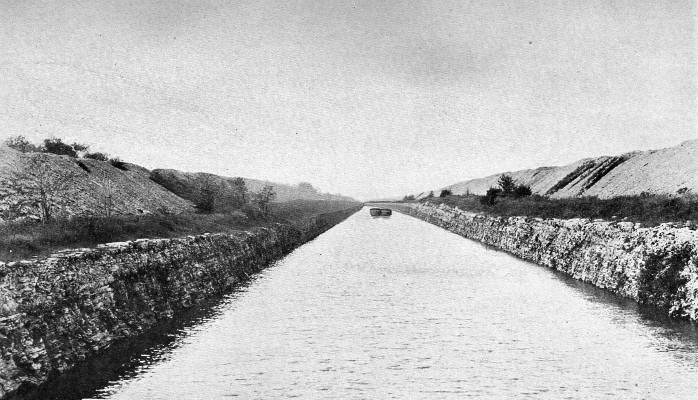

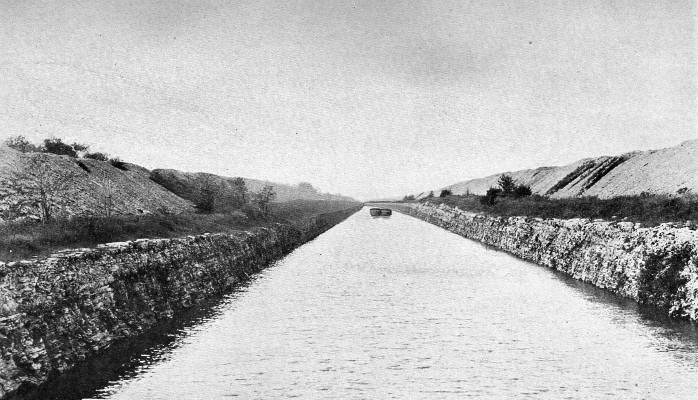

Channel in rock cut, near Rochester. The length of this rock cut is five miles. It reaches a maximum depth of 40 feet. The channel has a bottom width of 94 feet. In some places the sides were cut by channeling machines.

Accounts of the progress of construction work year by year and also of the new work being put under contract appear in chronological sequence in the chapter but are not listed in this outline. The other chief items are the following: First Contracts Awarded and Construction Begun -- Study of Rome Level Water-Supply -- Studies of Rome Routes -- Advisory Engineer for Superintendent -- Criticisms by Superintendent -- Barge Canal Bulletin Begun, 1908 -- Federal Aid for Termini and Hudson Canalization Asked -- Survey and Assumption of Hudson River by Government -- Cayuga and Seneca Branch and Terminals Added -- Leaks Occasioned by New Work -- Oswego Partly Closed, 1909 and 1910 -- Rival Projects in 1910 -- Mohawk River Contracts -- Tests of Models of Proposed Medina Arch -- First Locks and First New Sections Used, 1910 -- Canal Affairs Reviewed in 1910 at Request of Governor -- Statement Concerning Railroad Crossings -- Government Adoption of Hudson above Troy Questioned -- New Plans for Lock and Dam at Scotia -- Break in Bushnell's Basin in 1911 -- Terminals Begun -- Serious Break at Irondequoit Creek -- Publicity of 1912 -- Flood of 1913 -- Beginning of Navigation Aids -- Oswego Closed for Sixth Year -- Lyons Routes -- Court Decision on Railroad Crossings -- Exhaustion of Appropriation -- Attempted Legislative Investigation -- State Engineer's Reply -- Full Discussion of Exhaustion and Reasons for It -- New Referendum for Funds -- Referendum Explained -- Eastern Section of Erie Opened with Ceremony, 1915 -- Extended Review of Railroad Crossing Problem -- Other Sections Opened, 1916 -- Lake Navigation Aids Studied -- Possible Deficiency of Cayuga and Seneca Fund Reported -- Rochester Work Begun -- Its General Plan -- Former Land Acquisitions Delaying N.Y. City Terminals -- Canal Open, Ocean to Lake Ontario, 1917 -- First Warehouse and Machinery Contracts Let -- Intense Activity in 1917 -- Tonawanda Situation -- Rome Centennial Celebration -- Cayuga and Seneca Fund Increased -- Whole Canal Open, 1918 -- More Terminal Funds Needed -- Pier 6 Opened with Ceremony, 1919 -- Terminal Fund Increased and Elevators Added -- New System of Buoy Patrol -- Statements of Terminal Work Accomplished -- Elevators Begun -- Governor Miller's Interest in Canal.

In our study of the Barge canal we have not as yet said much about the actual work of construction, but rather have been considering chiefly questions of policy and matters of procedure. Reverting now to the beginning of the year 1905 we recall that, because certain contractors, upon request, had submitted both lump sum and itemized proposals on the first contracts and the legality of this action was in question, Superintendent of Public Works Boyd had refrained from awarding these contracts and had left the disposal of the whole subject to his successor. Early in January the new Superintendent, N.V.V. Franchot, asked Attorney-General Mayer to render an opinion on the question. This opinion held that the Barge canal law rather than the general canal law governed the methods of asking for proposals and awarding contracts and that the Barge canal statute invested the Superintendent with large discretion, and as the contractors had acted in conformity with the request in his advertisement for proposals the bidding was lawful; also that it was the duty of the Superintendent alone to determine which was the lowest bid and to act in accordance with his best judgment for the interests of the State. Of the six contracts for which tenders were asked at the first opening lump sum proposals were received on only three and in each case itemized bids were also received which on their face were lower than the lump sum bids. The Superintendent, therefore, awarded the six contracts, each to the contractor whose bid was lowest on that particular contract. The experiment of asking for lump sum proposals ended with this first letting. Thereafter throughout the whole course of construction itemized bids have prevailed to the exclusion of any other method.

By April and early May, 1905, all of these six contracts had been signed and soon afterward the work of construction was begun. The first actual contract work was performed at Fort Miller, on the Champlain canal, on April 24, 1905; the first work on the Erie canal was done at Waterford on June 1, 1905. During the early months of these first contracts there was no remarkable showing in the amount of construction work accomplished. The contracts were all large, some of them quite large, and time was needed to assemble the various plants, most of the dredges, scows, excavating apparatus and other large machines having to be built on the sites of the work.

While it seemed at the time that good progress was being made during the early years of construction, in the light of later accomplishment such progress appears very slow. But this was only what naturally might be expected. In large undertakings of this character, for which carefully-wrought plans and extended preparations have to be made, it usually takes several years to get the work well under way. For a while after that it goes with a rush and later, as the end approaches and less and less remains to be done, there is a gradual slowing down. Precisely the same law seems to hold as applies to moving bodies. At first force is required to overcome the inertia and then the momentum carried the body until another force stops it, and the larger the body the greater the force needed to start it and also the greater the momentum that keeps it going.

In the first two years of the work 1905 and 1906, the apparent result was very small, less than a million dollars being paid for construction. The next two years showed a large increase and the two after that an increase still larger by many times. But these were all years of planning on the part of the State and of preparation as well as accomplishment on the part of the contractors. Indeed the State Engineer was severely criticised for not completing all plans for all parts of the enterprise before any construction whatsoever was begun. But probably he would have been more severely criticised for doing other that he did.

After these six years there came four peak years in construction. During these four years more than fifty million dollars worth of work was done, but besides the momentum acquired from previous years there were two new additions to the project -- the Cayuga and Seneca canal and the terminals -- to augment the total of accomplishment for the period. No year since these four has witnessed so large an amount of work being done, but as long as there remained structures or canal to build each year's record was large and the aggregate has been very large.

