HISTORY OF THE BARGE CANAL

OF NEW YORK STATE

BY NOBLE E. WHITFORD

CHAPTER XII

OTHER DETAILS AND INCIDENTS

Pollution of Canal Waters -- Attempts to Secure Crescent Power -- Canal Lands for Municipal Parks -- Tree-Planting on Canal Lands -- Canal Lands for Industrial Use -- Proposed Wider Channel, Waterford to Oswego -- Bridge Dam Made Highway Bridge -- Old Canal Filled at Fulton -- War Time Military Protection -- Schenectady-Scotia Bridge -- Rexford-Aqueduct Bridge -- Bridges at Phoenix, Fulton and Minetto -- Elements of Efficient Canal Management -- Zones of Canal Influence -- Canal Visitors.

During the years of constructing the Barge canal there has been a multitude of interesting incidents which have been neither matters of policy nor yet affairs very intimately connected with the actual building but which have been more or less closely associated with the canal and are important enough to deserve a few brief words of notice. Of the many incidents only a few can new be reviewed. Of necessity these have but little connection one with another.

The first in order of time of those to be considered is the attempt to rid canal waters of pollution. In his report of 1907 Superintendent of Public Works Stevens discussed this subject at some length. What he said pertained largely to the old canal but a glance at his statements enables us to know what harmful practices had prevailed on the old waterway -- practices which in some measure were being carried over to the new canal. For years the citizens of the cities and villages through which the canal passed had come to look upon the waterway as the legitimate place for emptying sewers or receiving whatever noisome or waste materials they desired to be rid of. As a result, during the summer the waters were foul and in winter, when the canal was empty, it resembled a public dumping ground and an open sewer. The State could not well maintain a force for policing the whole length of the canals, and municipal authorities, both police and health officials, seemed to have fallen into the way of entirely overlooking violations of the penal code if the offenses were against the canal. The waterways accordingly had become displeasing to the senses and a menace to health. Inherently the canals were capable of being attractive. Some of the purest water in the state, from mountain streams or woodland brooks, was used to feed them. The disrespect thus engendered for the physical appearance of the canal could but be reflected in a feeling that the waterway was of little real use. How wide-spread was this opinion we have already seen, and the communities which were the chief beneficiaries from canal traffic were largely responsible for this conception, since they by their failure to enforce the law had fostered the evil practices. Mr. Stevens had instituted a reform and was trying to instill a wholesome respect for the canals by making them less offensive to sight and less detrimental to health.

Since the Barge canal lies largely in natural streams the conditions attending the pollution of its waters differ from those of the old canal. The tendency to use it as a dumping ground is not so great but the practice of making it a receptacle for sewers and industrial wastes still goes on. The desire to exclude pollution from our canals has now been reinforced by the incentive to keep clean our principal natural streams. Moreover the old custom of draining all sewage, without chemical or other treatment, into streams is gradually giving away to the modern idea of scientific disposal plants. But this change, if left to municipalities alone, is slow and so we find State officials endeavoring to hasten the time when our streams will be purified.

In each of his four annual reports State Engineer Bensel recommended legislative action to provide remedies for existing conditions. Early in his administration he had consulted with Governor Dix and the State Health Department on the subject of sewage disposal plants for municipalities along the canals. The existing statutes were inadequate to correct improper conditions. Prior to 1903 the State Department of Health had no power whatever to enjoin or remove sewage pollution from any State waters. In 1903 an act was passed which provided a remedy against future pollution but which, unfortunately for the cause of stream purification, specifically exempted municipalities and industrial plants that were discharging sewage and waste into State waters at the time of the enactment. An act of 1910 invested the Health Department with further powers but failed in effective purpose because under its limitations it was necessary, after full investigation and report, to establish the fact that the pollution was a public nuisance or a menace to health. Mr. Bensel's recommendations were unavailing. A change so radical would involve large expense for the municipalities and accordingly opposition was too strong to permit the passage of measures adequate completely to eradicate the stream pollution evil.

