expressed themselves satisfied that the canal itself possessed all the physical and economical elements required for success, but that, as was obvious to everybody, the boats to make possible this success were lacking.

There was an apparent disposition on the part of all concerned, however, to utilize New York's waterway, but in spite of all that had been done, tangible results did not follow, either in using the canal or in preparing to use it, and the canal enthusiasts of the state grew restive. Believing profoundly that the Barge canal would be New York's greatest war contribution to the nation, they were impatient of any delay in its service, and so the convention of August 1, 1917, was called.

This convention was attended by representatives of the State Waterways Association and many civic bodies, also the mayors of cities and numerous prominent persons. Its action took the form of petitioning the Legislature, then convened in extraordinary session, to memorialize the President of the United States, the National Council of Defense, the Secretary of War, the Secretary of Commerce and the Committee on Inland Waterways, calling attention to the availability of the New York canals and urging their use to the fullest possible extent. The backing sought by this convention was obtained. The Canal Board by action of August 21 endorsed the movement; the Legislature three days later memorialized the Federal authorities and Governor Whitman formally transmitted the documents to President Wilson and other officials at Washington.

But it was several months before any definite action was taken. Meantime the canal was nearing completion. On January 31, 1918, State Engineer Williams appeared personally before the Senate Committee on Commerce, in the course of its investigation of matters connected with the building of merchant vessels under the direction of Shipping Board Emergency Fleet Corporation, and informed the members that the Barge canal would be open throughout its entire length the following spring, but that boats for use upon it would be sadly lacking, and moreover that it was virtually impossible for private enterprise to construct boats, and if the canal was to be utilized as a military adjunct, it became the duty of the Federal authorities either to build the floating equipment or to assist by some method in providing it. Also various plans were submitted to the Government by individuals and these generally involved financial aid to private canal transportation companies, which it was proposed to organize.

Finally, however, -- on April 10, 1918, -- members of the inland waterways committee appointed by the director general of railroads, Mr. McAdoo, appeared before the Canal Board and requested the coöperation of the authorities charged with administering State canal affairs in an effort to bring about a coördination in the use of the railroads and the State canal system during the period of the war. This was just what canal men had been striving for and Canal Board gladly assented. In the words of its resolution it "assured the director general that the officials of the State of New York in charge of the operation and maintenance of the canals of the State were ready, willing and anxious to coöperate with the director general in the utilization of the canals to the fullest possible extent." A special committee of the Canal Board, in company with the Federal committee, at once waited upon the Governor and an expression of the willingness of the State to coöperate with the National government in its plans was formally transmitted by him to the Washington authorities. On April 18 formal announcement was made by the director general that he would secure boats and establish an operating organization to utilize the State canals.

This announcement was hailed with joy. Some persons went so far as to say that this use of the new waterway in the time of the nation's direst need would justify the cost of its building even if it were never used afterward. Canal advocates, besides being pleased because they seemed to have builded better than they knew, saw in the action of the Government the promise of an unexpected ally, nothing less than that which appeared likely to accomplish in months what it would naturally have taken years to bring about. They had realized what a herculean task was before the canal in the building up of a traffic, how only by years of unabating toil could commerce accustomed to other lines be diverted to the canal. Here was the hope that by what may be considered artificial means this metamorphosis was to be attained. Here was a supreme power, having absolute authority over all transportation, that at will could route traffic where it pleased. The usual courses were choked and it seemed inevitable that the canal would get a large share of this traffic.

But their dreams were not to come true. Neither were the expectations of the people of the state at large to be realized concerning their supposed munificent contribution to the country's emergent need. Gradually it became evident that these fair hopes were doomed to disappointment. First came the announcement that canal and rail rates were to be equal. Later this ruling was changed and canal rates had a twenty per cent differential. The official announcement that no private lines would be allowed on the canal elicited such a storm of protest that it was followed by a disavowal of any intent to forbid private operation of boats. To state in a word the history of Government control over New York canals it may be said that apparently the transportation lines were operated solely for the benefit of the railroads and that private companies were in effect excluded from the canal because no one under existing circumstances would compete with the Federal government. Canal men believe that the railroad interests dominating the Government control deliberately misused their temporary authority to injure the canal, but of course positive evidence of such purpose is lacking. The retention of the waterways, however, after the railways were turned back to their owners, seems to indicate that some influence ill-disposed toward canals was working. But we shall let the men who were in close touch with the whole situation tell the story in their own words.