In the present account of constructing canal and terminals it cannot be hoped to go into details very minutely. Nor indeed does such a course seem necessary. These details are available, however, for him who must have them. Enough of the records have been published in State documents to furnish all the information the ordinary investigator desires. The annual reports of both the State Engineer and the Superintendent of Public Works have told year by year what progress was being made and what portions of the canal had been built. The account in the State Engineer's report has taken up each contract quite at length and told in detail just what had been done and what it had cost. The Barge Canal Bulletin was issued monthly during most of the period of construction and its record went into still more circumstantial detail. It published month by month the progress made in preparing plans, also the facts in regard to the approval of plans, advertising for bids, the itemized bids received and the award of contracts, and then it described the work done each month on each contract till all was finished or the contract was terminated for some cause. The Bulletin account included also a record of the money value of all work planned, contracted for and done. The Comptroller told in an annual report of the money being spent on the project. The two boards which have had to do with the Barge canal -- the Canal Board and the Advisory Board of Consulting Engineers -- each published the minutes of its several meetings and at the end of each year these were bound in an annual volume. Also other State officials have had a part in Barge canal construction and their reports add to the sum of available information. Other records, even to the most minute detail, preserved mainly in the archives of the State Engineer's office, may upon occasion be consulted by those who must carry their search beyond these published accounts. With all of this wealth of information so easily accessible it seems best to devote the text of the present volume to a consideration of subjects of a somewhat general import and to limit the details of specific work performed to an appended table of contracts.

The most important events in canal history for the first three or four years of the period of construction have already been discussed in the chapter on early policies and methods. The actual work of building the canal was proceeding, not so rapidly as in subsequent years, but still proceeding, and while there were as many perplexing problems of construction for the engineers to solve as is the usual lot in large undertakings, they were not of sufficient moment to leave any lasting impress on the records.

Perhaps the most important of the things not already mentioned was a thorough investigation of the water-supply available for the Rome summit level of the new canal. This study was made in 1905 under State Engineer Van Alstyne by William B. Landreth, Resident Engineer, and it was reviewed by Emil Kuichling, the consulting engineer who had been employed to make the water-supply investigations during the preliminary survey of 1900. This study had a most important bearing on some of the plans which were about to be made, but it need not now concern us except to call our attention to the fact that such studies, of a purely technical character, were constantly being carried on in the work of designing the numberless structures and portions of the channel throughout all the years of canal construction. In the days of the original canal, engineering was a new and not a very precise science and rule-of-thumb methods largely prevailed. The early engineers used good judgment, however, and were spared grievous failures. But now engineering has so advanced that calculations are made for sizes, weight and strength down to the last minute detail and whatever may influence the stability as well as the usefulness of a completed structure is carefully considered in making the design. Engineering has become also a profession of many precedents and for successful designing there is needed a broad knowledge of what others have done in a like situation, or an originality which is so keen in foresight as not to make fatal mistakes.

In 1906 several important pieces of work were put under contract. Among them were the first of the movable dams of bridge type on the Mohawk river and the locks beside them, also the northern half of the Champlain canal, embracing the portion between the Hudson river channel at Fort Edward and Lake Champlain at Whitehall, the remainder of the land line section between the Hudson and Mohawk rivers at the eastern end of the Erie canal, a stretch near the western end of the Erie and another in the vicinity of Little Falls, and the portion of the Oswego canal extending through Fulton.

The record of contracts awarded in 1907 is not very large, although one having a length of nearly forty-four miles was included. This embraced the line in Oneida and Seneca rivers west from Oneida lake and extending to Mosquito Point. Besides this long stretch of channel there was a short section at the north end of the Oswego canal, which included the novel siphon lock at Oswego, and the fifteen miles at the lower end of Mohawk river canalization, containing the massive dams at Crescent and Vischer Ferry.

The beginning of the 1907 marked the coming of a new incumbent, Frederick Skene, to the office of State Engineer. There have been several such occasions in the history of the Barge canal and it will be noticed that whenever a break of this character has occurred in the continuity of the engineering organization it has been reflected in various ways, generally in a temporary slowing down in the work of preparing plans or carrying on construction. Whenever in Barge canal construction there has been a change of men in the State Engineer's office it has happened that it has been a change also in the political complexion of the incumbent.

Among the studies which occupied the engineers in 1907 there appear several of considerable importance. One had to do with the canal alignment at Rome. Plans had been well advanced on what was called the north route, which would carry the channel through the city, making necessary some objectionable bridge approaches and interfering with business interests to quite an extent. The citizens of Rome objected and plans were halted till a decision could be reached. Meanwhile investigations for a better line were being made. The solution of this problem was not easy. If the line were thrown farther south, then there involved on the one hand some very costly railroad crossings or on the other hand an entire change of railroad location for a long distance, this change including a new station for the city and being also very costly. Several years were spent on this problem before it was finally solved.

It is interesting to notice how the canal alignment has shifted back and forth in Rome and how at each change there has been difficulty in pleasing the inhabitants. Rome shared in the first artificial waterway improvement in the state. The Western Inland Lock Navigation Company, chartered in 1792, built as one of its undertakings a canal along the portage between the Mohawk river and Wood creek. This channel was near to the line just mentioned, that called the north route. When the State constructed the original Erie canal the location was changed to the south, much to the displeasure of the citizens. During the first enlargement of the Erie, that of deepening to seven feet, the canal came back north to the first location and again there was dissatisfaction. When it was proposed to build the Barge canal along the northern route the people wanted the line changed again. To anticipate the final decision it may be said that the new waterway has now been built much farther south than even the original Erie canal.

Among the other studies of this year was one on the Rochester-Lockport level, of which mention was made in a former chapter; also one to determine a type of dam and an arrangement of spillways to lessen rather than aggravate flood conditions in the Genesee river at Rochester, and another to find a kind of dam for the Oswego river at Phoenix which would prevent flood damages in Onondaga lake and at Syracuse. There was a study too of the harbor problem at Syracuse and this proved a question about which there were such divergent ideas that several years passed before a final decision was reached.

In 1907 the Superintendent of Public Works in his annual report complained that the new construction was making it very difficult to keep the canals open during the navigation season. This was especially true with regard to the Oswego canal and in his report a year later he recommended that the Legislature make provision for closing this branch during the season of 1909. It will appear later how during six seasons, beginning with 1909, portions of this canal were closed.

In 1907 the Superintendent was permitted by legislative authority to appoint an advisory engineer in his department. While the Barge canal law provided for all engineering work to be done by the State Engineer, it laid certain duties on the Superintendent which in the judgment of Mr. Stevens, the incumbent at that time, required the assistance of one competent to advise concerning engineering matters. The engineer appointed was Joseph Ripley, a man who had had charge under the Federal government of construction on the Sault Ste. Marie canal and who had but recently held very important positions on the Panama canal, having been a member of the board of consulting engineers, having had charge of designing the locks, dams and regulating works, and having been assistant chief engineer. It will be seen that later Mr. Ripley held other important positions connected with the Barge canal.

A rather interesting discussion is found in the 1907 annual report of Superintendent Stevens. It is a criticism of the way the work of construction had been carried on by the State Engineer. The Superintendent based his contention on an interpretation of section six of the Barge canal law, holding that this section directed the State Engineer to make plans for the whole project before any contract whatever should be awarded. He argued that a policy after this order not only would carry out the intent of the law but also would have been of the make-haste-slowly variety, which would accomplish more in the end, and moreover that it would have been in better accord with good business principles. He complained of the slow progress being made and intimated that it was due to the adoption of this wrong policy. From this argument he passed easily to a reopening of the main issue in the whole State canal problem -- whether a ship canal would not be preferable to a barge canal -- and before he finished he recommended that the Legislature should memorialize Congress to join with New York in making that portion of the Barge canal which extends from the Hudson river to Lake Ontario, by way of the Mohawk river, Oneida lake and the Oswego river, a ship canal of the type contemplated in the report of the Deep Waterways Board of Engineers in 1900 and also that such pressure should be brought to bear on Congress as to accomplish the suggested plan.