An incident of late 1909 and early 1910 is interesting, especially in the light of the recently-adopted State policy for the development of Barge canal water-powers. In November, 1909, the Cohoes Company, the power company which since 1826 has developed power from Mohawk river waters in the vicinity of Cohoes falls, petitioned the Canal Board, requesting the conveyance of certain lands, then a part of the old Erie canal, without compensation to the State therefor, and also the use of certain waters impounded by the new Crescent dam, as partial compensation to the company for damages alleged to have been caused by the construction of the Barge canal. Also a bill was introduced in the 1910 Legislature to authorize this company to use the waters impounded by Crescent dam.

The State canal officials were bitterly opposed to the proposed legislation. They considered it contrary to the broad policy the State, in their opinion, should adopt, namely, that of disposing of Barge canal water-powers under a general law, covering all cases, which should be to the benefit of all the people of the state rather than to a few individuals or corporations. Moreover, as was shown by the expert electrical engineer of the State Engineer's department, the company proposed to pay to the State annually from $3,000 to $7,500 for power which he estimated it could sell at a net profit of $65,000. The opposition of the officials prevented the passage of the bill. One thing State Engineer Williams did to bring about this result was to print the documents pertaining to the affair in the Barge Canal Bulletin and send this publication broadcast over the state.

We should notice also a few recommendations the State Engineer made from time to time for employing Barge canal lands for useful public or industrial purposes. In 1909 State Engineer Williams suggested the advisability of using certain elevated areas that had been created by depositing material from Barge canal excavation. Where these areas were near cities and villages they could be converted into municipal parks and such use would greatly benefit the people of the localities and would not be detrimental to the canal.

Another suggestion Mr. Williams made was to plant trees on spoil-banks that were unsuited to cultivation. When he first recommended this, in 1910, he had in mind particularly the sandy stretch to the east of Oneida lake, where such trees, in addition to utilizing waste lands and lending beauty to the landscape, would serve the very useful purpose of stabilizing the shifting sands. In suggesting this action later, in 1918, Mr. Williams advised the use of a much wider range of canal lands for tree-planting. A few pieces of land covered with material deposited from excavation had been reconveyed to former owners, but in the majority of cases it seemed wise for the State to retain possession, since the areas might be needed again, if in the course of maintenance more material should be taken from the channel. Moreover these lands were often in small parcels of irregular shape and covered as they were with three or four feet of newly-excavated material were of little value to private owners, especially for agricultural use. Originally many of these areas were rich bottom-lands that would be excellent for trees, once their roots had struck through the new material.

Another and a very important prospective use for canal lands was that of serving as sites for industrial plants. This suggestion came from State Engineer Bensel. In the course of construction low and waste areas had been filled and also arable lands had been made non-productive, and all together there were available numerous desirable sites for manufacturing and business plants. These were situated near the canal of course, where they would be in direct touch with water transportation, and generally rail connections also could be easily provided. And besides these advantages, factories on such sites, as State Engineer Williams pointed out in his subsequent advocacy of this project, would be in position to avail themselves of canal water-power, when such power should be developed. These suggestions have been followed in some measure. For example three large oil companies have located near the Syracuse terminal.

State Engineer Bensel made a recommendation to widen certain portions of the canal, which however was never carried into effect. He judged that a part of the traffic from the Welland canal would desire to utilize the Barge canal between Oswego and New York city, thus reaching the Atlantic coast by a shorter route than that through the St. Lawrence river. Barge canal locks would accommodate the boats which navigated the Welland canal, but there were approximately fifty miles of canal between Oswego and Waterford which had a bottom width of only 75 feet, not enough to allow two boats of maximum lock capacity to pass one another. Mr. Bensel called the attention of the Legislature of 1913 to this condition and recommended that it consider the question of making an additional appropriation for the purpose of increasing these narrow portions of canal to a bottom width of 110 feet. The estimated cost of such widening was $2,000,000.

The movable dams of bridge type have already been mentioned several times. Although the bridges were built primarily to function only as parts of the dams, they were inherently capable of serving also as highway bridges. There are eight of these movable dams in the lower Mohawk and some of them are situated where highway bridges across the river would be most acceptable to the inhabitants. At one dam, that at Rotterdam, the bridge has been converted into a highway structure. This work was done under an act (chapter 714, Laws of 1913) for the specific purpose, a special appropriation being made. In this instance the State bore the expense. Whether the State or the municipalities benefited or both together will pay for changes to others of these bridges, if they should be converted into highway structures, is a question still to be settled.