First, however, it may be well to explain the nature of the Federal operation of the New York canals. People in general had little understanding as to what had actually taken place. The State did not lose possession of its canals; under the Constitution it cannot. Moreover it still continued to maintain and operate both the channel itself and its structures, just as it has always done, bearing all the expense of this operation. The State's position in regard to its canals was scarcely changed in any particular. Unlike the administration of the railroads the Federal government did not guarantee the payment of dividends nor provide for the upkeep of the property, nor in fact did it assume any financial obligation whatsoever connected directly with the canal itself. This fact should be remembered for a better appreciation of the Government's attitude toward the canal, as it is revealed by the men we are about to quote. What the Government really did was something which the State had never done, namely, to take over control, either directly or indirectly, of the floating equipment on the canal. Its position is somewhat analogous to that of a large transportation company which was building boats and operating them on a State-owned canal. It obtained control of a large proportion of the boats that had been in use during recent years and built some new boats. The Government, however, was much more than a mere transportation company, for it stood ready to control all shipping on the canal, assuming the right under authority of Congress to commandeer any and all boats doing business on the waterway and even to direct the activities of those in did not commandeer.

At the convention of the State Waterways Association on November 7, 1918, Frank S. Gardner, the man who had conceived the idea of the special convention of August 1, 1917, told of an interview certain New York representatives had with the director general of railroads. What he said is enlightening. It runs as follows:

"Mr. President and Gentlemen: At the request of Senator Hill, I have put on paper a few facts regarding our interview with Mr. McAdoo in Washington on the 25th of last month, what he said, and the result of his policies.

"The conditions existing upon the canals of the state which have been created by the policy of the Railroad Administration constitute a cause for much concern to the state and to all her business interests, and I venture to suggest that this Association at this time consider what steps should be taken to protect our business interests under the circumstances.

"Most of the gentlemen here present are aware of the fact that the New York State Barge Canal Conference met at Albany on August 1, 1917, and petitioned the New York State Legislature, then in extra session, to memorialize the officials of the United States Government and to urge them to make the fullest possible use of our state canals for transporting to the seaboard the food and military supplies to maintain our armies, and the food and other supplies for the armies and people of our Allies abroad; that the New York Legislature on August 24, 1917, did so memorialize the Federal Government and that such memorial was formally transmitted by Governor Whitman to President Wilson and other principal officials.

"Some eight months elapsed without any definite action in the matter by the United States Government. At the end of that time the Federal Railroad Administration announced that it had taken over control of navigation upon the canals of this state. The general public were in quite a dilemma as to what actually had been done and the officials themselves of the Railroad Administration appeared to be in some confusion, because they and their representatives made announcements which were generally understood to extend Railroad Administration control over all operations of all boats upon our canals.

"Shortly prior to June 15, 1918, the Railroad Administration announced that canal and rail rates would be upon a parity, and that the usual differential would not be allowed to freight via the canals.

"This order as issued was understood as applying to all freight carried by canal whether in boats operated by the Railroad Administration or by private individuals and corporations. In fact a circular issuing from the office in New York of the Canal Section of the Railroad Administration announced that no private canal lines would be permitted to carry freight upon the canals for their own account. This caused consternation among shippers and carriers by canal and was regarded as a calamity to this state and all of its business interests.

"The situation into which our canals were thus apparently brought was the subject of unfavorable criticism by a number of influential organizations and by many important newspapers, and soon elicited from the Chairman of the Canal Section a disavowal of any purpose to forbid private operation of boats.

"This public discussion was followed by announcement by the Railroad Administration, published June 23d, that the rail rates would be advanced 25 per cent on June 25th, but that the canal rates would be allowed to remain at the then existing rail rates. This was a partial recognition of the natural difference in rates between rail and canal and was made after a call had been issued for a meeting of the New York State Barge Canal Conference to be held in Albany on June 16, 1918, to consider the situation.

