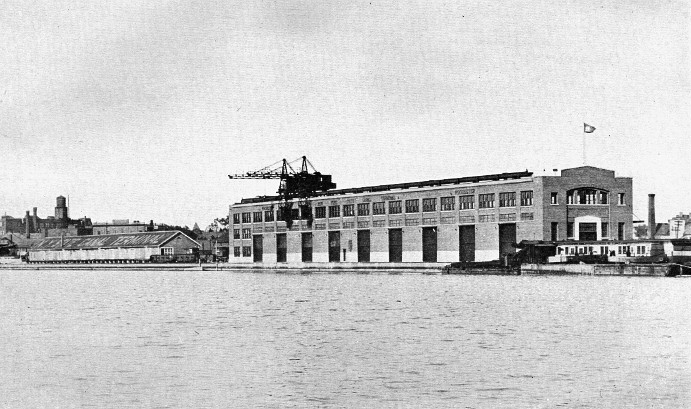

Example of terminal equipment. At Erie basin, Buffalo. Three kinds of machine for handling freight are seen -- capstans, three-ton cranes traveling on roof and pier rails, and in the far background a package conveyor.

Tardiness of Terminal Movement Strange -- Earlier Feeble Measures -- First Decisive Step, 1909 -- Broad Review of Terminal Question -- Properly Controlled Terminals Essential to Water Transportation -- Terminal Situations in Europe and America -- Relation Terminal Charge Bears to Carrying Charge -- Supreme Importance of Efficient Handling Machinery -- Task Set Barge Canal Terminal Commission -- Its Personnel -- Its Work -- Three Chief Terminal Investigations Almost Cotemporary -- Time Ripe for Terminal Improvement -- Essentials of Terminals -- Report of Terminal Commission: Preponderance of Local Traffic: Large Volume of Available Home Products Shown: Decline in Through Traffic Due to Terminal Lack: Refusal of Railroads to Coöperate a Large Contributing Cause: Greatest Terminal Need in New York City: Preëminence of the Port of New York: Almost Utter Lack of Canal Terminals in New York: Certain Observations in Europe: European Ports Visited: Estimated Cost of Barge Canal Terminals: Commission's Recommendations -- Terminals Authorized -- Localities Included -- Procedure in Construction -- List of Terminals Built -- Question of Hudson River Terminals Arises and Some Progress Made -- Appreciation of Need of Elevators Growing -- To the Fore in 1920 -- Elevators at Gowanus Bay and Oswego Authorized -- Arguments Advanced for Elevators by State Officials -- Details of the Two Elevators.

At the present time it seems almost incredible that it could have been eight years after the Barge canal was authorized before State-controlled terminals were added to the project. Indeed to those who have studied waterway problems and have followed canal terminal construction in New York state and who for years now have been thoroughly imbued with the idea that public terminals are an indispensable part of successful waterways, and also to a few others who have taken the pains to inform themselves on transportation topics, New York's long neglect of its canals in this respect has become a thing of surpassing wonderment. And yet it is not so many years since people began to realize that channels alone do not give transportation, or, as one writer puts it tersely and vividly, that waterways without terminals are as useless as electric wires without contacts. We can see now, however, that the State's neglect to furnish terminals was having its deleterious effect on traffic years before the Barge canal was projected. Still, New York, although it seemed slow to begin, did in reality take the lead among states in the matter of building and owning its waterway terminals. It is a fact also that at least a few of the leading advocates appreciated the need of terminals when the building of the Barge canal was being agitated, but they were biding their time, awaiting the suitable moment for launching the project.

But there have been those who long have known the importance of owning and controlling terminal facilities along our waterways. They are the people who have obtained possession of most of the water-front in seaport, lake harbor and river cities, and more often than not it has been the railroad interests that have thus obtained possession of these strategic sites.

Owning the terminals, these private and corporate interests have controlled the traffic and fixed the rates and generally their control has not been favorable to the waterways. The people at large, therefore, have not had a fair chance to know by experience the possibilities of economy in water-borne transportation, and the wonder is that they have been so long in awakening to the significance of their situation and in finding the effective cure for their commercial ills.

It was in 1909 that the Senate took its first decisive step towards providing terminals for its canals, but prior to that date it had from time to time attempted in a feeble way to prevent terminal extortions. In 1881 a Legislative committee had conducted an investigation on the subject of excessive charges and other abuses to which boatmen were subjected. Again, at the beginning of the nine-foot canal enlargement, State officials had urged the curbing of high terminal charges, in order that the full benefit of the improvement then in progress might be secured, the former season having seen many owners tying up their boats in preference to operating with such meager returns as prevailed. We have already learned what the New York Commerce Commission recommended in its report in 1900 -- that terminals be provided at Buffalo and New York and that terminal charges be restricted by law. In its first report to the Governor, in 1906, the Advisory Board of Consulting Engineers had mentioned in a somewhat incidental way the need of terminals at New York and at Tonawanda or Buffalo.

It will be observed, however, that up to this time no broad terminal policy for the whole state had even been suggested in any official utterance. The idea appeared a year or two later and probably it was of gradual growth. After the State Engineer and the Superintendent of Public Works had both recommended the measure twice in their annual reports and after canal advocates had done considerable work by way of agitation, the Legislature in 1909 (by chapter 438) created a commission, generally known as the Barge Canal Terminal Commission, to study the whole question of providing terminal facilities for the canals of the state.

Before we follow this Commission in its trips of inspection throughout the state or later in a visit to European ports, for the Legislature of 1910 authorized an examination of foreign harbors, we shall consider the general topic of waterway terminals. The work of this Commission was most admirable and the subject of its inquiry most momentous. In service to the State the Commission stands only second in importance to, if it does not equal, the State Committee on Canals, the body which was called upon to formulate for the State a canal policy. In like manner the Barge canal terminals are second only in importance to the canal itself. And so, to gain a full appreciation of the part terminals and terminal facilities play in both the broad scheme of water transportation and the narrower sphere of canals and navigable lakes and rivers, and to get a wide outlook over existing conditions and needs -- what has been done in a few places and what has not been done in a vast number of other places -- and thus to be able better to understand the supreme importance of the terminal problem in New York state, we need to pause and study briefly this general subject of waterway terminals.

In this study probably we can do no better than to read what a national commission had to say concerning the urgent need in the United States for adequate waterway terminals, and what is more important, the proper control of such terminals. This commission spoke with authority. It had had ample opportunity to learn the situation both at home and abroad. This was the United States National Waterways Commission, a body composed of twelve members of Congress, seven senators and five representatives, Senator Theodore E. Burton of Ohio being chairman. This commission was a contemporary of the Barge Canal Terminal Commission, having been created by act of Congress only about two months earlier but making its final report about a year later than the New York commission. We quote at some length from this final report. 1

"Undoubtedly the most essential requirement for the preservation and advancement of water transportation is the establishment of adequate terminals properly controlled. Under present conditions the advantage of cheaper transportation which the waterways afford is largely nullified by the lack of such terminals.

"According to the report of the Commissioner of Corporations on water terminals, private interests control nearly all the available water front in this country, not only at the various seaports but also along the Great Lakes and the principal rivers. Only two ports in the United States, New Orleans and San Francisco, have established a public control of terminals at all comparable with the municipal supervision existing at most European ports.