It is somewhat difficult to follow the logic of Mr. Stevens' argument. Knowing how great an amount of designing work the engineers have found necessary throughout the larger part of the construction period, it does not readily appear that the time required for building the canal would have been shortened materially by delaying construction till all plans were ready. His thought evidently was that the purpose of the law as he interpreted it was to guard against building the canal in such a manner as to overrun the appropriation. We have seen already that the State Engineer, because of charges during the canal campaign that the estimates were unreliable, had perceived the necessity of ascertaining as accurately as possible the whole probable cost. By his selection of a wide variety of work for the first contracts, thus making them in effect test contracts, he had demonstrated with what appeared to be reasonable certainty that the entire canal could be finished within the appropriation. In a former chapter it was seen also with what care and thoroughness the State Engineer had proceeded during the first years of planning. His policy indeed had virtually been to make haste slowly. It may be said in passing the Mr. Stevens' interpretation of the law was deemed untenable by legal authority. The Superintendent's suggestion that the whole work should have been put into ten contracts and that this arrangement would have resulted in less contract machinery and at the same time would have hastened contract work seems rather absurd.

The whole argument shows a lack of an appreciative understanding of the engineering features of the project, but on the other hand, it must be remembered that Mr. Stevens was a remarkably astute and successful business man. It cannot be denied, however, that in the attitude of Mr. Stevens and also in that of others who have held the office of Superintendent during Barge canal construction there may have been a querulousness which seems to arise from resentment at the inactive position in which they found themselves under Barge canal law, in evident forgetfulness that it was due to the evils of dual responsibility under the nine-million project that they had thus been shorn of power.

Mr. Stevens' advocacy of the ship canal plan illustrates the persistence of this idea. Throughout the whole period of the Barge canal and in all parts of the state many persons have continually been met who would shrug their shoulders whenever the canal was mentioned and say that perhaps it is all right but it ought to have been made large enough for ocean-going ships to reach the Great Lakes and moreover the Federal government should have built it.

A year later Mr. Stevens again deprecated the lack of progress and suggested that power given under the Barge canal act should be invoked and the work taken from certain contractors and put into the hands of the Superintendent. Occasionally in the course of contracting the canal this drastic remedy has been resorted to, but such measures have been reserved for extreme cases of failure on the part of the contractor and then not until no other way seemed open.

In the years 1907 and 1908 we find the beginnings of several important canal affairs. Both the State Engineer and the Superintendent of Public Works were recommending canal terminals, but these suggestions were limited to New York and Buffalo and the terminal idea of broad scope did not appear until later.

In January, 1908, State Engineer Skene adopted a policy that was rather wide-reaching in its influence and which was continued by all of his successors. This was the issuing of a monthly publication, the Barge Canal Bulletin, which ran from February, 1908, to January, 1919. Since this publication is discussed at some length in the chapter on advertising the canal, it need not at present have more than this brief mention.

Mr. Skene also took a firm stand for the canalization of the Hudson river by the United States government. He joined forces with those who were advocating a 22-foot channel between the Barge canal and the ocean, this having been the time when the business organizations along the river formed the Hudson River Improvement Association in order to advance the interests of that project.

Mr. Skene continued the attempt of his predecessor to induce the Federal authorities to assume responsibility for canalizing the Hudson north of Troy. He even went to the length of printing in attractive form the report of the study made under Mr. Van Alstyne on this subject and presenting it to Congress in the form of a memorial. This study we have already reviewed. He also urged the Legislature to request the National government to improve both Lake Champlain at the northern terminus of the Champlain canal at Whitehall and the Oswego river at the northern terminus of the Oswego canal at Oswego. It happens that Federal waters adjoin the four main termini of the Barge canal system, these lying at Waterford, Whitehall, Oswego and Tonawanda. If improvements were not made at these four points by the time the new canal should be completed, then boats of enlarged size would be confined to the canal itself and the value of the deepened channel would virtually be nullified as long as the outlets of like dimensions were withheld. It can be seen then that the time was none too soon to begin agitation for this Federal coöperation. The Niagara at Tonawanda was already being improved under the United States engineers, but as we shall see, the other projects dragged along for years and finally the State had to step in and open a channel at one terminus in spite of the fact that it was working in Federal waters and was doing what in fairness the Federal government should have undertaken.

Although with 1909 there came another change in the office of State Engineer, Frank M. Williams entering upon the duties, in the matter of the channel between Troy and Waterford the new incumbent continued along the same line as his predecessors. But the time was growing short and so we find him urging upon the Legislature all speed lest the Champlain branch be completed before the southern outlet should be ready. Early in 1909 Superintendent of Public Works Stevens had been instrumental in securing a Federal appropriation for a survey of the Hudson, which was to determine whether the United States would assume this enterprise. It appeared probable that the engineers would report favorably and also Government officials seemed disposed to grant the desired aid, the chairman of the House Rivers and Harbors committee having assured representatives from the state the he would do all he could to induce the United States to undertake the work and complete it in time for Barge canal traffic, but the prospect for immediate action was doubtful and so Mr. Williams was urging haste. And this effort was not in vain. The Congress in session in 1909-10 made an appropriation for the work and on July 1, 1910, as soon as the funds became available, the army engineers, under the direction of Col. William M. Black, began work on the plans for a lock and dam at Troy. Credit for securing this aid from the Government belongs to several people and also to a number of organizations. Chief among them are the State officials and the chambers of commerce of Albany and Troy.

Among the pieces of work put under contract in 1908 were some that covered stretches of canal extending for twenty-two miles between South Greece and the Monroe-Orleans county line; also a section of canal at Little Falls including the lock of highest lift ever undertaken up to that time, and another section at Baldwinsville, together with the dam in the Oneida river at Caughdenoy, In addition contracts were awarded for building three more locks and movable dams of the bridge type in the Mohawk and for constructing the great reservoir on the headwaters of the Mohawk at Delta.

For several reasons the year 1909 is memorable in Barge canal history. The obtaining of Federal assistance in the Hudson is one reason. In this year also the Cayuga and Seneca branch was added to the enlarged system. A renewed and an aggressive agitation for this project began with the year and by means of a quick and intensive campaign legislative approval was secured during the current session and also popular authorization was achieved before the year had closed. But the outstanding reason for remembering 1909 is the terminal investigation begun in this year. Almost on a parity with the canal question itself stands that of adequate terminals, and the time of its inception, therefore, becomes a mile-stone in canal progress. But it is not necessary now to do more than mention either the new branch or the added terminals; each has already had its special chapter. Of the Hudson river scheme we shall hear again.

Because of interference arising from new construction the Superintendent of Public Works was having trouble in maintaining navigation on the canal, chiefly on the sections where the old and new alignments coincided. During the winter of 1908-09 more than forty culverts and other structures on the stretch between Rochester and Lockport were uncovered for the purpose of reconstruction or enlargement. Fearing that there would be leaks when the canal was refilled in the spring, the Superintendent set patrols, installed a temporary telephone line and at critical points stored supplies for making repairs. These precautions were wisely planned. Even before the canal was full leaks began to show at several of the structures and at a dozen or more of these the trouble proved so serious that the levels had to be emptied and the structures reinforced with a concrete covering. This experience resulted in adopting new methods for doing work of this character; also in a closer coöperation between the Superintendent and the State Engineer, the latter instructing his resident engineers not to allow a contractor to disturb any old structure which was essential to navigation until the Superintendent had been notified and had given his written permission.