"The Barge Canal Conference on June 16, after full consideration adopted an address to the Director General of Railroads, expressing the views of the Conference, and appointed a committee to submit such views to the Director General in person. It also appointed a special committee of traffic men to prepare a statement showing the relation between rates by the canals and by the railroads, and the rates which should be charged upon them, respectively, and the reasons for the substantial difference between them.

"The Committee of the Conference was unable to get an appointment with Mr. McAdoo until the 24th of last month, nearly four months elapsing, and they then proceeded to Washington. On Friday morning, October 25th, they met Mr. McAdoo, who attended by Judge Edward Chamber, Director of Traffic, Mr. Carl Gray, Director of Operation, and Mr. Oscar A. Price, all of the Railroad Administration.

"It was my privilege to be present at this interview, and several gentlemen who are attending your meeting today were also there. I listened with much interest and attention to what Mr. McAdoo had to say. The interview covered fully an hour and a half, and while much pleased with Mr. McAdoo's courtesy, patience and frankness, I was soon impressed with the fact that a most grievous mistake had been made by our Barge Canal Conference on August 1, 1917, in appealing to the Federal Government to make use of our canals. In saying this I must confess that I had a part in bringing about the action of August 1, 1917, which to me now appears to have been so fatal to the very object we desired to accomplish, viz.: to induce the Federal Government to take such measures as would result in the greatest possible use of our canals.

"I am now convinced, from what Mr. McAdoo said to us on October 25th, that the measures he has adopted and the policies he proclaims, will not result in the greatest use of our canals, but will wholly subordinate their use to the enhancing of railroad revenues and the non-use of the canals wherever their use can be avoided.

"With much frankness Mr. McAdoo assured us that boats when operated by private individuals or corporations would not be interfered with; that they could charge any rates they saw fit, and he was willing to guarantee that private boats would not be commandeered by the Railroad Administration, but as to this he could not speak for the Army or the Navy.

"In response to and inquiry referring to building new boats for private operation he said: 'If so much steel as would be needed to make a tenpenny nail -- and it is just about as close as that -- should be needed to carry on the war it would have to be so used and could not be devoted to canal boats.'

"It was also brought out that the Railroad Administration had started practically all the usable existing boats, and as the discussion proceeded it was quite clear that, notwithstanding the promises of non-interference of private operation of boats, the obstacles created to private operation were insurmountable.

"He said that a number of steel boats and a number of concrete boats were being constructed for the Railroad Administration.

"He asserted that the Railroad Administration has full power to route all freight by such lines as it thinks proper, and, upon inquiry, defended the policy of sending boats empty from New York to Buffalo on the ground that to send them loaded, 'at any old rate,' would reduce the railroad revenues. He said he could not approve of the boats created by the Government taking rates so low as to reduce the revenues of the railroads.

"Mr. McAdoo was asked if the Railroad Administration would be willing to make arrangements by which freight could be shipped to interior points in the West or from such points to the East, via rail and canal on through shipment and through bill of lading, giving the freight the advantage of the lower canal rates for the water portion of the carry.

"Mr. McAdoo said he did not think the Administration could do that because it would destroy their rail rates.

"This being the policy of the Railroad Administration, for which Mr. McAdoo declared himself alone to be responsible, will result in subordinating the canals to the railroad policy and will keep canal rates upon an approximate parity with rail rates, and he further plainly intimated that, having the power to route all freight, it will not be routed via the canal so long as the railroads can carry it. This, manifestly, must dispel all hope for the greatest possible use of the canals in the near future or during the continuance of Railroad Administration control of navigation on the canals.

"In conclusion, therefore, I repeat what I said in the beginning. The conditions existing upon the canals of this state which have been created by the policy of the Railroad Administration, constitute a cause for much concern to the state and to all of her business interests, and I venture to suggest that this Association, at this time, consider what steps should be taken to protect our business interests under the circumstances." 1

General Wotherspoon spoke at this same convention. The following words of his concerning Federal control are worth quoting:

"If any discussion were to be had as the disadvantages of the Federal control of canal freight, I would mention particularly the fact that the entrance of private capital into the field was absolutely discouraged. Three reasons have been advanced for this condition: First, the available Erie Canal boating equipment had been secured by the Government, and individuals could not accomplish the construction of new craft in time to be used the present year, since no materials for boat construction could be obtained without the greatest difficulty.