"The above-mentioned report on water terminals also shows that a large proportion of the most available water frontage is owned or controlled by railway corporations. Through this ownership or control they practically dominate the terminal situation at most of our ports, and they have generally exercised their control in a manner adverse to water traffic. In many cases they hold large tracts of undeveloped frontage which they refuse to sell or lease, and which are needed for the construction of public docks. This railway control of terminals is one of the most serious obstacles to the development of water transportation, for the control of the terminal means practically the control of the route. An independent boat line has small chance of success where it is denied the use of docks and terminal facilities or is required to pay unreasonable charges for their use. The high terminal charges at many of our ports make it impossible for small boat lines to enter at all.

"The commission believes that the proper solution of this terminal question is most vital to the future of water transportation. It is, however, more a local or State than a Federal problem. As pointed out in the preliminary report of the commission, there should be a proper division between the functions of the Federal Government and local communities in the improvement of waterways. The Federal Government should improve channels, while the municipalities should coöperate to the extent of providing adequate docks and terminals. It is absolutely essential for the growth of water transportation that every port, whether located on the seacoast or on some inland waterway, should have adequate public terminals, at which all boat lines can find accommodations at reasonable rates. Inasmuch as the indifference of communities to their responsibilities in this matter largely nullifies the benefits of expenditures by the Federal Government for channel improvements, the commission emphasizes the recommendation made in its preliminary report that further improvements in rivers and harbors be not made unless sufficient assurance is given that proper wharves, terminals, and other necessary adjuncts to navigation shall be furnished by municipal or private enterprise, and that the charges for their use shall be reasonable. It can not be too strongly urged that in many cases it is not the condition of the channels so much as it is the lack of terminals that is retarding the development of water transportation.

"Where water frontage necessary for the establishment of public terminals is held undeveloped by railway or other private interests, a special act of the legislature should be passed, empowering State or municipal officials to condemn the property for public use. This plan has already been followed in a few cases and should be more widely adopted. The proposal has sometimes been made that the Federal Government should condemn private property and establish public terminals along the rivers and in the harbors which it is improving in order that the benefits of such expenditures may not be nullified. The commission, however, would not recommend the adoption of such a policy unless it shall be found after a fair trial that the States and localities can not adequately solve the problem."

We may gain a good understanding of what the terminal situation in Europe and America was at that time, and it has not changed much since, by referring to an excellent article on the subject in a book entitled American Inland Waterways, by Herbert Quick, published at about the same time the two commissions were doing their work. From a chapter in this volume, headed "Terminals a Vital but Neglected Matter," we desire to select a number of outstanding facts. We shall quote the author verbatim in part and in part we shall give the substance but not the exact words. Also we shall add a few facts gleaned elsewhere. The chief original sources of information on terminals, it may be said parenthetically, are the reports of the three commissions we shall mention presently. This article reveals a broad outlook and a keen appreciation of the whole terminal field and the presentation of the subject is so lucid and convincing that the Barge Canal Terminal Commission reprinted the chapter in its entirety as an appendix to its final report.

It must be remembered that Europe led America by several years in caring for its terminal needs. Mr. Quick displays for our view the contrasting situations on the two continents. He shows that as a rule the municipalities of Europe built, owned and controlled their terminals. Antwerp, a city of fewer inhabitants than San Francisco and with only a few more than New Orleans, was the greatest port in Europe and second only to New York in the world. Her warehouses, railway tracks and all transshipment facilities were owned and administered by the city and had drawn to her wharves the shipping of the world. She had spent $45,000,000 and was spending $55,000,000 more.

Hamburg had no natural advantages. Situated sixty miles up the Elbe, with mud and tide to contend with, by the spending of $100,000,000 she had made her terminals so attractive that her commerce was growing faster than that of any city, save New York and Antwerp, and had already equalled that of London.

The docks at Liverpool were administered by a board so constituted that the interests of ship owners and shippers were considered rather than that of profits in docks. Situated on an estuary, with a difference of thirty-one feet between tides, having shifting sand bars and silt at its mouth, still this port had been built up by its own efforts alone, with no local or imperial taxation and had become one of the greatest in the world.

Rotterdam is another city that had won success by making her harbor a municipal monopoly. She had spent $30,000,000, but not a dollar was furnished by the general Holland government.

After struggling for eighteen years to get control of her harbor, Havre succeeded in 1900 and began improvements. The growth of her commerce since 1900 had been astonishing. Plans under way contemplated spending $17,000,000 in addition to the $42,000,000 theretofore spent in making a harbor in an estuary with a tidal range of twenty-five feet and a bottom of shifting sand.

Other cities were mentioned, such as Manchester, Bristol, Glasgow and Newcastle, but this list will suffice. At London the story was somewhat different. Though still the greatest port in Great Britain, London had fallen behind New York, Antwerp and Hamburg and her antiquated port administration had often been charged with blame for this decline. She was seeking a reform, but the interest she must pay on the $200,000,000 valuation of her docks showed the result of allowing them to fall into private hands.

Turning to America, the picture is not so attractive. New York was preëminently first in commerce, for several reasons, but it is doubtful whether she could have reached her present height if she had not freed herself from private ownership of terminals. As it is, she has a very perplexing problem to find suitable new frontage for public docks for her wonderful traffic.

At Philadelphia and Boston, the other two cities one would naturally expect to be the great ports on the Atlantic coast, conditions were all against water-borne traffic. Philadelphia owned some twenty docks, but most of them had less than nine feet of water. In theory all her docks were open to the public, but practically they were controlled by private ownership. Boston owned no water-front except a few scattered landings of little importance. Nearly all the docks at Detroit were private property. So were the wharves of Providence -- a city well situated for commerce. Duluth owned but a few ferry landings. The water-front at Washington belonged to the United States but was leased to private parties. The largest artificial harbor in the world is at Buffalo, but the frontage was practically all under private control. Chicago, with possibilities of becoming the greatest of lake ports, had almost no public docks and owned no frontage suitable for building them, and her facilities for handling freight were so poor that it was not unusual for boats to carry to Milwaukee goods consigned to Chicago and there ship to destination by rail. New Orleans and San Francisco were the two exceptions to the rule. They alone had instituted public control of terminals, somewhat after the manner of European cities. Montreal was the exception among Canadian ports. Out of fifty of the foremost United States ports, only two, New Orleans and San Francisco, have practically complete public ownership and control of their active water frontage; eight have a small degree of control, and forty none at all.

Another essential feature in the solution of transportation problems is generally passed over lightly, as being simply a part of the terminal facilities. It is indeed a part of the facilities, but how important a part will appear from a little study. Before actual transportation begins and after it ends it is necessary to load the goods and then unload them. This is the terminal charge, as the actual haulage is the carrying charge. No data are available to determine this terminal charge exactly. A well-known Chicago engineer, however, with a corps of assistants, has spent a year investigating the subject for commercial interests in Chicago. While his study was not completed and the calculations cannot be relied upon as accurate, they are thought by most freight experts to be approximately correct. They point to the conclusion that on the average railway shipment in this country the terminal expense is equal to 250 miles of haulage and that the terminal charge for the average water shipment would be equivalent to about 2,500 miles of carriage.

These figures need no words to emphasize the fact that the lack of mechanical devices at terminals accounts for the decadence of our waterways or to point out a field worthy of the best trained technical men in the country.