It will be recalled that the Superintendent had recommended that the Oswego canal be closed while reconstruction was going on, since the maintenance of navigation on this branch was particularly difficult. In response the Legislature authorized him to close about half of it, the part between Three River Point and lock No. 10 at Fulton, during the whole season of 1909, and the remaining portion, that from Fulton to Lake Ontario, until the middle of July. By a law of 1910 permission was given to keep the southern half closed again for all of that year or to open any part of it from time to time as the Superintendent deemed best.

Publicity was given to two rival canal projects at about this time. On June 10, 1909, a Federal board of engineers reported to Congress on a proposed 14-foot canalization of the Mississippi from St. Louis to the Gulf, a scheme known as the Lakes-to Gulf project. This was estimated to cost $128,000,000 for construction and $6,000,000 annually for maintenance. The engineers reported that this scheme was not desirable. A few months earlier a Canadian report was made on the Georgian Bay Ship Canal, a proposed 22-foot channel between Georgian bay, an arm of Lake Huron, and the St. Lawrence at Montreal, estimated to cost $100,000,000,

In work put under contracts let in 1909 there were four which redounded much to the honor of State Engineer Williams. These were the contracts for canalizing the Mohawk from Rexford to Little Falls, well known among contractors at the time as the original Contract No. 20. In one form or another this work had been unsuccessfully submitted to bidders several times, beginning with October, 1907. In December, 1908, it had been offered for the last time in its entirety of nearly fifty-nine miles. The lowest bid at that time was $4,913,168.25, which was more than ten per cent above the engineer's estimate and consequently could not be accepted without formal approval by both the Canal Board and the State Engineer, but such approval was withheld. Because of earlier failures to receive acceptable bids the specifications under the offering of December, 1908, had provided for the acceptance of the finished work in eleven sections, the contractor thus not being required to maintain the whole length in a finished state until the entire contract should be completed. The plans were revised in 1909 by dividing the work into four parts. The aggregate of the four lowest bids on these parts was $4,690,546.90, a sum less than the 1908 bid by nearly a quarter of a million dollars. The elimination of the objectionable feature of accepting the work in eleven sections was perhaps of still more importance, since under the modified arrangement each contract had to be maintained in a completed state until it was accepted -- a marked advantage for the State.

A series of tests was carried on under State Engineer Williams in 1910 which was extremely important, but since the tests were of purely technical character little public comment was elicited. These tests were important to the engineer because they were in a field previously almost devoid of authoritative information, but they had a very practical purpose, their engineering value being entirely adventitious. They were of vital importance to the State because they were made in order to determine whether it was safe to build a certain proposed structure of somewhat remarkable design. In the event of failure of such structure the people of the state surely would have been aroused to the importance of tests which might have prevented so unfortunate an occurrence. Such was the real purpose of making these tests.

The tests had to do with construction at Medina, where, if the canal should avoid an objectionable loop, it was necessary to cross a deep gorge. After careful consideration of various types of steel and concrete aqueducts and also of a high embankment, it was decided that a concrete arch of single span, carrying a reinforced concrete trunk, was to be preferred. The length of span, center to center, would be 290 1/2 feet; the clear span, 285 feet, five feet longer than any concrete arch structure theretofore attempted and by far the longest single span arch aqueduct ever planned and one which would have to carry loads much in excess of those ever imposed on any similar long arch. The weight of water to be carried by the single span was 12,400 tons, the total load, including weight of structure, 46,000 tons. The width of the aqueduct was to be 129 feet.

By virtue of the length of span, the total width, the great load to be carried and the necessarily great cost, the proposed Medina aqueduct may properly considered the most important piece of concrete arch construction ever planned up to that time. It was deemed both advisable and necessary, therefore, not only to develop the design with the greatest care along the lines of the most approved theory of arch construction, but also to make a series of tests on concrete prisms and arch models for the purpose of obtaining additional information concerning the behavior of concrete under certain conditions of stress. Moreover, from reputable sources suggestions had been made that such an arch was in danger of failure through shearing on a vertical plane at or near the skew-back at a comparatively low resistance and long before the true compressive strength of concrete should be developed.

This series of tests, however, which was continued until there could be no reasonable doubt of the results, did not corroborate the theory in this suggestion, but showed conclusively that the arch would sustain its load in true arch fashion and that there was no danger of failure from so-called shear. Reports of the results of these tests were published in the Barge Canal Bulletin and the State Engineer's annual report and were copied by the engineering press of the country. It may be added that although these tests removed all fear that the structure as designed was defective, the aqueduct was not built. Instead the new canal follows the objectionable loop of the old canal. The reason for this was the character of the rock upon which the aqueduct must have been founded. It was a sandstone, known locally as "red horse," and doubt of its sustaining power caused the aqueduct plan to be abandoned.

In 1910 the first of the Barge canal locks was used for passing boats. This was the lock at Baldwinsville and the time of its first use was May 9. In order to be used the walls, gates and valves had to be completed, but operating machinery was still lacking. To supply the deficiency the gates were swung by means of block and tackle and horse-power, and the valves were raised by chain hoists. The lock chamber filled smoothly and its operation was entirely satisfactory. But the use of the lock at this time was not connected with regular canal traffic. The channel at Baldwinsville was so situated that it could not be used until adjoining long sections had been completed. The boats to pass the lock were part of the contractor's construction fleet. About a month earlier the gates, valves and power culvert of the lock at Comstock, on the Champlain branch, were operated, although no boat was present to be locked through. Traffic passed through this lock during the 1910 season, but conditions were such that temporarily one level was being maintained on both sides of the structure and so it was not for the time fulfilling any of the functions of a lock. On May 28, 1910, another new lock was brought into use and this was the first one to serve really as a lock in regular canal traffic. Additional interest attached to this structure because it was the siphon lock at Oswego, the first siphon lock to be built in America and the largest lock of the siphon type ever to have been built.

With the opening of navigation in 1910 there came into use the first of such new sections of canal as were being built along new locations. This was the northern portion of the Champlain branch, from Fort Ann to the Lake Champlain terminus at Whitehall. Work along this stretch had not been entirely completed, but it was so far advanced that the old canal between these limits could be abandoned and traffic could be turned into the new channel.

In 1910 the first of the Cayuga and Seneca contracts were awarded. These provided for dredging about seventeen miles of channel and for building the lock and dam at Cayuga. The number of contracts let during this year on the other canals was large, totalling more than a score, and the work covered by them included very nearly all parts of all three branches not already under contract. Almost all of the eastern half of the Erie canal was previously under construction and a section between Rome and Oneida lake added in 1910 virtually competed the contracts for building that portion. The work under eight of the contracts let this year lay in the western half of the Erie and after awarding these not many miles of the whole Erie branch were still unprovided for. Much of the remaining portions of both the Champlain and Oswego canals was also included in the contracts of the year. In addition the first two of the contracts for installing electrical operating machinery were let and also a contract for the great storage reservoir at Hinckley and another for the diverting channel to carry the waters from this reservoir to the point of need on the Rome summit level.