"Second. The understanding the private companies, if formed would have been compelled to operate under the supervision of the United States Railroad Administration, with no guarantee that their boats would not be requisitioned by the Government for other purposes.

"Third. That no private companies cared to compete with the Federal authorities in canal business.

"It is true, of course, that so far as the second and third reasons are concerned, about mid-summer an effort was made by the National Government to relieve the impression that the field was not open also to independent carriers, but such announcements came too late for practical purposes during the present year at least. In this connection it is significant to note that from the day the announcement was made that the movement of canal freight would be controlled by the Federal authorities, I have had scarcely a single call from any interest having in mind the formation of a private boat company, while previous to that date hardly a day passed by the subject was discussed with one or more callers." 2

In General Wotherspoon's opinion, however, the advantages of Government control during the first year of the new canal's operation outweighed the disadvantages. It was of the utmost benefit to the waterway during this season, he declared, that traffic should be under a centralized control, rather than that boats should be operated as individual units, as had been the general practice theretofore, and also that such service as was furnished should have been rendered by a dependable and responsible carrier. He considered, moreover, that the general merchandise service which the railroad administration had inaugurated at his suggestion was a long step toward bringing home to the citizens of the state the advantages of waterway transportation. Also in 1918 for the first time rates had been stabilized by publication in tariff form. He doubted whether the transportation of freight on a large scale could have been accomplished during the year without Federal control. As a matter of fact there was a complete absence of prospective carriers in sufficient numbers a year earlier. The field was carefully investigated at that time by the subcommittee of the National Council of Defense, as we have already seen, and while several companies then claimed a corporate existence none was ready actually to engage in business without considerable financial aid from the Government.

Although General Wotherspoon held this favorable opinion of the season's traffic, at the same time he advocated that Federal control should continue after the close of the war no longer than would be required to adjust business conditions on a peace basis.

A view of the situation which existed subsequent to the war is found in the following quotation. It comes from a paper read before the State Waterways Association on November 20, 1919, by Edward T. Cushing, of the New York Produce Exchange.

"It is for the interest of the government," he said, "to kill any competition of the canal with the railroads, for even if the railroads were returned to their owners, the government would still guarantee their earnings. No sane man will compete with the Federal Government. What an object lesson in paternalism! The fear of it is today paralyzing the operation of the greatest inland waterway in the world. The stake -- one hundred and fifty million dollars of the people's money invested in the Barge canal; the contestants -- the United Railroads, backed by the Federal government, against the people of the state of New York." 3

Another quotation, this time from an address made by Edward S. Walsh, Superintendent of Public Works in 1919 and 1920, before the State Waterways Association at this same 1919 convention.

"I made every effort," said Mr. Walsh, "to persuade the United States Grain Corporation to utilize the canal facilities, but without success. Explanation for the failure of the Grain Corporation to employ the water route, particularly when it was announced broadcast throughout the country that a serious car shortage was impending, did not explain. I, therefore, am forced to the conclusion that the routing of grain from Buffalo by rail to the utter exclusion of the canal, was either the result of poor business judgment or discrimination of the rankest nature against the waterways of the state." 4

With the war at an end and no longer any reason existing for continuing Federal control, State officials and canal advocates began clamoring for the Government to relinquish all authority over canal traffic and to cease operating its boats. But again they were doomed to disappointment and for two seasons more the United States authorities retained their hold on the canal.

Of the effect of this experience State Engineer Williams says in his 1920 annual report, "The designers of the canal had contemplated that it could not be expected to reach its maximum carrying capacity within a period of less than five years and this conclusion was arrived at without foreseeing the conditions of war, which have completely upset the ordinary and usual economic development that could have been reasonably looked forward to. In view of the almost prohibitive costs of material and equipment, it is doubtful if any new transportation medium of whatever nature could reasonably be expected to attain any marked development within the two and one-half years since the Barge canal has been opened. Our present rail transportation systems show little signs of material recovery from the staggering blows dealt them during the period named, although prior to the war they were justly presumed to be developed normally with the increased demands made upon them. To my mind, development of transportation on the canal has been set back fully three years, owing to the conditions through which we have passed and are now passing.