The voyage from Chicago to Buffalo is less than a thousand miles. In a water shipment between these points the actual carriage would be about one-third and the terminal charge two-thirds of the cost. It is this two-thirds that offers opportunity for reduction. The installation of docks and apparatus has in many instances cut the handling costs more than in half. This has been done in the ore, coal and wheat shipments on the Great Lakes. While the terminal charge on miscellaneous freight from Duluth to Cleveland is thought to be about twice the carrying charge, the efficient handling machinery for wheat, ore and coal so reduced the terminal charge that just about equals the carrying charge.

If, with these effective devices, half the cost of shipping coal from Cleveland to Duluth consists in loading and unloading, what can be said of the practice on the Mississippi? At St. Louis and Memphis negroes still load the river boats by carrying packages on their heads and reaching the boat by a narrow gang plank. At Vicksburg the only landing is a quagmire of mud.

Quoting Mr. Quick with reference to freight-handling devices, "Where waterways are effectively used, here and abroad, the proper physical equipment of the terminals is taken for granted as an essential element in the business. The handling devices for the grain, ore and coal trades on the Great Lakes are among the commercial wonders of the world; especially the splendid achievement in freight handling by which ore is brought about a thousand miles from Duluth to Pittsburg, -- loaded on ships, carried to a terminal on Lake Erie, transshipped to cars, and unloaded at the furnaces at a cost that makes it possible for our steel producers to command the markets of the world. But we have signally failed to solve the problems of handling miscellaneous and package freight on rivers and canals. Water traffic has been decadent because of the hopelessness of its contest with unregulated railway competition; and a decadent industry is apt to give up at all points. But in the new era which we hope for, the commercial interests must adjust themselves to waterway methods of to-day at the best American and European ports, and not to those of the days when Mark Twain piloted the floating palaces on the Mississippi -- floating palaces built for passengers and show, and not for the cutting off of the last fraction of a mill in the cost of taking a ton of freight from the bank, carrying it to its destination, and discharging it. ...

Example of terminal equipment. At Erie basin, Buffalo. Three kinds of machine for handling freight are seen -- capstans, three-ton cranes traveling on roof and pier rails, and in the far background a package conveyor.

"We have seen how daring is the enterprise of the great foreign ports in the matter of investments in docks, harbor improvements,dredging operations, and the like, and how independent the cities are of the general governments. It is quite as instructive to observe how complete is their realization of the necessity for efficient physical equipment for freight handling. Our river cities may well copy these merits. With few exceptions our interior towns that importune the government for the deepening of channels seem destitute of any ideas as to the duties resting on themselves. If the Ohio river towns had done as much for themselves as the government has done for them, every village would have its public dock, every dock would have its warehouse, and every warehouse would have its machinery for transshipment, loading and unloading. The harbor manager would be a greater man than the mayor. The finances of the town would be to the extent of the taxing power at the service of the port. Money would be poured out for better boats than the antiquated craft now plying the river. Every hull would be capable of being thrown open from the top, and cranes capable of doing the work of the uncertain gangs of roustabouts at a fraction of the present expense would handle freight more cheaply that it is handled in the average railway freight house. The railway tracks would be taken out over the water on aerial structures where necessary, and the expensive draying up and down steep levees would be eliminated. At the more important points specialized appliances would be installed, and the town with ambitions toward real cityhood would retain the best engineers for the designing of terminals, to be its proudest achievement, and its greatest municipal undertaking.

"Along all our rivers, lakes and canals the best brains in the technical world must in the future be engaged on the problems of saving this half or two thirds of the expense of transportation which is involved in handling and rehandling of freight. ... From the public docks the huge packages will be swung by great cranes from the open holds of boats to the cars, and from cars to boats. As an example of the devices sometimes adopted to save time and the breaking of bulk, the methods of sending American meats into London may be cited. They are unloaded from the ships directly into delivery wagons at Southampton, the loaded delivery wagons are carried on cars to London, ready for the horses which haul them to the butchers' shops. In many places trains of cars are carried on boats across rivers and straits, and long distances by water. There seems to be no reason why grain, live stock, cotton, and much heavy freight which is costly to unload, and which must make a part of its trip to market by rail, should not be carried on boats in the cars -- the original shipping packages. Neither does there seem any reason why huge boxes each containing a carload should not be made capable of being swung from the boat to the flat-car to which it might be fitted, and back to the boat again when necessary. The cranes capable of doing the work are already invented, and in use."

The deplorable conditions existing in marine traffic through lack of handling machinery is seen when it is known that the terminal costs at New York and Liverpool exceed the hauling costs of the 3,000-mile voyage. The following picture of the marine situation is illuminating:

"The human worker still reigns practically supreme on the docks in all his primitive wastefulness. ... He rolls up an annual payroll of millions; he congests traffic by his complex and cumbersome motions. He strikes when he pleases and ties up whole harbors. ...

"Half the commerce of the nation comes through the Narrows and is distributed from the wharves and piers in the vicinity of Greater New York. It comes in leviathans, but is seized upon by an army of human ants who spread themselves over the docks in a maze of inefficient and costly motion. ...

"In view of the immense volume of freight loaded and unloaded by ... vessels every day, the paucity of handling facilities, viewed from the standpoint of modern business management, is almost incomprehensible." 2

After this brief review of the general terminal question we can follow with clearer vision the efforts of New York State to rid itself of an incubus which in the past had worked havoc but which under changing modern conditions threatened utter ruin to the canal system unless it should be removed.

The act which nominated the Barge Canal Terminal Commission was written on liberal lines. The needs of the whole state were included in its scope and after the amendment of the following year little was omitted which might conspire to a full understanding of the whole subject. The task set the Commission was this -- to quote the language of the law: "It shall be the duty of said commission to visit and inspect the various harbors in this state connected with the canals, as well as all harbors in this state where freight carried on the canals may be either received or discharged. It shall also be the duty of said commission to report to the legislature at the earliest possible date, in detail its findings and its recommendations as to the harbors and canal termini, where, in its judgment, special facilities for receiving or discharging canal freight should be provided; as to available sites for such terminal structures; as to the amount of land necessary to be taken at each point for such purposes; also as to the character, extent and probable cost of construction and maintenance of each of such terminal structures; the revenues, if any possible to be derived therefrom; also generally as to matters that, to the commission, may seem pertinent to the subject."

Four State officials were named as constituting this Commission, the four men who would be supposed by virtue of their office to have the welfare of the canals most at heart. These were the State Engineer, Frank. M. Williams, the Superintendent of Public Works, Frederick C. Stevens, the chairman of the Advisory Board of Consulting Engineers, Edward A. Bond, and the Special Examiner and Appraiser of Canal Lands, Harvey J. Donaldson. At its first meeting the Commission elected Mr. Williams chairman and at a later meeting it appointed Alexander R. Smith to the position of secretary. Charles S. Sterling served as engineer to the Commission at first but later he was superseded by Charles Kiehm. Two of these men had been members of important former commissions, Mr. Bond (at that time State Engineer) of the Committee on Canals, and Mr. Smith of the New York Commerce Commission. It will be remembered that the Committee on Canals was appointed by Governor Roosevelt in 1899, after the failure of the nine-million project, to study the whole canal question and recommend a State policy, and that the Commerce Commission was named by Governor Black in 1898 to inquire into the causes of the decline and the means for revival of the commerce of New York.

The Commission attacked its arduous task with vigor and zest. It visited the cities and towns along the canal and also along its connecting natural waterways, both to see existing conditions and to discover the needs. It held many public hearings and the meeting places for these hearings were well scattered along the whole line of the waterways. It accumulated a vast amount of pertinent data and in this phase of the work it was generously aided of course by those who were promoting the claims of their particular localities. The work was too extensive to be finished in the single year allotted and so the Legislature of 1910 added another year and at the same time made provision for the commissioners to visit Europe and there continue their studies.