With 1911 there came another change in the State Engineer's office. Since the break in this instance was more marked than on former occasions, it is well to consider the general status of canal work at this time. This is given succinctly in the State Engineer's annual report for 1910, which reads as follows:

"At the end of 1910 about one-third of the work of construction on the whole canal is completed. There are under contract 422.2 miles of canal (including the Cayuga and Seneca), besides contracts for various electrical installations, bridges, dams and other structures, two great storage reservoirs and a feeder of nearly six miles leading from one of them. Of the remaining work, plans for 7 miles are completed, while those for 2.3 miles are at least three-quarters finished and those for 9.1 miles of canal and for the Glens Falls feeder are well under way. Thus it is seen that about 96 per cent of the canal mileage is under contract.

"With the exception of various minor structures, operating machinery and the like, there remains to be contracted for: Two sections of less than a half-mile each, one at either end of the Erie canal, a stretch of about two miles at Medina, the spur of seven miles to Syracuse, including five miles of lake navigation, the arm of 3 1/4 in the Genesee river, together with a dam, to form a harbor for Rochester, and some five and one-half miles of the Cayuga and Seneca canal. Thus, the Champlain and Oswego canals are under contract throughout their entire length, the extent of the Erie is broken only by a gap of two miles at Medina and by half-mile stretches at each end, and the 23 miles of the Cayuga and Seneca is three-quarters contracted for.

"The value of work under contract, at contract prices, or completed, amounts to $72,710,553, exclusive of the Cayuga and Seneca canal, and at the close of 1910, $25,869,723 has been earned on construction work. ...

"It was expected that 1910 would make a better showing than any of its predecessors and it did not fail in this respect. During the year construction work to the value of $9,578,408 has been done, and 107 miles of canal have been put under contract, besides the great storage reservoir at Hinckley and a feeder 5.75 miles long, to divert its waters to the Rome summit level.

"From the figures for former years ($330,120 in 1905, $711,490 in 1906, $2,216,300 in 1907, $5,443,303 in 1908 and $7,590,102 in 1909) a comparative view may be obtained. In the years 1909 and 1910, the period of my administration, the value of work done, $17,168,510 is seen to be twice as large as that for the whole period of work (four years) that went before. Also, studying the mileage table of contracts let (23.9 miles in 1905; 43.6 miles in 1906; 59.5 miles in 1907; 67.1 miles in 1908 and 121.1 miles in 1909) it may be seen that the miles of canal awarded during these two years of 1909 and 1910 is 54 per cent of all that under contract to the present time, or 52 per cent of the mileage of the whole undertaking.

"When the amount of work done in 1910 is considered, it must be remembered that many of the large contracts have been let so recently that actual construction has not yet started or has but just begun. Even on the great dredging contracts on the Mohawk river, that were awarded more than a year ago, the work has scarcely begun, so extensive plant installations being required that the machines are still in the trying out stage, before acceptance from the builders."

The period 1909-1910 marked the high tide of canal work so far as planning and putting work under contract was concerned. During these two years $39,594,432 worth of work, according to contract bids, was awarded.

Near the end of 1910 there came an inquiry into canal affairs by the Governor which demands our attention. The political situation of the day may have influenced the Governor in part in his action, for the campaign that autumn had been most stormy, but probably his own observations during a long public career had more to do with it. Governor White had but recently become the chief executive of the State. Upon the appointment of Governor Hughes to a place on the United States Supreme Court in October he had succeeded to the office of Governor. Governor White had been State Senator for many years and immediately afterward had been elected Lieutenant-Governor. As Senator he had known much about the canal and as Lieutenant-Governor he had been a member of the Canal Board. At a Chamber of Commerce dinner in New York on November 17, Governor White gave expression to his views on canal matters in a speech which attracted considerable attention. This he followed by addressing letters of common import to the State Engineer, the Superintendent of Public Works and the Advisory Board of Consulting Engineers, in which he said in part:

"After becoming Governor, this [the Barge canal project] seemed the most important subject before State government, and since then I have been giving it careful study and investigation. The complaints and criticisms received, and the information obtained convinced me that it was a public duty to call to the attention of the people of the State, not only to the progress of the work up to this time, but also to dangers and problems of the future, -- not so much in a spirit of criticism as in the hope that public attention might be fixed upon this great work and the most strenuous efforts be made to complete it expeditiously and in a way creditable to the State. ...

"I believe it is desirable that the people of the State shall have a complete and thorough knowledge of the conditions at this time, and that those in charge of the future conduct of the work may have the benefit of your information and experience.

"I, therefore, request a report from you covering, as fully as practicable, in the brief time remaining, the situation presented by the constitutional and statutory provisions, the character of the work up to this time, and such recommendations as you may see fit to offer."

Replies were receive from the two officials and from the board and in them the canal problems were discussed very freely. In reviewing these replies it is well to consider first the one from the Superintendent of Public Works, since his letter partakes largely of the nature of a criticism of the existing order, while the replies of the State Engineer and the Advisory Board contain a general defense of that order.

It will be recalled that in 1907 Superintendent Stevens criticised the State Engineer for the manner in which he had begun construction before the plans for the whole project had been completed. Mr. Stevens was now finishing a term of four years as Superintendent of Public Works. In company with the State Engineer and members of the Advisory Board the Superintendent had spent nearly two weeks in June, 1910 in visiting the various pieces of construction work. On the 15th he had made a report to Governor Hughes, criticising some of the work, and on the 25th the State Engineer had replied to these criticisms and had furnished to the Governor a detailed statement of the status of work upon the several canal contracts.

A reading of the Superintendent's reply gives one the impression that the whole official machinery charged with canal construction was fundamentally wrong and that as a result very slow progress was being made. The criticisms covered nearly the whole field of activities, but they were not constructive, the only definite suggestion for a change being one which was considered by many to possess very grave faults and which also would have occasioned much delay in carrying out. The Superintendent seems to have ignored the chief cause which had brought about the existing order of conducting canal work, namely, the failure of the method governing the 1895 enlargement.

There was much foundation in fact, however, for some of the criticism and people in general recognized this, but remedies which would not bring other troubles of as serious a nature did not seem to be at hand. The Superintendent decried the lack of continuity in responsible control, calling attention to the fact that a change had occurred every two years in the office of State Engineer. This complaint was only too true; there had been up to this time as frequent a swapping of horses in crossing the stream of canal construction as could naturally have happened. The Superintendent charged also that the State Engineer had too many other duties thrust upon him, that the salary was inadequate to the grade of service demanded and that he was detrimentally handicapped by not being allowed under civil service rules to secure such assistance as would be for the best interests of the State. The Superintendent also reiterated at length his belief in what he termed his make-haste-slowly policy, he deprecated the necessity of maintaining navigation during new construction, he complained that contracts had been allowed to drag along without applying the remedy of cancelation and reletting, he told of his requiring from the Advisory Board certificates of construction satisfactorily done, and he suggested as his solution for the difficulties a commission of three or five members, to have supreme and directing control.

State Engineer Williams in his reply acknowledged that the official machinery was somewhat unwieldy and did not always work as expeditiously as might be desired, but he said that on the other hand it possessed the advantage of putting a check upon each act of the State Engineer, the official in chief responsible charge, by three independent persons or bodies, thus minimizing the number of mistakes likely to be made inadvertently, although sacrificing something of speed. He believed it would be of considerable advantage to the project if some scheme could be worked out whereby there could be obtained a continuity of administration and some consolidation of authority and responsibility without at the same time losing the feeling of confidence inspired by the existing plan of control. He considered it impossible to put the work in the hands of a commission without amending the State Constitution, and said that a commission containing the State Engineer and the Superintendent of Public Works with their duties as then defined would have no real authority aside from these two officials and would be subject to a biennial change in its most important members. He agreed with the Governor in thinking it desirable that the people should have a complete knowledge of the progress of construction and said that to that end his department had issued a monthly publication, the Barge Canal Bulletin, which had been given wide circulation and had shown each month the exact status of the work and the money spent for it. He declared that as a rule contracts were progressing satisfactorily and moreover that as yet the State had not suffered by reason of the failure of any to make rapid speed, since uncompleted adjoining contracts prevented the use of these portions of the canal. Several times the State had annulled contracts because of slow progress and in each instance, if a new contract had been let, about a year had elapsed between the stopping and the starting of work. These experiences had taught that this method of hastening progress could not be looked upon with much favor. The State Engineer believed also that the whole work could be completed within the original appropriation, if it were pushed honestly and economically.