A work of considerable importance to Fulton, on the Oswego canal, was that of filling the channel of the abandoned canal within the city. This work was done under special authority of chapter 530 of the laws of 1914, which however directed that the money for it should be taken from the Barge canal fund.

A feature of our war-time experience was the stationing of military guards at all strategic points on the Barge canal -- places where by using explosives the waterway could be so damaged as to cause long interruptions in navigation as well as large financial loss. At all of the locks, dams and other important structures these details of soldiers were encamped. Visitors were not permitted at these structures and only persons who had passes duly signed by the proper officials and who had actual business to transact were allowed upon them. The canal officials took pains to make the soldiers as comfortable as possible during their rather long stay, especially at the outlying posts.

There are a few bridges over the Barge canal which for one reason or another can be regarded as only partially belonging to the canal enterprise. The largest and most elaborate of all bridges spanning the new waterway -- the one which joins Schenectady to Scotia -- is of this class. Before the State got around to rebuilding the near-by old bridge the residents of Schenectady conceived the idea of putting the new structure a half mile farther west, so that the approach to the city would better suit their plans, and substituting for the somewhat modest but, to the minds of canal officials, entirely adequate bridge an imposing structure made up of numerous concrete arches. When the subject was broached to State Engineer Williams he strongly opposed the plan. The cost would be many times that of a bridge sufficient to meet all canal needs. But the people of Schenectady and vicinity began to agitate the project. They advertised the structure as an essential part of the main east and west highway across the state, christening it the Great Western Gateway. They enlisted the support of the whole Mohawk valley and even the region beyond, and came down to Albany in such force that the Legislature was constrained to grant their request. First the State Engineer was directed to make plans and estimates. This was in 1917. Then in 1919 construction was authorized in accordance with these plans. The bridge is of concrete arch construction, having twenty-three arches. These range in span from 106 to 212 feet. The whole structure, including approaches, is about three-quarters of a mile long. The money for construction comes from three sources -- special legislative appropriations, funds supplied by the city and county of Schenectady and the village of Scotia and a sum set aside from Barge canal moneys. The bridge is now nearing completion.

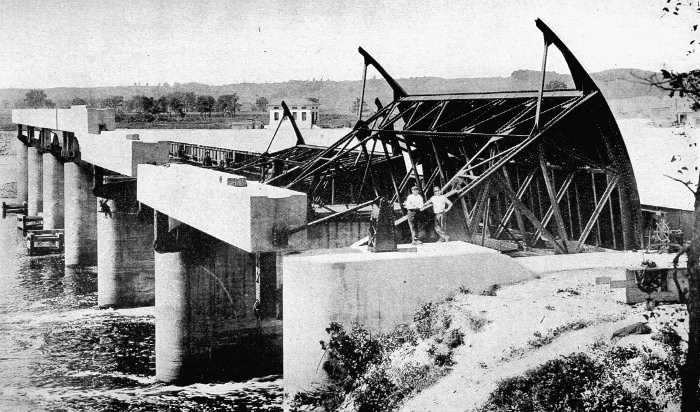

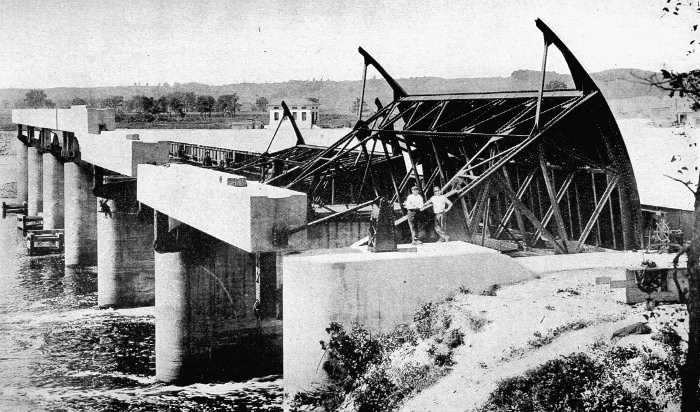

Another bridge, built because of Barge canal construction but not a part of it, is the one across the Mohawk river joining the village of Rexford and the hamlet of Aqueduct. Here the old canal used to cross the river on what was known as the Rexford Flats aqueduct. The new structure utilizes parts of the old aqueduct, but a steel span crosses the new canal channel. Chapter 176 of the laws of 1921 authorized the work and provided the funds.