From the Superintendent of Public Works we hear further of this baneful influence and also learn what changes were taking place in the status of canal control. In his annual report, presented to the Legislature on January 15, 1920, Superintendent Walsh said:

"The task of restoring traffic to the waterways is a difficult one at best and nothing must be permitted to stand in the way of its progress. The first requisite in the undertaking is the formation of many strongly-financed, well-equipped carriers. I find there are men who look with favor on canal transportation projects and are eager to engage in the business under certain conditions, and one of the controlling conditions is that Federal utilization, control and jurisdiction of the waterways be discontinued. Few, if any, shipping men are willing to compete with a subsidized Federal canal service that operates without regard to cost and that assumes no obligation to produce a profit from its operations. The situation on the canals, therefore, if new companies are to be formed who will provide a service that will build up the tonnage, demands the termination of Federal control or utilization.

"I had believed that the termination of the Federal Control Act, returning the rail systems to their owners, would free the waterways from obstructing Federal influence. Transportation legislation pending in Congress, however, does not definitely establish the status of inland waterways on which the government had operated barges and it is proposed to transfer the government's inland waterway activities from the Railroad Administration to the United States Shipping Board, to be dealt with by the Shipping Board under the provisions of the 'Shipping Act, 1916.' If, in this manner, the government should continue its canal operations through the agency of the Shipping Board, the situation would be unchanged. There would still remain in operation a governmentally subsidized transportation service with which private enterprise is reluctant to compete, in fact, with which it declines to attempt to compete.

"I do not understand that the Shipping Board is authorized under the Shipping Act to operate vessels or barges it controls, but must permit of their purchase, lease or charter when persons or corporations came forward with a proposition that satisfied the terms and conditions purchase, lease or charter prescribed by the Shipping Board. If, therefore, pending legislation will be the means of terminating the Federal government's activities on the New York waterways and of releasing government barge equipment for private operation, the problem confronting the State is solved. On the other hand, if the measure now before Congress does not have such effect, I urge upon your honorable body the imperative necessity of the introduction in Congress and early passage of legislation that will rid the waterways of the State of the destructive governmental operation."

In 1919, however, Federal domination was somewhat lessened in degree. This was brought about largely through the efforts of Superintendent Walsh and we shall let him tell of it in his own words. In this same annual report he said:

"In view of the disastrous effect of Federal control of canal rates and equipment, as practiced by the Federal government during the 1918 season of navigation, determination was reached early in the year to limit and modify the extent of Federal jurisdiction.

"Several conferences were held with officials of the United States Railroad Administration and agreement reached as to the scope of the Federal government's activities during the 1919 season of navigation. First, the Railroad Administration agreed to waive its option of recharter on the 100 or more individually owned barges that it operated during 1918. By this agreement the independent barges were released for operation by their owners. Second, the government agreed that it would not control or attempt to control, either directly or indirectly, the operations of such independent canal carriers as might be established nor the local rates such carriers might publish. Third, the government agreed to operate the barges it had built in a through Buffalo-New York service exclusively and would not enter into competition with independent operators in the intermediate territory. Fourth, the Railroad Administration officials agreed that they would not attempt to influence the movements of the grain traffic from Buffalo and that independent operators might compete for such traffic on equal terms with the government barges. Fifth, the government agreed to establish a line of rates applying from New England and New York via canal to western territory and would restore a service on the Great Lakes to Lake Michigan ports. Sixth, the government consented to establish canal and rail rates through all practical points of interchange if and when traffic was created making such rates necessary."