The reply of the Advisory Board was along somewhat the same lines as that of the State Engineer. The members said that they did not look upon the existing plan of administration as ideal but doubted if it could be improved under constitutional requirements. The really serious defect, they thought, arose from the frequent changes of the officials in control, and this condition would be almost fatal were it not for the provision in the Barge canal law for a continuing body -- the board of which they were members, which during the progress of the work had changed in its personnel in but minor part and very slowly at that. In view of past lessons and future prospects they deemed it undesirable to make any change in the administrative system, adding, "The Board believes that the present system while cumbersome in some respects does and will in its final result succeed in guarding the work and having it carried to completion in a good and economical manner and within the appropriation."

The autumn of 1910 witnessed a heated political campaign in New York state. Feeling ran high. Policies, measures and public acts were bitterly criticised and as stoutly defended. Among the matters thus attacked and upheld the Barge canal had a conspicuous place. The campaign ended in a political turnover, a sweeping change from the existing order in the executive, the administrative and the legislative branches of the State government. That work on the canal should reflect this upheaval was but natural.

When State Engineer Bensel entered upon his duties he found several things not to his liking. Among them was the slow progress by some of the contractors. In February he published a table showing the status of contracts. The text accompanying the table tells the story and we quote it:

"The accompanying table, now for the first time published in the Bulletin, sets forth more clearly than a lengthy description can tell it, the exact condition of contract work at the beginning of 1911.

"Analyzing this table, it may be said that the work covered by 9 contracts has been finished, 4 contracts have been terminated for one reason or another and 10 contracts were let so recently that the requirement for beginning operations was not in force at the beginning of the year. Of the 58 remaining contracts, 5 are for structural steel work and are somewhat dependent on the completion of structures under other contracts for opportunity of progressing; 6 are ahead of the percentage that should be done; some 5 are very nearly equal to this percentage, and 3 or 4 others are not far behind.

"This leaves 38 contracts, or nearly half the 81 let thus far, that are noticeably backward in progress. For some of the large contracts, awarded more recently and requiring extensive plant installations, there may be opportunity to increase speed and finish on time. But trouble may be looked for on the contracts that are much behind the schedule."

Another feature the new State Engineer objected to was the manner in which negotiations had been made with railroads for changing such of their bridges as crossed the new canal. We quote what he said in his annual report of 1911 concerning this matter and at the same time call attention to what was said about the same subject in the statement the State Engineer issued early in 1915, when he was speaking in regard to the condition of the Barge canal appropriation.

"At several locations along the line of the new Barge canal," said State Engineer Bensel, "the work of construction had been hampered and in some cases stopped by the fact that no negotiations had been consummated for the necessary rearrangement of the contracts along the railroads' right of way. Throughout the length of the Barge canal there are 86 separate crossings and in the majority of cases changes are necessary in the grade of the railroad and the requirements also necessitate new bridges being erected. Negotiations have been consummated for some of the most important of these crossings and the work where such negotiations have been completed is now under way by the railroad companies. Previous to the present year but little had been done in this regard and the nature of the work is both difficult and troublesome on account of the features which enter into the question of damage and the difficulty of maintaining the traffic while the work is in progress. During the past year six agreements have been consummated with the railroad companies and at eight other locations construction work has been started by the railroad companies and negotiations are at present pending at numerous other places and the progress of the canal work is but little hindered except at two localities which are now under way for settlement."

Another change of policy was that effected by the Canal Board in 1911 in reversing the action of its predecessor in regard to water leases at the Troy dam. This is a subject of which we shall hear later. Concerning its status in 1911 State Engineer Bensel said in his annual report:

"During the year 1910 action was taken by the previous Canal Board in an effort to cancel existing leases of the water not necessary for navigation purposes at the Troy dam. Early in the year discussion arose as to the right of the Canal Board to cancel in the manner which they did these existing leases on which depended the carrying on of certain portions of the work necessary for navigation at this locality by the United States Government. In accordance with the opinion of the Attorney-General the previous action by the Canal Board was not deemed proper and was rescinded. This brought about some discussion between the State authorities and the United States Government as to the building of the Troy dam, and while the questions at issue have not as yet been definitely decided it is hoped that in the near future the work of constructing the Troy dam may be undertaken by the State in such manner as was originally contemplated when the people voted the $101,000,000 for the improvement of the canal system, to extend from Congress street, Troy, to Buffalo, and thus preserve for the benefit of the people the water, which will be collected by the dam and which will not be needed for purposes of navigation. I am of the opinion that the State should construct this portion of the canal system in accordance with the vote of the people and thus secure the control and operation for the benefit of the people of not only the lock, which will be the throat or entrance to all of the State canal system, but also the water which will be available for power."

During 1911 a new design was made for the lock and dam at Scotia. Work had been started at this site in the latter part of 1908, but the contractors were not successful in unwatering the coffer-dam they had built, although attempts to do this had been made at various times until May, 1910. In August of that year the contractors had made application to be released from building these structures and had asked for reimbursement for alleged damages. The State had held that conditions here had not thus far proved more difficult than those successfully met in constructing dams on similar natural foundations in other rivers and that there was therefore no cause for annulling the contract or altering the plans. The new administration took a different view of the case and drew plans for building the foundations within pneumatic caissons.

Another problem to confront the engineers in 1911 was the method of strengthening the bridge superstructures at the movable dams in the Mohawk river. These bridges carry the movable parts of the dams and also the operating mechanism. Some little time before this it had become evident that the superstructures were too light, and the question now arose whether they should be strengthened simply so that they could operate as dams, as originally intended, or so that they might serve as highway bridges in addition.

An act of 1911 allowed parts of the Oswego canal again to be closed -- that between Three River Point and lock No. 11 at Fulton until July 31 and that between Three River Point and Lake Ontario from September 15 to the end of the season.

A break early in 1911 in the canal at Bushnell's Basin, near Rochester, where the channel is carried on a high embankment, called attention to the need of some means for guarding against similar accidents in this vicinity. The contract plans were altered so as to provide for conducting the canal over the embankment in a concrete trough.

In March, 1911, the first of the winches for operating the movable dams on the Mohawk river were delivered. These came to the Fort Plain dam and after certain preliminary work the gates were lowered into place against the concrete sill in the river bottom and the structure began to function as a dam.

So much of the whole canal line was under contract at the beginning of 1911 that we find but few new contracts let during the year and even these were of a minor character. The list contains three contracts for bridges, one for a guard-gate, two for transferring bodies from flooded areas to new cemetery sites and one for completing work in Fulton, which a former contractor had failed to do, thereby forfeiting his contract. But the year 1911 saw much work done on the contracts already in force, the increase being sixty per cent over that of the previous year and the total amount being equal to three-fifths of all that which had been accomplished during the six preceding years, the period of construction. The contracts found backward at the beginning of the year had advanced, so that at the close they averaged about 86 per cent of completion.