Three long bridges over the Oswego river, built during the course of canal construction, were paid for only in part by the State. These bridges, at Phoenix, Fulton and Minetto, are all concrete arch structures. The State in each instance bore the expense of only the span across the canal, the remainder having been paid for by the towns connected by each bridge. At Fulton the canal span is an arch, like the rest of the bridge, but at Phoenix and Minetto the State spans are, respectively, a bascule and a convertible, the latter being capable of conversion into a bascule.

In the 1920 annual report of Superintendent of Public Works Walsh, presented to the Legislature just as he was retiring from office, we find a discussion worth noticing. He was giving his views with reference to the necessary elements of efficient canal management. In considering what he had to say it must be remembered that as a practical canal transportation operator of many years standing he had become keenly aware of certain defects in the management of the State waterways and then as head of the department he had viewed the subject from a new angle and had learned the difficulties in the way of securing better operation.

Mr. Walsh began his discussion by commending the progress made in the preceding double decade. Prior to that time it had been the generally accepted doctrine that the canal system was a legitimate field for political manipulation, and as a result nearly the whole roster of employees had been changed with each change of administration. But even before the new canal had come into use a better condition had begun, and later, when the elaborate machinery of the new type of structure demanded skilled operators, a large part of the working force was selected by competitive civil service examinations and men of a much higher grade were obtained. Such action had met with general approbation and it was for the continuation and extension of this practice that Mr. Walsh was asking -- the putting of canal operation and management on a business basis, entirely divorced from the domain of politics. Party lines had been obliterated in the agitation of canal improvement, said Mr. Walsh, and now that the new waterway had become an essential factor in commerce, strict business principles should be applied to its administration, some degree of permanency should be assured in the service and every employee should be made to feel that his term of employment depended solely on his attention to duty and his fitness for the work. But it might be, in Mr. Walsh's opinion, that the root of the trouble lay in the impermanency of the position of Superintendent, which in its legal status was no more definite that that of a humble bridge tender. His tenure of office was solely at the Governor's pleasure. The provisions governing the office harked back to the time when the canals were regarded as the battlefield of politics, when campaigns were won and lost on the success or failure of the canal administration. But those days had passed. The State's waterways were, gradually, demanding the eradication of all elements except those tending to commercial success.

Taintor gate section of a dam in the Hudson river, near southern end of the Champlain canal. Each of the six gates has a clear width of 50 feet. Top of gate, when lowered, is 17 feet above the sill. Remainder of dam is a fixed structure, At its farther end is located a lock.

Aside from the all-important matter of transportation, other vast interests were intrusted to the Superintendent of Public Works; millions of the State's moneys were dispensed by him annually; questions of enormous importance were presented to him for decision almost daily. The efficient conduct of the affairs of the department demanded the services of a broad-minded executive of wide experience and also a continuance in office for a specific term of reasonable duration. Since gubernatorial elections take place biennially, the Superintendent's term might be limited to two years. This had often happened and occasionally the time had been less than two years. Whenever a change should occur in the office of chief executive of the State, whether in the same political party or another or even, it might be, in the midst of a term, the Superintendent must be prepared to vacate his place in favor of the Governor's new appointee. If a Superintendent's services were limited to two years, only a small portion of that time could be devoted to the execution of policies which in his judgment seemed best for the State. More than half of the first year would have elapsed before he could acquaint himself with the vast property under his charge, the important interests he must guard and the facts as to the actual working out of the policies of his predecessor. After his own plans had been formulated, the effecting of any important changes must of necessity be gradual and slow and the result was that the navigation season of the second year would be well under way before the newly-adopted policies should be even in operation.