The Commission complied with the full mandate of the law and its final report contained not only the required estimates but also plans so carefully worked out that they served as a substantial basis for contract plans after the building of the terminals had been ordered by the State. Its report in fact was so complete and embodied so much of value on the whole study of terminals, both home and foreign, that it at once took a high place among the books of its class. If the term may be applied to technical subjects, it is scarcely stretching a point to call it a classic on waterway terminals. We shall turn to a somewhat detailed study of this report in a moment.

There was one phase of the terminal question, however, -- that of grain elevators -- which the Commission little more than touched upon. This was not due to a lack of appreciation of the importance of elevators but rather to want of time to give the subject as thorough investigation as it deserved, and so the Commission had to content itself with recommending further investigation. When we come in proper sequence to look into this subject we shall see how very important a part of New York canals adequate elevators are. The reason for this condition is that the canals through New York state are, according to the claims of their friends, the rational outlet to the great grain belt of North America, a belt having an area of a million and a quarter square miles, a population of thirty millions of people and a production of five billion bushels annually.

The three chief American reports on water terminals appeared at about the same time and in rapid succession. In 1910 a volume on the subject was published as the last of three volumes covering an exhaustive study of transportation by water in the United States, made under Herbert Knox Smith, United States Commissioner of Corporations, of the Department of Commerce and Labor. This third volume was devoted to the subject of terminals. Then in 1911 the final report of the Barge Canal Terminal Commission appeared, following a brief preliminary report of 1910. In 1912 the United States National Waterways Commission made its final report. We have already quoted from this work. It too followed a preliminary report, submitted early in 1910.

Obviously the time was ripe for the New York Commission to do its work and for terminal advocates to attain their end. The enlarging of canals had been in progress now for several years and if terminals were to be added their commencement could not be delayed much longer without danger of not having them finished when the channel should be ready for navigation. On the other hand, to have begun them much sooner would not have been wise. The people had voted an immense sum for improving their canals and seemingly they were in complaisant mood for completing the job thoroughly. Waterway agitation was rife throughout the eastern and middle states. The report of the Terminal Commission, when it came, contained illuminating data in abundance and its arguments for terminals were evidently convincing. But aside from this report, for most of the people of the state never saw it, there appeared to be abroad among a majority of the folk at least a meager appreciation of that which had become so obvious in Europe as to need no argument and which was gradually but surely gaining credence here, namely, that canals of necessity must have adequate and publicly-controlled terminal facilities. Doubtless the researches of the three National or State commissions, operating directly or through magazine articles and press editorials which they induced, were responsible for this molding of public opinion. When the question came to popular vote on the New York canals there was no strenuous contest, such as the days of 1903 had witnessed. It seemed almost as if the friends of the canals were so sure of victory that they deemed it of little importance to bestir themselves. It is noteworthy, moreover, that of several referenda submitted to the people in 1911 that for canal terminals was the only one to receive approval.

But we have not yet stopped to inquire what a canal terminal is. The varying conditions of different kinds of traffic introduce many minor factors which go to make up satisfactory terminals, but in general there are only a few fundamental requirements for all waterway terminals. The Commissioner of Corporations in his report gave this number as four and even one of these might on occasion have to be dispensed with. We may well adopt his classification. These four essentials are: (a) Good wharves, (b) warehouses and storage facilities, (c) mechanical appliances for the handling or transshipping of freight, and (d) -- that which is highly important though not always practicable -- belt-line railway connections with adjacent railroads and industrial concerns, so as to coördinate water with rail transportation and with local production and distribution. Sufficient depth of water of course is also necessary, but this is a feature of the channel rather than the terminal problem.

We are not now making an exhaustive study of the terminal question and so we need not delve too deeply into the wealth of material contained in the Terminal Commission's report, but there are a few statements in it, aside from the estimates and recommendations, which we should know; they illumine both the terminal and the general canal problems. We shall mention them before we give the estimates and recommendations.

A study which the Commission made of existing and past canal traffic showed that the local freight being carried on the State canals was several times as great as the amount of through freight. Also that for a long period, at least forty years, the annual tonnage of local freight had remained almost a fixed quantity, while the through freight had dropped to one-fifth of what it was forty years earlier and only one-sixth of what it was thirty years earlier. Both of these facts were rather surprising in the light of popular belief. Somehow the people of the state had come to regard the canal as of little local value and moreover of use chiefly to carry cargoes which simply passed through the state from lakes to ocean. This revelation of both the preponderance and the stability of local traffic was well calculated to cheer the citizens of the state and also it proclaimed the need for terminals at the various inland canal towns.

There was a further study, moreover, which disclosed facts that might measurable fortify whatever feeling of satisfaction the people had. This was a study to ascertain how many tons of commodities suitable for canal traffic were produced in the mills and factories of the towns which were situated on the Barge canal. In making this compilation only such products were included as were generally carried in bulk and for which rapidity of passage was not an important factor. A total of a little more than ten and a half million tons was shown, valued at well over two hundred million dollars.

We recall that the law authorizing the canal had fixed its carrying capacity by stipulating that the supply of water for the Erie branch should be sufficient for at least ten million tons annually. By a strange coincidence this study showed that there were produced, virtually upon the canal banks, this very amount of commodities which properly should be shipped by canal. The people of the state thus had it in their power to become themselves the recipients of the full beneficence originally planned for the canal, without leaving room for outsiders to enjoy the State's generosity. The total capacity of the canal, however, it may be added, is actually close to twenty million tons. The facts revealed by this study may have had some weight in deciding the popular vote on the terminals, but doubtless they have been forgotten long since by most persons, for those most intimately concerned have not yet made large use of the completed canal.

The decline in the amount of freight carried on the canals was well known, but that this falling off was entirely in the through freight was a fact that perhaps had not been fully realized until this study was made by the Terminal Commission. The decline was attributed by the Commission largely to the lack of independent terminal facilities at Buffalo and New York and to the increasing control by the railroads of terminals not only at Buffalo but also throughout the Great Lakes region. A contributing cause was one which we have not yet mentioned but which has been responsible for much of the failure of waterways to get their due share of traffic. This was the refusal by railroads to prorate on through routes where freight would naturally go part way by rail and part way by water. This of course is but a piece of the generally hostile attitude railroads have assumed toward all canals and canal boat lines not their own. In 1917 the New York Legislature enacted a law aimed at the correction of this condition -- an act to regulate joint rail and water routes.

This subject of the relationship between railroads and waterways contains many phases besides the one just mentioned and is a most important topic, but we shall leave the full discussion for a later chapter. We may just add a sentence or two. Speaking of the refusal of railroads to prorate with water carriers, the National Waterways Commission says, "In many cases the route, which apparently is the natural one, would be by water for three-fourths or more of this distance, yet the charge for the remaining railway haul is so considerable as to render carriage for the longer haul by water unprofitable." Viewing the subject from a slightly different angle, the Terminal Commission says, "The railroads have always refused to either prorate or through-rate with canal carriers but, on the contrary, have only been willing to receive freight brought to them by canal boats in the most unusual and expensive manner, such as by forcing them to discharge their freight at places other than railroad wharves, and then team it to the railroad wharves, instead of allowing them to come directly to the railroad wharves, and there discharge their freight. By refusing, on the other hand, to deliver freight to canal boats at their wharves, they have been able to prevent them from carrying large quantities of freight that would otherwise have been shipped by the canals."