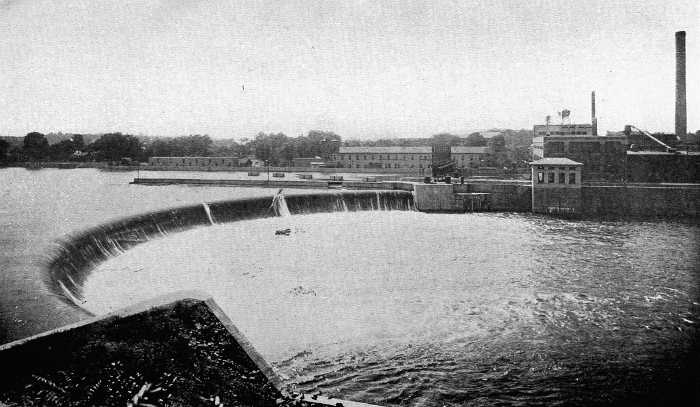

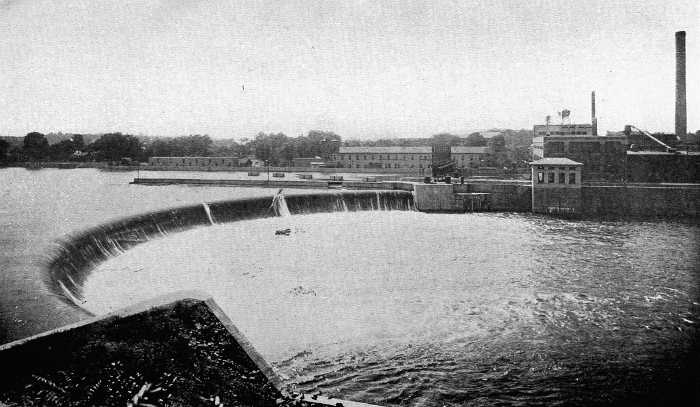

Fixed dam in the Oswego river, at Minetto. Nearly all of the Oswego canal is a river line, both old and new dams being used to effect this canalization. View shows a new curved dam of gravity type, built on the eastern side of the river, a lock in the center and power-plant head-gates on the western side.

Early in 1920 the railroads of the country were returned by act of Congress to their former private owners. It had been supposed that Federal jurisdiction over the New York canals also would cease whenever the railroad systems were given back. They had been taken under the authority of the same act as the railroads, known as the Federal Control Act, and moreover it had been the understanding of New York State officials that Government tenure was merely for the period of the war. When the bill to restore the railroads was pending in Congress it was said that some provision would be incorporated which would have to do with the policy of the Government toward inland waterways. Accordingly those in charge of canal affairs in New York were at considerable pains to caution the representatives of the State in Congress against permitting anything to be embodied in the bill which would continue Federal activities on the New York canals. Also inquiry of the conference committees of both Houses having the bill in hand brought the response that there was no provision that in any way affected adversely the New York canals. Shortly before the passage of the bill, however, it was learned in New York state that this assurance was in error. The bill as proposed by the conference committee provided that all barges on inland and coastwise waterways acquired by the United States in pursuance of the Federal Control Act were to be transferred to the Secretary of War and operated by him, so as to continue the lines of inland water transportation established during Federal control. The meaning of this provision was clear. Under it Government operations on the New York waterways would be continued. The New York members of Congress were immediately urged to have the bill amended so as specifically to exclude New York canals from its provisions. The sponsors of the bill, the chairman of the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce and the chairman of the Senate Interstate Commerce Committee, both declared that prior to the drafting of this section of the bill they had been informed that the Government had not taken over any transportation facilities on the New York canals nor was it engaged in operating any boats on them. Moreover, they were opposed personally to such operation if it was not desired by the people of the state.

The explanation of this occurrence we can only guess at. Superintendent Walsh's interpretation, however, is illuminating. He says, "The inclusion of section 201 in the Railroad bill in the form in which it was submitted to Congress unquestionably resulted from a deliberate misstatement of facts of the person or persons with whom the Conference Committee consulted. It is inconceivable that the information given the Congressional Committee was founded on ignorance and if so such ignorance of the activities of the Government by Government officials is appalling. It is my personal belief whoever imparted the information to the Conference Committee as to the inland waterway activities of the Government wilfully concealed the truth as far as the New York State Canal situation was concerned."