This situation, to Mr. Walsh's mind, was impossible. His remedy was the fixing of a definite term of office, at least five years, with the incumbent, like other State officers, subject to removal before the end of his term only upon stated charges and after a public hearing. Moreover, as far as possible the office should be removed from politics. To accomplish this latter result Mr. Walsh recommended an innovation in State affairs -- nothing less than legislation which in effect would vest the nomination for Superintendent of Public Works in the recognized business agencies of the state. While this principle as a State policy might be considered as without precedent, really it had already been applied, not only in the case of the canal itself but in other State matters as well.

During the course of canal construction one particular study was made which deserves brief notice. It is a study which throws much light on the potential influence of the canal on the transportation problems of the whole state. The object of the study was to learn what proportions of the state's population were in either close or remote touch with the canal. The various branches of the canal system penetrate to many parts of the state and in the study under discussion this system was considered as consisting of all the State waterways of Barge canal dimensions. Although Lakes Erie and Ontario and the St. Lawrence river might with propriety have been regarded as parts of the waterway system, they were not so considered in this particular study. If these bodies of water had been included, the showing in favor of the canal would of course have been still better. From the study it appears that 73 1/2 per cent of the population of the whole state is within two miles of the waterway system. In like manner it is seen that 77 per cent population is within five miles, 82 per cent within ten miles and 87 per cent within twenty miles. Looking at the facts from a different angle it appears that 46 per cent of the total area of the state is within the twenty-mile limit. Considering two other distances from the waterways, fifty and seventy miles, the possibilities of a combined canal and automobile traffic become apparent. These are the respective distances which motor trucks of 3 1/2 and 2 tons capacity can cover in a day's run, going and returning. The territory within fifty miles is 71 per cent of the area of the whole state, while that within seventy miles is 88 per cent of this total area. A productive field for motor truck operation in connection with the enlarged canals is thus revealed. Since New York's population is approximately one-tenth that of the whole country, we see that about seven per cent of the people of the United States are within a half hour's walk of the New York waterway system. Translated into numbers this percentage represents about seven million individuals. It is apparent then what it means to the State and also to the country at large that the products of these seven million people and the supplies they need may have available the means of cheap water transportation, especially after the traffic shall have been developed to the full extent of which the new canals are capable.

Another interesting feature connected with the Barge canal is the visitors it has attracted. The new waterway has been the Mecca of many pilgrimages. Of course it is not possible, even if it were desirable, to enumerate all of these, since no record has been kept of the great majority of them, but a few notable examples may be mentioned. Probably the largest single company to visit the canal was composed of delegates to the International Navigation Congress. This Congress convened in Philadelphia, Pa., in May, 1912. Delegates from all over the world were in attendance, some forty countries being represented. After the convention many of the visitors joined in an excursion which had as one of its principal objectives the inspection of the Barge canal throughout its entire length across the state. This party traveled by special train and was large enough to require twelve cars for its accommodation. Two days, June 7 and 8, were spent in the trip from Albany to Buffalo, several rather long stops being made on the way to allow close inspection of canal structures. Thus the party had a chance to walk over the land line at Waterford, to visit the movable dam at Fort Plain and the lock of 40 1/2 feet lift at Little Falls, to go over the interesting work of canal construction and railroad relocation at Rome or to take automobile and visit the Delta dam, and to get a close view of the tandem locks and other structures at Lockport. Other parts of the canal, of course, could be seen from the car windows throughout most of the trip. Dr. Elmer L. Corthell, member of the Advisory Board of Consulting Engineers during the early stages of Barge canal construction, was much interested in the affairs of the Navigation Congress and he was largely responsible for arranging the excursion over the canal. Many of the delegates were engineers and were especially interested in so remarkable an engineering project as the new canal. Four or five engineers from the State Engineer's department accompanied the party.