In amplification of the first explanation we mentioned for the falling off of through freight, namely, the lack of terminal facilities at Buffalo and New York, the Terminal Commission says:

"This subject of terminals was considered at some length by the New York State Commerce Commission, in its report made to the Legislature on January 25, 1900, and all that that Commission then said may be as aptly repeated at this time as then.

"Upon the suggestion of Governor Roosevelt, the members of that Commission went to Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis and Duluth, and there interviewed the larger shippers, particularly those who shipped flour and packing house products east, and the statements made by these western merchants is most illuminating as to the reasons why such commodities are no longer shipped for export via the port of New York, the chief reason advanced being that there were no places in Buffalo affording independent terminal facilities. We quote from the statements of that State Commission of eleven years ago, in part, as follows:

" 'Agents of the great flour mills, who ship annually millions of barrels of flour to Europe, who appeared before this Commission in New York, and the officials of the mills in Minneapolis and in Duluth all united in the statement that lack of canal terminal facilities for package freight alone prevents flour coming to New York by way of the canal, which is now sent to the outports.'

"Again we quote from the report of the New York Commerce Commission:

" 'Agents of the great provision merchants of Chicago have also made clear to this commission their inability to use the canal for their business because of the lack of canal terminals.' "

When the Terminal Commission came to make its recommendations, much stress was laid on the need of adequate facilities at New York city. Why this metropolitan district was entitled to so much consideration and why so large a share of the appropriation eventually fell to its lot, we may understand perhaps by listening to what the Commission has to say relative to the volume, the growth and the importance of traffic in the port of New York and also the insufficiency of its facilities for handling that traffic. Precise information on the volume was not available but several trustworthy estimates had been made and these did not differ widely. The Commission was confident that at least half of all water-borne traffic of the United States centered in this harbor, and the total tonnage of the nation, as reported in a Federal document which had been prepared with great care from the almost unlimited official data was 256,000,000 tons per annum.

Speaking of the growth of foreign commerce in the port of New York, the Commission states that between 1880 and 1898 there was no increase, and then, after mentioning the succeeding rapid increase and the relatively small increase in wharfage accommodations, pertinently asks the question, "If, at the end of a period of stagnation in the growth of New York's foreign commerce, extending over eighteen years, there was such a serious lack of sufficient wharfage as to force steamship lines to other ports to secure the accommodations they required, as testified by the president of the dock board in 1899, what can the condition be now, twelve years later, when there has been an increase of 87 per cent in the foreign commerce of the port, as well as a very large increase in the coastwise and local traffic besides? With but 23 per cent of increased wharfage during that period, inclusive of the very large and costly works to which we have referred above, manifestly the congestion of traffic along the most desirable and most useful waterfront in the city of New York must at the present time be acute, and extremely ominous."

The port of New York, in its foreign trade, its coastwise trade and its local harbor traffic, stands without a rival in America. But greater still, it outranks all other ports of the world in the volume and the value of its commerce. Several things have conspired to this end -- its priceless and ample natural harbor, its admirable arrangement of land areas surrounded and divided by deep water channels, its preëminence as the metropolis of the western hemisphere, and more than all, perhaps, its situation at the outlet of Nature's gateway to a vast interior, a gateway through the only practicable route in United States territory for a waterway and the best route for a railway from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic coast, a sort of "Northwest Passage" to the heart of the continent.

We remember in this connection that the original Erie canal had much to do with making New York the chief American port in the early days and thus in giving it an initial upward trend which enabled it to continue in its success and to retain its proud estate. Moreover, we recall that before the canal was built New York had not been the first port of the land, that before that time it had even been among the more backward of the colonial ports.

It is when New York is compared with other ports of the United States that its glory is brightest, its preëminence most conspicuous, its claim to leadership unapproachable. But on the other hand, if it were to retain its lead in the world and keep ahead of its great rivals in Europe, the need for better facilities and a larger growth could not be neglected.

New York is not well situated for any general railroad occupancy; its insularity precludes that. But this very isolation, aided by favorable configuration between various parts of the greater city, is a boon to water-borne traffic. If the New Jersey shore opposite New York city is considered as a part of the port of New York, then there is in this port a total water frontage on rivers, bay, sound and ocean of 444 miles. But until recent years there has been no inclination to regard this as a single port. Political boundaries have held taut; the two States have each had their separate methods and machinery of control and the result has been contention and hostility. Nature made this one incomparable port; man has striven to defeat the intent of Nature. But this old-time stupidity is now passing and it seems probable the present efforts for harmonious, united control will soon be in such complete working order as to carry out some comprehensive and already partially perfected plans for improvements that will increase abundantly the facilities so sorely needed. This is a subject by itself, however, and considerably later in occurrence than the terminal agitation. It should not be injected into the present discussion. In due time we shall recur to it.

We have been considering general traffic conditions in the New York harbor. The whole picture of inadequate facilities is cheerless enough, but when we turn to view the accommodations afforded to canal shipping it becomes so dark as to be utterly doleful, and the wonder grows that the canals could have continued even to do any business whatsoever against such overpowering odds. To quote the Terminal Commission: "In New York city there has never been any section of the improved waterfront, not even at the so-called canal basins, or canal districts, where there were any facilities, other than the unshedded wharves, for the accommodation of freight destined for shipment over the canals, or for freight received from the canals. There has, even at such open wharves, been no one to receive and care for any freight that might be received either for shipment over the canals, or that might be received at them by canal boats for local use. Lacking these essentials to the modern handling and carriage of freight it was inevitable that the through business should have almost vanished."

The Commission goes on to cite a single exception to this condition. In the case of certain commodities which could not bear railroad rates the agents for the railroads would contract for shipping this freight as far as Buffalo by canal, and thus there came into existence what, in the parlance of the canal world, were known as "canal lines." These were not lines at all, but were individually-owned boats, chartered intermittently by the railroads. As canal boats had to be sufficiently loaded to pass under the bridges, owners were usually glad to charter their craft and generally the railroad agents were able to drive a hard bargain on west-bound cargoes. But boats had then become few and these canal lines, once the fictitious property of the railroads, had almost disappeared.

New York city's neglect of canal interests and its disposition to do as little as possible for the accommodation of canal shipping were notorious. Indeed, so pronounced were they that it would seem that the city deserved but little consideration from the State in the matter of terminals. By legislative direction two places on Manhattan had been reserved in part for the benefit of canal boats, but these places were without sheds or other facilities and only so much had been done by the city as was necessary to conform to the mere letter rather than the spirit of the law. But this attitude of intentional neglect was chargeable to former city administrations, which had regarded the water-front almost wholly as a means for increasing municipal revenues, rather than to the public in general and moreover this attitude was changing. Because of this former maladministration, however, the Terminal Commission advised that any terminals erected by the State in the city of New York should not be put under the control of the city authorities.

If New York city had been at fault in neglecting canal accommodations, the other cities and towns of the state had done little better. In none of them had there been even a semblance of a policy or system adopted for the improvement or development of its water-front. On the contrary these municipalities had permitted private interests -- chiefly railroads -- to acquire the choicest water-front properties, much to the embarrassment of water carriers and in no degree helpful to the promotion of water-borne commerce.