Channel in rock cut, near Rochester. The length of this rock cut is five miles. It reaches a maximum depth of 40 feet. The channel has a bottom width of 94 feet. In some places the sides were cut by channeling machines.

The outstanding event of 1912 was the beginning of work on the canal terminals. As soon as the official canvass of the vote on the referendum was made in December, 1911, State Engineer Benselhad appointed an engineer to take charge of the new undertaking and had begun to assemble for it an engineering organization which was distinct in large part from that engaged on the main project. While the terminal law described rather definitely the locations of most of the terminals, the exact locations were left for determination by the State Engineer and the Superintendent of Public Works, subject to the approval of the Canal Board. To gain the benefit of the opinions and desires of the people chiefly interested the State Engineer conducted several public hearings. That rapid progress was made in planning terminals is evidenced by the record, which is shown in the following quotation for the State Engineer's annual report. It should be explained that the fiscal year ended with September.

"To the end of the present fiscal year location plans for Barge canal terminals for the following localities have been approved by the Canal Board: Ithaca, Albany, Little Falls, Utica, Gowanus Bay (South Brooklyn), Schuylerville, Schenectady, Rome, Lockport, Mechanicville, Fonda, Fort Edward, Greenpoint (North Brooklyn), Amsterdam, Erie Basin (Buffalo), Herkimer, Ilion, Troy, Constantia, Syracuse, Cleveland, Watkins, Port of Call (New York city) and Dresden.

"Contracts have been entered into providing for the construction of terminals in the following localities: Ithaca, Albany, Little Falls, Mechanicville, Fort Edward, Schenectady and Herkimer.

"Plans have been completed for the terminals at Gowanus Bay, Whitehall, Fonda, Ilion, Amsterdam, Rome, Lockport and Utica, and partly completed for Troy and Syracuse."

On the morning of September 3, 1912, there occurred a serious break in the canal at Irondequoit creek. At this point the new canal coincided with the old and ran on top of a high embankment, widened for the purpose, the new channel being carried in a concrete trough, which had been built the year before. The break was occasioned apparently by the giving way of the culvert which carried Irondequoit creek under the embankment. This caused the trough to break and the escaping canal waters washed out about five hundred feet of embankment. So great was the length of the damaged portion that some persons familiar with repair work predicted that navigation could not be resumed during the season. But officials from the State Engineer's and Public Works departments were on the ground within a few hours and before the day had passed plans had been formulated and the organization of forces and the shipment of equipment and materials had begun, and within five weeks a new temporary channel was ready. In making repairs a concrete dam with an opening for the passage of boats was built at the end of each unimpaired section of canal and after the necessary filling had been made a wooden trough was constructed between these dams. The trough was 887 feet long, 22 feet wide inside and carried a seven-foot depth of water. It was supported by piles 25 to 35 feet long and driven to refusal in the embankment.

The State Engineer's report for 1912 contained a recommendation for the Legislature to take such action as was necessary to secure again for the State the work of constructing the lock and dam at Troy, in order that the State at the same time might regain jurisdiction over the dam and the potential water-power there available. Another recommendation urged on the Legislature the necessity of securing Federal coöperation without delay in the matter of improving the outlets at the several canal termini. The report also mentions the problem of railroad crossings and states that questions concerning financial responsibility at these crossings were being taken to the courts.

The publicity accorded to the Barge canal in 1912 calls for brief attention here, although the details of some of the events are given elsewhere in the volume. Canal exhibits were shown at six expositions, one each at Philadelphia and Pittsburg, Pa., New London, Conn., and Syracuse, and two at New York city, and at the three out-of-state places lectures were delivered. Papers were read at two waterways conventions -- that of the State association at Watertown and that of the National organization at Washington. Many lectures were given throughout the state, and two excursion parties, composed of eminent foreigners and each traveling by special train, made inspection trips over the length of the canal, accompanied by representatives of the State Engineer's department.

A fairly large number of canal contracts was awarded in 1912. Fourteen bridges were included, two of which were long structures of concrete arch type, across the Oswego river, the State in each case building the span over the canal and the town building the remaining portions. Five contracts were let for completing work where former contractors had failed and these embraced the southerly part of the Champlain canal, the redesigned lock and dam at Scotia, part of the stretch in Fulton and a section in the Seneca river near Mosquito Point. Work on the Cayuga and Seneca branch included the locks and dams at Seneca Falls and Waterloo and the spurs at the heads of both Cayuga and Seneca lakes, that at Watkins having been authorized by amendment to the original law. Then there were contracts for the Glens Falls feeder and the Onondaga lake outlet; one for electrical installation, another for a building at the Delta reservoir, and one or two more for minor details, such as clearing areas to be flooded and removing bodies to new cemeteries.

The closing of the Oswego canal authorized in 1912 included the portion between lock No. 11 at Fulton and Lake Ontario and extended from the beginning of the season to July 10.

In March, 1913, there occurred a flood of unprecedented proportion, which severely tested Barge canal construction. The high water was due to very unusual rains rather than to melting snow, and a wide area was affected, the flood that wrought such havoc at Dayton, Ohio, being caused by the same storm. The whole of the old Champlain canal and the eastern portion of the Erie, as far west as Little Falls, were completely under water. Embankments both old and new were washed away in several places, especially on the Champlain branch, but the new concrete structures escaped with almost no damage, in spite of the fact that they were forced to withstand strains which had never been anticipated. The Legislature, then in session, appropriated $75,000 for immediate repairs and these were made in time for the opening of navigation. A second appropriation, amounting to $200,000, was made for repairing damages to the Barge canal and this work was done later by contract.

The terminal contracts awarded in 1913 included those for Whitehall, Fonda, Ilion, Frankfort, Amsterdam, Fort Plain, Utica, Rome, Lockport, Port Henry and Plattsburg. Plans were prepared for terminals at Troy, Erie basin at Buffalo, Oswego and Watkins. Other sites approved by the Canal Board were Varick, Waterford, St. Johnsville, Cohoes and Ohio basin at Buffalo. All of the terminal contracts awarded thus far had provided for nothing more than dockwalls, terminal areas and harbor or approach channels. Warehouses and freight-handling devices were to be added and already studies for these essentials were being carefully made.

By the close of 1913 we find the State Engineer stating that 250 miles of completed canal were ready for use as soon as proper connections could be made with the existing canal. Among the completed structures aside from the locks were the movable dams in the Mohawk, the Delta reservoir and the dams at Vischer Ferry, Phoenix and Fulton.

In spite of former warnings that there was danger that the Federal government would not provide outlets at the canal termini by the time the canal should be completed there were two of these places, Whitehall and Oswego, where nothing beyond making investigations and reports had been accomplished. In the Niagara river the Government had done some work, but it was still to be decided how much it would do at Tonawanda. At Troy construction was progressing. It was very important that work at all these termini should be undertaken without more delay and so State Engineer Bensel in his 1913 annual report again and most earnestly urged the Legislature to give the subject careful attention and to memorialize Congress, setting forth the necessity for immediate action.

A law of 1913 authorized the Superintendent of Public Works to close such portions of the Oswego canal between Barge canal lock No. 2, at Fulton, and Lake Ontario during the year as in his judgment might result in expediting the work of construction.