Because of the importance to the whole country of the chief features of the bill, it could not be delayed to revise one relatively small item, however much that was desired by those directly interested. Accordingly, the bill was passed, but shortly thereafter Senator Wadsworth introduced a resolution to exempt the Barge canal from its provisions.

On March 17, 1920, the State Canal Board adopted a strong resolution disapproving the continuation of Government operation of barges on the New York canals and declaring that in justice and fairness to the State all canal equipment used or acquired by the United States for Barge canal operation should be transferred in ownership to the State as a partial return to the State for furnishing, solely at its own expense, a waterway connecting the Great Lakes with the seaboard and placing it at the disposal of the Nation, and particularly in part compensation for what had resulted from the Government's canal operations in 1918 and 1919.

Immediately following this action the State Legislature passed a concurrent resolution of the same tenor as that of the Canal Board but going farther and actually requesting the transfer of the fleets to State ownership. Copies of this resolution were sent to the United States authorities.

A hearing on Senator Wadsworth's resolution was called by the Senate Committee on Interstate Commerce, at which New York canal representatives appeared and argued that Government operation was inimical to the successful development of commerce on the State waterways and prejudicial to the best interests of the people of the state. The resolution was favorably considered by this committee and was passed by the Senate.

At the hearing before the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce the State commercial interests were again represented in force and once more they protested against a continuance of Government operation on the New York canals. The Secretary of War, on the other hand, vigorously opposed the resolution, and representatives of his department painted a wonderful picture of what splendid results would attend the continued operation of Government barges on the State canals under the direction of the War Department. And as a cap-sheaf for New York's humiliation, in the light of her former magnanimity, representatives of the South appeared before the committee and insisted that if the Government were to cease its activities on the New York canals then the boats it had constructed or was constructing for that service should be transferred to the Mississippi and Warrior rivers.

We shall let Superintendent Walsh tell how this action ended and also what happened on the canals during the ensuing season. In his report for 1920 he said: "Congress adjourned before action was taken by the House of Representatives on Senate Joint Resolution 161 and the Federal government, under direction of the Secretary of War, through the Inland and Coastwise Waterways Service, administered by the chief of the Army Transport Service, has operated a fleet of 95 barges on the waterways of the State during the navigation season of 1920. The equipment operated by the Federal Government is supposed to be the last word in inland waterway barge design. The power units employed cost nearly $100,000 each. Twenty steel steamers, twin screwed, having 400 I.H.P each and cargo capacity of 350 tons were in service. Fifty-one steel barges, 150 feet long, 20 feet wide, 12 feet deep, with a cargo capacity of 630 tons each; twenty-one concrete barges, 150 feet long, 21 feet wide, 12 feet deep, with a cargo capacity of 520 tons each, and three wooden barges of the same general dimensions were operated. The total cost of the fleet was approximately $4,500,000."

We desire to add another quotation from Superintendent Walsh. He gives in this same report a brief résumé of Federal control on the New York canals in 1918, 1919 and 1920, the three years during which that control was in force. It is as scathing and as fearless an arraignment of Government operation as the most rabid and the most sorely disappointed canal enthusiast could desire. It reads as follows:

"The Report of the Director of Inland Waterways of the United States Railroad Administration for the year 1918 excuses the failure of government operations on the ground that the equipment to be had was obsolete and inadequate and the time permitted for the mobilization of a fleet and perfection of an operating organization was too short to permit of efficient results.

"The report of the Government for the fiscal year 1919 shows a loss of $506,807.38. The failure of operation is admitted but excused on the ground that the modern power units contracted for had not been delivered and such tow boats as were available for the movement of the new steel and concrete barges that had been delivered were inadequate.