What the Terminal Commission said concerning the relationship existing between railroads and waterways in Europe is worth noting. In all countries except Great Britain and southern France there seemed to be a general and complete interchange of freight between rail and water lines, transfers being made directly between cars and barges, at a minimum of expense and a maximum of speed. The result of this fair dealing between the two systems showed conclusively that the railroads were quite as great beneficiaries of such relations as were the water routes. The railroads were not compelled to spend their money in roadbeds and equipment for handling great quantities of heavy, low-grade, low-priced materials, which paid but little in freight charges, but could devote their equipment and their development to accommodating the higher-priced commodities, that paid better rates, and to transporting passengers, thus being able to pay large dividends on the capital invested.

Another noteworthy observation made by the Commission while in Europe was that there prevailed in those countries a belief, seemingly everywhere accepted as sound, that in waterways complete efficiency was the chief objective and expense a secondary consideration, also that the general mood and the material advancement of State and city were immeasurably more to be sought after than direct financial returns sufficient to replace the moneys expended, and that these indirect benefits were so substantial as fully to justify a continuance of improvements and an enlargement of facilities, although the money sunk in them might never be directly returned to the states and municipalities advancing it. Indeed, it was seen that at many harbors the authorities did not expect to recover all that was expended annually even in maintenance and administration, contenting themselves with the indirect and satisfying benefits following in the wake of cheap transportation.

In connection with this thought we desire to emulate the Terminal Commission in calling attention to New York State's generous canal policy, which is in exact accord with the advanced ideas reached in Europe after many years of experience. In 1882, after more than sixty years of canal tolls, which had actually returned to the public treasury several millions more than the canals had cost in building and maintenance, the State opened its waterways free for the use of all without tolls or dues of any kind. And within two years after the tolls had been abolished the State commenced enlarging its canal locks and this was but the beginning of a series of improvements which have continued virtually to the present day and which have been gigantic beyond even the dream of anything that had gone before. And in all of these enormous expenditures since 1882 there has been no possibility of direct return. If would seem that in this willingness to spend their millions, which will be repaid only in the coin of general welfare, we can read nothing other than the belief of the people of the state in their canals. And this belief has been attested repeatedly. First the canals were freed from tolls by an overwhelming majority; at each succeeding improvement authority for new expenditures has been voted without stint; on several occasions, and always by large majorities, the Constitutional dictum has been reaffirmed that the canals shall not be sold but "shall remain the property of the State and under its management forever." Evidently the people, whenever they are required to think deeply on the subject, deem their canals a mighty force in their hands and consider that they may use this force for controlling rates and bettering transportation, greatly to the benefit of all and for the advancement of the public good.

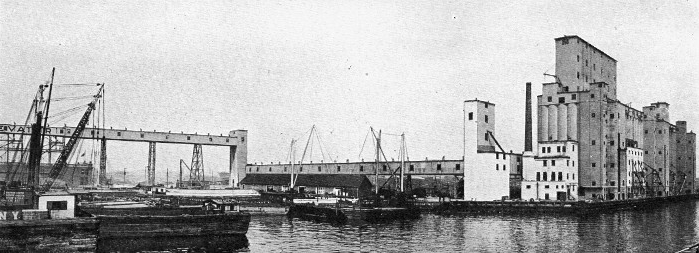

Terminal at Rochester. Two freight-houses are shown, a substantial brick structure, 400 feet by 50 feet in size, and a much smaller frame house. The two cranes are two-ton electric traveling roof cranes of trolley type.

Before giving the recommendations of the Terminal Commission we desire to pause long enough to enumerate the ports inspected in Europe by the commissioners. They visited Great Britain, France, Belgium, Holland and Germany. Their report contains a painstaking general study of terminal conditions and growth of traffic in each of the countries and also detailed descriptions, often accompanied by maps, of the principal ports. All but one or two of these ports they visited in person and the list includes London, Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Goole and Glasgow in Great Britain; Rouen and Paris in France; Brussels and Antwerp in Belgium; Amsterdam and Rotterdam in Holland, and Cologne, Düsseldorf, Duisburg-Ruhrort, Dortmund, Mannheim, Strassburg, Kehl, Frankfort-on-Main, Berlin, Hamburg, Bremen, Kosel and Breslau in Germany.

In its final report the Terminal Commission recommended that the State appropriate sixteen and a half million dollars for constructing and equipping public terminals for the Barge canal. The cities it designated as the places for such terminals were Buffalo, the Tonawandas, Rochester, Syracuse, Oswego, Utica, Schenectady, Whitehall, Troy (two terminals), Albany and New York. For New York thirteen terminals were advised, at the following sites: Spuyten Duyvil, West 135th street, West 78th street, West 51st to 54th streets, Gansevoort street, Vestry street, Canal basin on East river, Grand street, Sherman creek, Mott Haven, East 136th street, Newtown creek and Gowanus bay. The commission had studied the particular needs at each of these places and had made plans to suit the requirements for each proposed terminal. In its recommendations the number and length of piers or dockwalls, the amount of land required, the size of storehouse, the kind of freight-handling machinery and other like details of construction were named and an estimate of cost given, but these particulars do not concern us except to show the minute care with which the investigation was carried out. The total of the estimates submitted for the cost of each terminal was $16,408,315[? ... original text has "$166,408,315", which is ten times the appropriation mentioned in the first sentence of this paragraph]. This included an item of $600,000 for terminals at the smaller cities and towns, not specifically named. The estimate of annual expense for maintaining all of these terminals was $120,413.

The commission made fifteen further recommendations, all of which were important and had a more or less direct bearing on several phases of the terminal and general canal problems of the state.

These were succinctly put and we quote the words of the report as follows:

"1. Plans for terminal structures should be prepared by the State Engineer and Surveyor and their construction carried out under his direction when such plans have the approval of the Canal Board.

"2. The terminals should be administered under the direction of the State Superintendent of Public Works.

"3. Charges for use of terminal facilities should be fixed by schedule established by the authority having the terminals in charge, when approved by the Canal Board.

"4. The Federal Government should be urged to undertake the straightening of the Harlem Ship canal at the Johnson Iron works at the earliest possible moment. The State, the city of New York and the borough of the Bronx should co-operate in securing the necessary right of way.

"5. The Federal Government should be urged to improve the Bronx kills to a depth of at least 15 feet at mean low tide.

"6. The city of New York should clear the unnecessary obstruction to navigation in the Harlem river by removing from the channel the piers of High bridge.

"7. The State should retain title to all its lands under water and to all canal lands except as it may advantageously exchange for other lands better adapted for canal or terminal purposes. Any private occupation of State-owned lands should be by lease for a definite term, except such as border directly upon the canals, in which case leases should be revokable at the pleasure of the Superintendent of Public Works. Private occupation of State-owned lands should yield a reasonable revenue to the State.

"8. The title to all water power created incidental to the construction of the Barge canal should be held by the State and such power leased for terms of reasonable length.

"9. Legislative authority should be given to each municipality located on a lake or river to control the development of its water-front by reasonable regulations regarding the erection of bulkheads, piers and other structures.

"10. The city of New York should reconvey to the State a section of the land under water in Jamaica bay for terminal purposes to be selected when the improvement of the bay makes it available.

"11. The State Engineer should be directed to make an accurate survey of the suggested canal to connect Jamaica and Flushing bays, and the necessary appropriation for the expense thereof should be made.