Among the canal contracts awarded in 1913 was one for an important section of canal now for the first time put under contract. This was the channel at Medina. The elaborate tests made in 1910 on models of a concrete arch aqueduct will be recalled. The idea of carrying the canal over the gorge by aqueduct or otherwise was finally abandoned and instead it followed the old alignment through Medina, employing an exceptionally wide channel to compensate for lack of easy curves and requiring immense retaining walls where it circled the gorge. In the year's list were also two contracts for finishing work left uncompleted by former contractors, one a section near Utica and the other a portion at Mechanicville. Ten bridges were included, four of them being on the stretch between Syracuse and Oswego, three at villages in the western part of the state, one at Little Falls and another near by and one across the Seneca river at Howland island. Three contracts for electrical operating machinery were awarded and the remaining work to be let included a guard-gate near Crescent dam, steel sheet-piling at various places on the Rochester-Lockport level and the delivery of lumber and piles at Bushnell's basin.

Both 1912 and 1913 were years of large accomplishment in canal construction, just as 1911 had been and as 1914 too proved to be for that matter. These were the banner years of construction, the central period of activity, when nearly all parts were under contract and the great bulk of work had not yet been finished. In explaining why more was not done in 1913 the State Engineer said that one cause of delay was the litigation connected with the railroad crossings.

In 1914, just before long stretches of river canalization were about to be opened, we find canal officials considering a new feature of construction, that of aids to navigation, such as lights, buoys, lighthouses and the like. In the old canal the channel ran generally in land line, bordered on both sides by immediately adjacent banks; in the few river sections it hugged closely to the bank on which the towing-path was built. In channels of this character a navigator must have been grossly careless to run aground, but in the new canal, nearly three-quarters of which lay in canalized lakes or rivers, conditions were entirely different. Somewhere in the broad expanse of the lakes and rivers a comparatively narrow channel had been excavated and usually in the rivers there was not sufficient depth for navigation outside of this channel. It became imperative therefore to mark the limits of the channel carefully and in 1914 Superintendent of Public Works Peck carried on some experiments with lighted and spar buoys, endeavoring especially to devise a suitable type of light. The proper color scheme for lights and buoys also demanded considerable thought. The Federal government had adopted a rule that a certain color should be used on the right and certain other colors on the left side of a channel in proceeding upstream. As Federal waters adjoined the canal in several places it was expedient to conform to the Federal rule, but the difficulty arose that in doing this the colors would change sides while continuing in the same direction, since summit and depressed levels would be encountered alternately. The final decision was to regard the whole canal system as proceeding upstream in going away from tide-water, without respect to actual physical conditions. With this understanding a navigator on a trip away from the ocean finds red buoys and red lights on his right and black buoys and white lights on his left.

Two other features to occupy the Superintendent at this time were the method of making repairs to lock gates and a better means of protecting these gates than was provided by the buffer-beams. We find him recommending the purchase of portable cranes for handling damaged gates and also a type of protection like that used on the Panama canal, which is a chain that does not stop a boat abruptly, like a buffer-beam, but is paid out gradually by an automatic release until the boat comes to a stop.

In 1914 the Superintendent of Public Works was permitted by a legislative act of the same year to close such portions of the Oswego canal as he deemed expedient. The plan, practiced since 1909, of keeping the Oswego canal closed during a part at least of each navigation season doubtless hastened considerably the completion of the waterway, and in spite of this procedure the traffic did not seem to suffer.

Because of the political change which occurred in 1911 we examined closely the status of canal construction at that time. So now again, at the time of the next change in administration, we shall see how the record stands. State Engineer Bensel in his annual report for 1914 tells what had been accomplished thus far. Virtually all of the important structures except two near Rochester and a lock at Mays Point had been completed or were within a year of probable completion. Included in the list were the movable dams in the Mohawk river, eight in number, the fixed dams at Vischer Ferry and Crescent, the dams in the Oswego river at Oswego, Minetto, Fulton and Phoenix and in the Seneca at Baldwinsville, the movable dams at Cayuga and Waterloo, the fixed dam at Seneca Falls, the three dams in the Hudson river near Mechanicville, two of them fixed and one in part movable, the several locks and appertaining structures, and the two large storage reservoirs, that at Delta being completed while that at Hinckley was within five per cent of completion.

Mr. Bensel said that the Erie canal from Waterford to Three River Point and the Oswego canal thence to Oswego was so far advanced that by the spring of 1916 it should all be completed to Barge canal dimensions, this giving passage from the Hudson river to Lake Ontario. The Erie from Three River Point to the Montezuma aqueduct and also the connecting channel between Onondaga lake and the Seneca river were still farther advanced and should be finished by the spring of 1915. Between the aqueduct and Lyons there had been a delay on account of the existence of several railroad crossings. From Lyons to a point a little east of Rochester the canal was virtually completed except at the crossing of the Irondequoit creek, the place were the serious break occurred in 1912. From the point east of Rochester to a point about four miles west of the city, a distance of some eleven miles, canal work was about half done. Within this stretch eight railroad crossings were encountered and because adequate provision had not been made for these crossings in the original contracts, said Mr. Bensel, great delay in advancing construction work had resulted. From the point four miles west of Rochester to Tonawanda, approximately a hundred miles, the canal might be said to be entirely completed, the unfinished parts being small pieces of work which could not be done until immediately prior to the time of opening the whole new canal in that part of the state to navigation. At Tonawanda there was a short extent of canal to build before entrance into the Niagara river might be had, but it was considered that this section could be completed in a short time.

The northerly portion of the Champlain canal, from Lake Champlain at Whitehall to Northumberland, a stretch of thirty-five miles, had already been opened and used for navigation during the season of 1914. The remainder had reached such a stage, said Mr. Bensel, that it seemed probable that it would be so nearly completed by the spring of 1916 that traffic could be turned in, even though certain small sections might not have the full depth of twelve feet. The portion of the Cayuga and Seneca canal from its junction with the Erie branch to Cayuga lake and on through to Ithaca would be entirely completed by the spring of 1915. Work on the remainder, the section between Cayuga and Seneca lakes, was rapidly approaching completion and by the spring of 1916 should be ready for opening to navigation.

It would appear from this recital that most of the canal should have been put in operation in the spring of 1916, but it will be seen presently that the forecast was entirely too optimistic. It was only by almost superhuman effort that the canal throughout its whole extent was opened to navigation in the spring of 1918.

In this catalogue of accomplishments by the State Engineer there are one or two things which should have special attention. One is a discussion of what he called the northerly and the southerly routes in the vicinity of Lyons. He said that when he assumed office he found contracts in force for a line north of the railroads and that early in 1912 he made a thorough study of the situation with a view to a possible change of location. Finding, however, that if the change would be made at that time all that had been done theretofore would be wasted and also the State would subject itself to claims for loss by the contractor, he decided to continue along the line already begun. But in his opinion the other route would have been better, in that it eliminated several railroad crossings and also some of the crossings of the old canal alignment and moreover would have cost considerably less. Furthermore work upon the section would have been nearer completion.

Another subject is that of railroad crossings in general throughout the whole canal project. During all of Mr. Bensel's administration it was apparent that in the matter of railroad crossings he and also his associates on the Canal Board were not in accord with their predecessors. The early policy in regard to railroad crossings was one of the first things he criticised and to delays by reason of these crossings he attributed much of the lack of better progress during his administration. From a statement issued by the incoming State Engineer it will be seen presently that questions raised in 1911 as to the legality of former negotiations between the Canal Board and the railroads had thrown the matter into the courts, where after three years of litigation the original settlements were upheld. This decision was handed down by the Court of Appeals in 1914 and in his report of that year Mr. Bensel said that the extent of the State's liability having thus been determined the way was open to satisfactory agreements and also to putting an end to further delay. Throughout the whole period of construction the railroad crossing problem has been one of the most troublesome. It would seem that the stand taken in 1911 retarded rather than hastened operations.