"The report of the Chief of Inland and Coastwise Waterway Service for the fiscal year 1920, comprising only 45 days of the navigation season of 1920, shows a loss of $62,670.14. The deficit for the entire season of navigation will unquestionably exceed $500,000. Throughout 1920 the government had in full service its full complement of floating equipment, the most modern and most costly of any on the State waterways. The season's cargo capacity of the fleet if operated with reasonable efficiency would have been approximately 600,000 tons. The alleged causes for the failure of operations in 1918 and 1919 did not exist in 1920 yet the results were relatively far more disastrous. The government barges carried 197,017 tons during the season of 1920. In my 1919 report I showed that while canal commerce increased 7 per cent in 1918 that proportion carried by the government line decreased 2 per cent. During 1920 the government barges carried slightly less than 14 per cent of the season's total tonnage, their proportion decreasing another 2 per cent despite the fact that the very best equipment to be had was operated by the government and traffic was available in large volume, increasing about 15 per cent in total. A comparison of barge activity of the government fleet with barges operated by others shows that the type of equipment characterized by the government in 1918 as 'obsolete and inadequate' worked with much greater efficiency. The War Department fleet engaged almost exclusively in the through Buffalo-New York traffic, the long haul trade, yet the average miles per day made by government barges was but 24.4 miles as against the 25.7 miles per day made by independent boats. The average time per trip by government boat was 14.1 days, as against 7.9 made by the independent boats. One independent carrier having in service power units and cargo barges of the old canal type with a season capacity of about 120,000 tons carried during the year over 90,000 tons or 75 per cent of its capacity. Government barges carried less than 30 per cent of their capacity. Shippers have reported to the Department that government barges were as long as 75 days in transit from New York to Buffalo. Government barges with cargo valued at hundreds of thousands of dollars on which the shipper was paying interest charges laid at the Barge canal terminal in the city of Albany for several weeks. A time was reached when shippers of flaxseed from New York dissatisfied with the abominable service of the War Department line diverted their tonnage to the independent operators. Immediately the government decreased its rate on this commodity. The former rate was fair and reasonable. It is questionable whether the decreased rate was remunerative. The loss in earnings to one carrier resulting from the destructive competitive methods of the government would have been sufficient to pay a substantial dividend on the entire capital stock of the company.

"Not the least of the evils of government operations were in their effect on the commercial interests of the canal. The utter incompetency and rank carelessness of government employees manning the barges placed the canal structures in constant jeopardy. The movement of a government fleet was a serious menace to locks, dams and bridges. Navigating the waterway with complete disregard of rules and regulations the government boats wrought havoc with the channel buoy lights; badly damaged locks time and time again; were in collision frequently with other craft; were sunk here and there in the canal channel, and in one instance almost completely demolished a bridge. Reports continually reached the Department that officers and crews on government boats were intoxicated while on duty and incapable of safely performing their duties. A rehearsal of the accidents and damage caused by the incompetent and careless handling of government barges would entail more space than may be permitted in this report. Suffice it to say that had the conditions cited resulted from the operation of barges by a private company the privileges of the waterway would have been denied that company. As it was, the impression prevailed that since the War Department's Canal service was conducted through Act of Congress, the operation of the boats was outside the jurisdiction of the Superintendent of Public Works.

"Government operation on the New York canals in 1918 and 1919, under the Railroad Administration, was most deficient. Government operation under the War Department in 1920 was so replete with mismanagement, inefficiency and incompetency as to defy imagination. The fiasco of government operations in 1918, 1919 and 1920 demand that there be brought about an immediate termination of Federal operations on the New York State waterways. The people of New York have been compelled to assume a large share, nearly 30 per cent, of the million or more dollars lost by the Railroad Administration and the War Department in their ridiculous attempt to conduct a business enterprise. The commercial interests of the State demand that the government withdraw from business on the New York canals and cease competing with citizens of the State in a field where the government has no moral right to continue. To that end, I urge upon my successor and your Honorable Body the imperative necessity of early and forceful action that there may be introduced and passed in Congress legislation amendatory to the Railroad bill that will compel the immediate discontinuance of government operations on the Barge canal."

Federal control of the Barge canal was stopped in time to free the 1921 navigation season from boats operated by the Government. But Superintendent Cadle said in his report for the year that only through the most vigorous efforts of the Governor, the Legislature and State officials was this brought about. The Government boats were purchased and operated on the canal by a private transportation company.

1 Ninth Annual Report, N.Y. State Waterways Association, pp. 48-51.

2 Id., p. 41.

3 Tenth Annual Report, N.Y. State Waterways Association, p. 16.

4 Id., p. 45.

http://www.eriecanal.org/Texts/Whitford/1921/chap15.html