"12. The bridges yet to be built in connection with Barge canal construction on the Oswego and Seneca rivers between Lake Ontario and Onondaga lake should be so constructed as to be readily convertible without unnecessary expense from a fixed to a movable type.

"13. A commission composed of representatives of the leading commercial organizations in different parts of the State should investigate conditions affecting interchange of freight, the subject of prorating and through-rating, the recognition of through bills of lading and of low through-rates at points of interchange, as between water and rail carriers, also the relation of grain elevators, fixed and floating, to rail and water carriers, in this State.

"14. The Legislature should direct the Attorney-General to participate in behalf of the State in the proceedings before the Interstate Commerce Commission for the abolition of the differential on freight from Chicago to New York and vice versa.

"15. Some competent authority should be designated to make a study of the various types of barges with a view of recommending that type which is best suited to the enlarged canals." 3

There was no long interim between the presentation of this report and the carrying out of its main recommendation. The report was transmitted on March 1, 1911, and before the session of the Legislature which received it came to an end an act had been passed authorizing the construction of canal terminals. Response to some of the minor recommendations was incorporated in the terminal act but others were not so quick to receive attention. We shall see later how the State eventually paid heed to some of the latter class, how a board of conference was named to devise means for promoting the projects which involved the straightening of the Harlem at the Johnson iron works, the deepening of the Bronx kills and the removal of obstructions at High bridge, how the State Engineer was directed to survey the Jamaica-Flushing route, how adjustment of the relationships between rail and water carriers was attempted by legislative act, how provision was made for building some of the needed grain elevators and how a commission on Barge canal operation was instructed to report on the type of boat best suited to navigate the new canal. The discussion of these subjects will come in due course. We have anticipated the action on the Oswego canal bridge problem and already have described the result of this recommendation.

With the filing of this report the Terminal Commission went out of existence. There had been a political turnover in State administrative affairs at the beginning of 1911 and two members of the Commission, Mr. Williams and Mr. Stevens, had been superseded by new incumbents in their respective offices of State Engineer and Superintendent of Public Works. But the pushing of terminal agitation was taken up by canal advocates. At the call of State Waterways Association officials, representatives assembled at Albany from the leading municipalities throughout the state at what was termed a Barge Canal Terminal Conference and the result was the drafting of a bill and its introduction in the Legislature. Numerous towns which had not been mentioned specifically in the Commission's recommendations grasped their opportunity and secured their inclusion in the drafted bill, some of them having employed engineers meantime to prepare tentative plans and estimates.

The act carried an appropriation of $19,800,000 and so, of course, by reason of the constitutional inhibition to vote more than one million dollars without approval by the people at a general election, it became a referendum in the fall of 1911. No very marked opposition to the measure arose and there was no especially aggressive campaign in its favor. In general public sentiment seemed to accept as sound the argument that inasmuch as a vast sum was being spent to modernize the canals it was well to increase the amount by the few other millions needed to make the original expenditure completely effective. But the small majority in its favor, only 4,416 and the large degree of apathy (more than half a million blank votes) taught canal advocates to bestir themselves when their next proposition came before the people.

Before we consider what the terminal act authorized and also in order that we may know just what things were to be provided under the law, it may be well to see how the act defined the word terminal, what it presumed to include in this rather broad term. Section one of the law reads, "The words 'terminal' and 'terminals' as used in this act shall mean and include lands, docks, dock walls, bulkheads, wharves, piers, slips, basins, harbors, structures, tracks, facilities and equipment for loading and unloading and temporarily storing freight transported upon the Barge canals of this state."

The law stipulated definitely where the terminals should be built and fixed with considerable detail the character and the extent of construction at each locality. It also set apart a given sum which might be expended in building each terminal. The places specified in the act included Erie basin and Ohio basin at Buffalo, North Tonawanda, Tonawanda, Rochester, Lyons, Syracuse, Oswego, Utica, Rome, Troy (two sites), Albany and fourteen localities in New York city, as follows: Port of Call near Dyckman street, West 135th street, West 78th street, West 53rd street, Gansevoort street, Vestry street, Piers 5 and 6 on East river, Piers 4 and 7 on East river, Broome and Grand streets, Sherman creek, 150th street on Harlem river, East 136th street, Newtown creek and Gowanus bay. At each of the prospective terminals the details of construction and the amount of money to be spent were set forth in the act, except that the allotment for New York city was named as a lump sum. The law further provided terminals for Lockport, Herkimer, Little Falls, Fort Plain, Canajoharie, Schenectady, Rouses Point, Port Henry, Plattsburg, Whitehall and Mechanicville and appropriated a certain amount of money for each, but it did not specify any details of plan. Then it contained another list, which included Amsterdam, Fultonville, Clyde, Palatine Bridge, Port Gibson, St. Johnsville, Constantia, Waterloo, Newark, Palmyra, Fairport, Ilion, Spencerport, Brockport, Holley, Albion, Frankfort, Medina, Cohoes, Waterford, Fort Edward, Seneca Falls, Ithaca, and Geneva, at which places terminals might be built if certain conditions as to filing petitions by local officials and citizens were complied with and if thereafter certain designated canal officials upon due investigation were in favor of granting the petitions. Inclusion on this last list really availed these particular localities nothing, however, since the same privilege of petition was accorded any other place for which no specific terminal provision was made in the law. One other terminal location was mentioned -- Jamaica bay -- but nothing was to be done here until the Legislature should make special appropriation for the work.

In matters of general procedure the law made substantially the same provisions as those under which the canal was being built. As we have seen in our former study the Barge canal act contained a few rather bold innovations as to the manner of awarding contracts and prosecuting contract work. These had been found to work well and were repeated in the terminal law. The Canal Board, as in general canal affairs, was the supreme governing body. The State Engineer was to make the plans and supervise the construction. The Superintendent of Public Works was to operate and maintain the terminals after their completion. The making of rules and regulations to govern the use of the terminals devolved upon the Canal Board.

The framers of the law foresaw the danger of individuals or corporations trying to monopolize the terminals and therefore careful provision was made to prevent the success of any such attempt. The use of the terminals was to be restricted to such reasonable time as was necessary for the transshipment of goods and any privilege of occupancy was at any and all times to be revokable by the Canal Board. As specifically stated in the law the terminals were to remain the property of the State and be under its management and control forever. The law in this particular reads as follows:

"The terminals provided for in this act when constructed shall be and remain the property of the State, and all of said terminals, including docks, locks, dams, bridges and machinery, shall be operated by it and shall remain under its management and control forever. None of such terminals or any part of such terminals shall be sold, leased, or otherwise disposed of, nor shall they be neglected or allowed to fall into decay or disuse, but they shall be maintained for, and they shall not for any purpose whatsoever be in any manner or degree diverted from the uses for which they are by this act created."

In choosing sites and making plans for terminals the State Engineer was granted liberal discretion by the law. His general policy of construction was first to provide two things -- the necessary depth of water in harbor or slips and the terminal land area with its accompanying dockwall and piers. These he followed with warehouses, paving, tracks and the like, and finally he added freight-handling machinery. The wisdom of this order and also of a certain deliberateness of procedure, which has characterized the whole terminal work, will be obvious on a little thought. New sections of completed channel were being opened for navigation every year and by following this policy there were appearing along with these sections terminals which, though perhaps lacking storehouse and handling facilities, were still available for use. Also as the canal came into greater general use there was opportunity to learn by experience what kind of traffic was being developed at the several localities. This knowledge was essential, for the records of the old canal gave little indication of what might be expected of the new canal, and the kind of traffic, of course, would determine what type of machinery should be provided.