Later in the same year another party, composed largely of foreigners and traveling by special train, visited the Barge canal, but in this case the inspection of the canal was but one of several interests. The trip made by this company was known as "The Transcontinental Excursion of 1912 of the American Geographical Society of New York," and was in celebration of the sixtieth anniversary of the Society and of the completion and occupancy of its new building, situated at Broadway and 156th street. The excursion started from New York on August 22 and after traversing the continent on a northern route returned by a southern route and reached New York on October 17, disbanding after a closing dinner at the Waldorf the next evening. Some of Europe's most distinguished scientists and scholars were in the company and everywhere along the route they were welcomed by citizens and organizations and heralded by the press in such manner as became their high standing. The party consisted of forty-three foreign members, from thirteen countries of Europe, and about a dozen permanent American members, but the director of the excursion, Professor William M. Davis of Harvard University, had arranged for many temporary members to be with the party for one, two or three days at a time in regions where they could serve as guides and helpers by reason of their own studies or their familiarity with certain local conditions. Increased by these temporary members the American contingent numbered ninety. Among the temporary members was a representative from the State Engineer's department, who was with the party from Albany to Buffalo on August 22 to 24 and also at the closing dinner at New York. At the request of the director of the excursion this representative was designated by the State Engineer and it was his task to impart to the visitors information concerning the Barge canal. It fell to the lot of the writer to be this canal representative and he observed that the members of the party, especially the foreign members, showed much interest in the new waterway, more in fact than was manifested by the engineers who earlier in the year had visited the canal with the excursion of the Navigation Congress.

In the summer of 1913 an inspection of the canal was made under the auspices of the Buffalo Chamber of Commerce. This trip extended from Buffalo to Albany and consumed three days. It was conducted personally by State Engineer Bensel and his Deputy and Division Engineers, he having attended to making arrangements for the excursion after the men from Buffalo had expressed a desire to take such a trip. The Buffalo Chamber of Commerce was the first commercial organization in the state to undertake anything of this kind. Its purpose was to afford its members opportunity to acquire first-hand information in regard to the canal and the progress of its building. The utter lack of knowledge concerning the canal on the part of the chambers of commerce, boards of trade, cities, villages and the people in general throughout the entire state, and even a well-defined apathy in many places were appalling to those members of the Buffalo organization who had the welfare of the canal at heart. They determined, therefore, to make such a condition impossible in their own body and at the same time to set an example for other organizations.

The engineers who have visited the canal singly or in small groups are numerous. They have come from all parts of the world, often being sent by their governments to make a careful study of the whole waterway or some special type of construction. Some of these engineers have been about to design canals for other localities. Of this class was a company of men who had in charge of the Lake Erie and Ohio River canal, a project to join the Ohio river at Pittsburgh with Lake Erie. In this instance members of the Ohio and Pennsylvania commission, as well as the engineers, visited the Barge canal. So too the Federal engineers who were to design the prospective Lake Erie and Lake Michigan canal, joining the heads of Lakes Erie and Michigan, and certain of the intracoastal canals along the Atlantic shore, as well as other national projects, have been interested visitors to the New York waterway. These engineers have always been shown every possible courtesy and sometimes the State Engineer has assigned a member of his corps to accompany them on their trips.

The delegates to one of the annual meetings of the Atlantic Deeper Waterways Association, convening in New York city, were taken on excursion up the Hudson, in order that they might appreciate the importance of the Deeper Hudson project, and then the trip was continued to include the spectacular land line section of the Barge canal between the Hudson and Mohawk rivers in the vicinity of Waterford.

The visit of chief importance perhaps, as far as its influence is concerned, was that of the fall of 1921, when a company composed of about forty members of Congress, representing the western, southern and southwestern states, and manufacturers and business men of the Great Lakes territory, together with a goodly number of New Yorkers, were taken in boats up the Hudson and through the new canal under the auspices of certain chambers of commerce and public spirited men of the state. Inciting this excursion was a desire to combat what New Yorkers consider is the pernicious agitation for the St. Lawrence ship canal. The attempt appeared to be successful. The members acknowledged that their former ideas of the inadequacy of the Barge canal were entirely erroneous and expressed their determination to oppose the St. Lawrence scheme. Several members of the Public Works department accompanied this excursion.

http://www.eriecanal.org/Texts/Whitford/1921/chap12.html