We do not propose to follow now the course of terminal construction, but an enumeration of all the terminals which have been built seems in order at the present time. In the first of the following two lists there are mentioned fifty-six localities. These are the places where terminals have been built with money appropriated by the terminal law, although at a few of them vertical walls built in channel construction were utilized for terminal dockwalls. This list contains terminals of various kinds, all the way from the elaborate creations in New York harbor, where immense sheds on long piers are crowded daily with goods which are handled by the latest type of electrically-operated device or even where a two-million-bushel grain elevator with all its intricate parts is being erected, to the simple structure at some small hamlet where the whole equipment consists of nothing more than a wall at which boats may land, a leveled area back of it and a humble frame storehouse, and even the storehouse may sometimes be lacking. With but one or two exceptions, where work has been halted for some reason, this list enumerates the places where efficient terminals have now been built.

Arranged in topographic order, beginning at the Lake Erie end, the list runs as follows: Buffalo (Ohio basin), Buffalo (Erie basin), Tonawanda, North Tonawanda, Lockport (upper terminal), Lockport (lower terminal), Middleport, Medina, Albion, Holley, Brockport, Spencerport, Rochester, Newark, Lyons, Ithaca, Weedsport, Syracuse, Oswego (river terminal), Oswego (lake terminal), Constantia, Cleveland, Rome, Utica, Frankfort, Ilion, Herkimer, Little Falls, St. Johnsville, Fort Plain, Canajoharie, Fonda, Amsterdam, Schenectady, Crescent, Cohoes, Troy (upper terminal), Troy (lower terminal), Albany, Mechanicville, Schuylerville, Thomson, Fort Edward, Whitehall, Port Henry, Plattsburg, Rouses Point and the following in New York: West 53rd street, Pier 5 (East river), Pier 6 (East river), Gowanus bay, Greenpoint, Long Island City, Hallets Cove, Mott Haven and Flushing.

The second list contains eight names. These are the places where terminals exist by virtue of walls built under the Barge canal act, none of the terminal funds having been devoted to them. They are Pittsford, Fairport, Palmyra, Seneca Falls, Baldwinsville, Fulton, Brewerton and Waterford. The whole number of terminals, it thus appears, is sixty-four. Few towns of size along the canal are without some terminal facilities.

The adding of terminals to the canal project had been delayed so long after the beginning of the canal itself that speed in the new venture was essential. Accordingly, as soon as the result of the official canvass of votes was known, on December 13, 1911, State Engineer Bensel appointed an engineer to take general charge of this work. The appointee was John A. O'Connor, who was elevated from the position of Division Engineer of the Eastern division, and his new title was Terminal Engineer.

Speed was made also in the beginning the work of construction. By August of the following year the first contracts were awarded and before the year closed terminal work at Ithaca, Albany, Little Falls, Mechanicville, Whitehall, Fort Edward, Schenectady, Herkimer, Fonda, Ilion, Amsterdam, Rome and Lockport was under contract. Location plans for a dozen more terminals had received the Canal Board's approval and the work of preparing plans for them was under way or in some cases was completed. It had been found advisable to study local needs quite carefully before beginning the preparation of plans. The State Engineer conducted hearings at towns where terminals were to be built and through these consultations he got the local points of view concerning both the best sites and the existing and prospective traffic requirements. As we have seen, the terminal act in a broad sense fixed the locations and described the character of construction, but exact sites and definite details were left to later determinations. The State Engineer and the Superintendent of Public Works decided as to sites, their decision being subject to the approval of the Canal Board. The contract plans were worked out with careful study in the State Engineer's department and then were submitted to the Canal Board for approval.

In his annual report for 1912 the State Engineer called attention to the omission of an important section of the state from participation in the terminal project. No cities or villages on the Hudson river between Albany and New York had been included. To be sure the Hudson river below Albany had never been looked upon by either officials or the public as really a part of the State waterway system, but there was no logical reason for this view and under the new order, wherein the larger portions of the old-time canals were themselves river canalizations, the last vestige of reason for excluding the Hudson river from the State system was gone. Then too New York was a Hudson river city and it had received a very generous portion, almost half in fact, of the terminal allotment. The State Engineer did well therefore in suggesting that this omission be righted.

Since this particular part of our study has to do chiefly with the account of terminal agitation and authorization rather than the record of construction, we may with propriety at the present juncture follow the fortunes of these canal terminals for Hudson river towns. Although the State Engineer had made his suggestion in 1912, it was 1918 before the Legislature took the first step in response. In his report for 1915, State Engineer Williams, in discussing the question of finances in connection with terminal construction, said that at certain places the development contemplated by the act could be accomplished for less than the amounts set apart for those places and recommended legislative action to permit the using of these balances for other terminals and in his opinion some of the cities along the Hudson might well be chosen for this purpose. The Legislature of 1918 (by chapter 555) ordered the construction of canal terminals at four Hudson river cities, Poughkeepsie, Kingston, Newburgh and Yonkers, but aside from a sum for making surveys and plans it provided funds simply for the purchase of necessary sites. Surveys of the lands were made without delay and within about a year titles had been acquired by the State. Then the State Engineer proceeded to make studies and preliminary plans, but further money has not been forthcoming and there the matter has rested, except that each year State Engineer Williams has reminded the Legislature that in effect the State has pledged itself to the construction of these four terminals and the time was at hand for the fulfillment of that pledge. But in the disturbed financial conditions and in the business depression throughout both the state and the nation subsequent to the World war there may found ample reason for failure to appropriate moneys for this and all other projects which are not absolutely essential. Petitions have been received for terminals at three other Hudson river cities, Beacon, Hudson and Rensselaer, and preliminary studies have been made for the sites of such terminals. Mr. Williams has recommended that the Legislature include these places also in whatever appropriations are made for terminals along the Hudson.

There has been a strong organization, it should be added, working for these river terminals. This is known as the Hudson Valley Federation and it comprises an aggregation of allied commercial organizations from Troy to Yonkers, numbering ten thousand in their membership. This federation had been back of the 1918 legislation. At first $950,000 had been asked for, a sum supposedly sufficient for both acquiring the sites and constructing the four terminals. At a hearing before the legislative reference committee it was suggested that, because of war exigencies and other demands for State funds, the amount be cut to $160,000, of which ten thousand should be for surveys and plans and the remainder for securing the sites. This was agreed to and the measure was passed. In 1919 a bill appropriating $350,000 to begin construction went through the Legislature but was vetoed by the Governor on the ground that it should be provided for by bond issue. But this procedure was the very thing the advocates of the project had tried to avoid, having kept even their original request below the million-dollar constitutional limitation.

When the Terminal Commission made its report it included among its list of recommendations one that a commission composed of representatives of leading commercial organizations of the state be appointed to investigate certain conditions, one of them being the relations between elevators, fixed and floating, and the rail and water carriers. Such a commission has not been appointed, but the end in view has been attained in another way.

The Terminal Commission had not included the subject of elevators among its investigations because, as it reported, there had not been time to study properly this phase of the terminal question. But those who have had to do with the building of our canal terminals came to see, and as time passed the conviction grew stronger, that one of the most pressing needs of the day was that of grain-handling facilities, and also that eventually the State must include elevators in its waterway scheme if the canals were to get anything like their proportionate share of what should be, in the nature of things, their chief article of freight.